On the 15th of January in 1790, nine mutineers from HMS Bounty, 18 people from Tahiti and one baby arrived on Pitcairn Island—one of the most isolated habitable places on the planet. Surrounded by the southern Pacific Ocean and with hundreds of miles of open water between it and the nearest other islands, Pitcairn is the epitome of solitude.

Before the Bounty escapees showed up, the island may not have seen human occupation of any kind since the 1400s, when it was still inhabited by Polynesians. That community perhaps existed for centuries—centuries that seem to have culminated with a depletion of natural resources, as well as conflicts on other, distant islands that cut off lines of trade and supply, leading to the effective extinction of Pitcairn’s human occupants. What was, at least superficially, a habitable place had become unsustainable, until the arrival of the Bounty on that fateful day in 1790. Remarkably, it took another 18 years for any other ship to drop anchor at Pitcairn, even though the settlers recorded sightings of vessels passing in the distance.

The story of Pitcairn is just one extreme example of the unusual dynamics of human occupation across the southern Pacific. Within the regions of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia, there are tens of thousands of islands scattered across millions of square miles of ocean. Many are barely more than a protuberance of rock and coral, and even the habitable spots are not all inhabited at any given time. But taken together, they represent a vast landscape of potential settlement and civilization for people motivated to navigate across Earth’s watery depths.

The parallels between this unmistakably terrestrial environment and our cosmic surroundings are striking. In the Milky Way galaxy, there are perhaps as many as 300 billion stars. The best estimates from exoplanet-hunting efforts, such as those undertaken with NASA’s Kepler space telescope, suggest that within this ocean of stellar bodies there may be more than 10 billion small, rocky worlds in orbital configurations conducive to temperate surface conditions. Like the islands of Earth, these exoplanetary specks might both generate and support living systems and could provide a network of waypoints for any species determined to migrate across interstellar space. And that is where things get really interesting.

Just as Western Europeans eventually realized that the peoples of the southern Pacific had spread across its thousands of miles of ocean on simple vessels gliding along at just a few knots, we can now see that spreading across our galaxy need not require much more than persistence and a modest amount of cosmic time.

Most famously, over a lunch in 1950 with fellow scientists, physicist Enrico Fermi first recognized this fact and—as the story goes—blurted out, “Don’t you ever wonder where everybody is?” The “everybody” in this case was any spacefaring species, and the question developed over time into the equally famous, albeit somewhat mislabeled, Fermi paradox: unless technologically proficient species are vanishingly rare, they should have spread practically everywhere across the galaxy by now, yet we see no evidence for them. Fermi, renowned for his ability to carry out so-called back-of-the-envelope calculations in his head, had figured out in approximate terms that the Milky Way could be settled in the blink of a cosmic eye when each tick of the galactic clock accounts for millions of years.

In 1975 astrophysicist Michael Hart produced the first properly quantitative and nuanced study of this idea, in which he put forward what has become known as Hart’s “fact A.” This refers to the absence of aliens on Earth today. That unassailable fact (for most level-headed people) led Hart to the conclusion that no other technological civilizations currently exist—or have ever existed—in our galaxy. The key to this assertion, much as with Fermi’s original insight, lies in the relatively short amount of time it would apparently take for a species to spread across the Milky Way’s 100,000-light-year girth even using modest, far-slower-than-light propulsion systems.

Physicist Frank Tipler also studied the problem, and he reported on his work in 1980, demonstrating, much like Hart, that in a few million years suitably motivated aliens could indeed visit everywhere. Given that our solar system has been around for 4.5 billion years and that the Milky Way assembled at least 10 billion years ago, there has been more than enough time for species to wind up on all inhabitable worlds.

Critically, though, these investigations considered the spread of life somewhat differently. Hart assumed a process of settlement “in the flesh” by a biological species, whereas Tipler imagined star-hopping swarms of self-replicating machine probes that would spread without restraint. In most settlement scenarios, the stellar systems and their planets become inhabited, if they were not already, and then serve as the next base of operations for launching onward to new systems. For Tipler’s self-replicating machines, the primary limits to their expansion would be the availability of sufficient energy and raw materials for making each subsequent generation.

These radically different approaches highlight the challenges of making meaningful statements about interstellar migration. There are always a lot of big assumptions in any study like these. Some are reasonable and easily justifiable, but others are trickier. For example, all scenarios involve guesses about the scope of the technology used for interstellar travel. Furthermore, when the species is “along for the ride” rather than sending out sophisticated robotic emissaries, the most fundamental assumption is that living things can survive any kind of interstellar travel at all.

We know that traveling at even a paltry 10 percent of the speed of light requires some pretty wild technology—for example, fusion-bomb propulsion or colossal laser-driven light sails. There also has to be shielding from the hull-eroding impacts of interstellar gas atoms, as well as from starship-destroying crumbs of rock, each of which carries the punch of a bomb for a spacecraft at any decent fraction of light speed. Traveling at more modest speeds is potentially much safer but results in transit times between stars of centuries or millennia—and it is far from obvious how to keep a crew alive and well for time spans that may greatly exceed individual lifetimes.

The most contentious assumptions, though, revolve around questions of motivation and the projections we make about the longevity of entire civilizations and their settlements. For example, if an alien species is simply not interested in reaching other stars, the whole idea of galactic settlement literally stalls. This was one argument put forward by Carl Sagan and William Newman in 1983 as a rebuttal to what they called the “solipsist approach” to extraterrestrial intelligence. But as my colleague astronomer Jason Wright of the Pennsylvania State University points out, this kind of proposition is itself arguably a “monocultural fallacy.” To put this another way: it seems impossible to speculate with any accuracy about the behavior of an entire species as if it were thinking with one unified mind. We humans certainly do not fit in that box. And even if the vast majority of the Milky Way’s putative spacefaring civilizations do not attempt galactic diasporas, all it may take is one culture going against the grain to spread signs of life and technology across hundreds of billions of star systems.

In fact, the history of Fermi’s paradox is awash with diverse debates on its underlying suppositions, as well as with a huge variety of posited “solutions.” Few, if any, of these solutions are readily testable. Although some include ideas that are pretty straightforward, others are strictly science fiction. For example, it could be that the cost in resources of attaining the ability to rapidly traverse interstellar space is too high even for a superbly technological species. That could certainly trim the number of explorers and explain Hart’s fact A. Or perhaps population growth is not, as many researchers have supposed, a strong motivation for voyaging to the stars, especially for a species that restrains any rapacious impulses and develops a truly sustainable existence in its home system. The ultimate green revolution would remove the impetus to go farther afield for anything other than scientific exploration.

Sounding a more ominous note are concepts such as the “great filter”—the idea that there is something that always limits a species, perhaps an inevitable failure to achieve that green revolution, leading to an implosive extinction of all potentially technological life. Alternatively, maybe natural cataclysms, from supernovae explosions to outbursts from the Milky Way’s central black hole, simply prune galactic life regularly enough to keep it from becoming widespread.

More outrageous proposals include the zoo hypothesis. In this scenario, we are being kept deliberately isolated and in the dark by alien powers that be. There is also what I like to call the paranoia scenario: other civilizations are out there but are hiding from one another and refusing to communicate because of some kind of cosmic xenophobia.

Perhaps, though, there are simpler ways to explain our current ignorance about aliens. Those answers could share characteristics with the example right under our noses—the time-varying and patchy nature of human occupation in the islands of the South Pacific. In both terrestrial and extraterrestrial cases, there are basic, universal factors at play, from the scarcity of good places to drop anchor to the time it might take for a population to ready itself to push farther across the void.

Back in 2015 my colleague Adam Frank of the University of Rochester and I were having lunch near Columbia University’s campus in New York City. As at Fermi’s lunch 65 years earlier, the conversation was about the nature of spacefaring species. And inspired by Fermi’s spur-of-the-moment mental calculation, we were trying to craft an investigative strategy that made the fewest possible unsubstantiated assumptions and that could be somehow tested or constrained with real data. At the center of this exercise was the simple thought that, just as with Pitcairn Island’s transitory occupants, waves of exploration or settlement could come and go across the galaxy, with humans happening to emerge in one of the lonely periods.

This idea relates to Hart’s original fact A: that there is no evidence here on Earth today of extraterrestrial explorers. But it goes further by asking whether we can obtain meaningful limits on galactic life by constraining the exact length of time over which Earth might have gone unvisited. Perhaps long, long ago aliens came and went. A number of scientists have, over the years, discussed the possibility of looking for artifacts that might have been left behind after such visitations of our solar system. The necessary scope of a complete search is hard to predict, but the situation on Earth alone turns out to be a bit more manageable. In 2018 another of my colleagues, Gavin Schmidt of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, together with Frank, produced a critical assessment of whether we could even tell if there had been an earlier industrial civilization on our planet.

As fantastic as it may seem, Schmidt and Frank argue—as do most planetary scientists—that it is actually very easy for time to erase essentially all signs of technological life on Earth. The only real evidence after a million or more years would boil down to isotopic or chemical stratigraphic anomalies—odd features such as synthetic molecules, plastics or radioactive fallout. Fossil remains and other paleontological markers are so rare and so contingent on special conditions of formation that they might not tell us anything in this case.

Indeed, modern human urbanization covers only on the order of about 1 percent of the planetary surface, providing a very small target area for any paleontologists in the distant future. Schmidt and Frank also conclude that nobody has yet performed the necessary experiments to look exhaustively for such nonnatural signatures on Earth. The bottom line is, if an industrial civilization on the scale of our own had existed a few million years ago, we might not know about it. That absolutely does not mean one existed; it indicates only that the possibility cannot be rigorously eliminated.

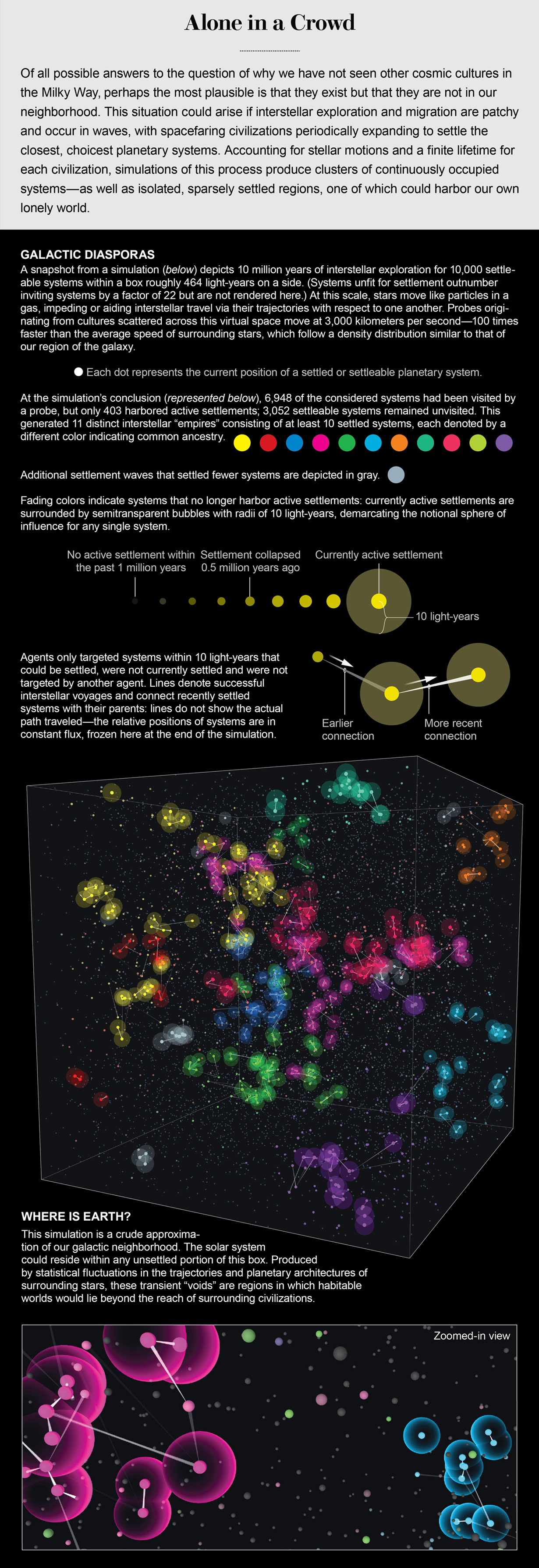

Over the past several years we have pursued the grander, galaxy-wide implications of these ideas in an investigation led by Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback of the University of Rochester and with Wright. A key advance has been the development of a series of agent-based computer simulations, backed up by old-fashioned paper-and-pencil mathematics, which has enabled us to build a more realistic picture of how species might move around in a galaxy that is itself full of motion.

If you take a snapshot of stars within a couple of hundred light-years of the sun, you will find that they are moving like the particles in a gas. Relative to any fixed point in this space, a star may be moving rapidly or slowly and in what is effectively a random direction. Zoom out farther, to scales of thousands of light-years, and you will begin to register the grand, shared orbital motion that carries a star such as our sun around the Milky Way once every 230 million years or so. Stars much closer to the galactic center take much less time to complete a circuit, and there are fast-moving “halo” stars diving in and out of the plane of the galactic disk as part of a distinct, rather spherically shaped swarm surrounding that disk.

What this means is that for a civilization looking around itself for target stars to explore, what is closest and what will be closest in the future vary significantly over time. A good illustration of this is our own solar system. Right now our nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is 4.24 light-years away, but in about 10,000 years it will be only 3.5 light-years distant—a significant savings in interstellar travel time. If we were to wait until about 37,000 years from today, our nearest neighbor would for a time be a small red dwarf star called Ross 248, which would then be a mere three light-years from us.

To model this shifting stellar map, our simulation uses a three-dimensional box of stars, with movements akin to those in a small part of a real galaxy. It then initiates a “front” of settlement by assigning a selection of those stars as hosts to spacefaring civilizations. Those civilizations have finite life spans, so a system can also become unoccupied. And a civilization has a waiting period before it is capable of launching a probe or settlement effort to its nearest neighboring star. All these factors can be altered, tweaked and explored to see how they affect the outcome. For a wide range of possibilities, a somewhat raggedy-looking settlement front self-propagates through interstellar space. The speed of this propagating front is the key to cross-checking and confirming possible solutions to Fermi’s original puzzle.

What we find is both simple and subtle. First, the natural, gaslike motion of stars in the galaxy means that even the slowest interstellar probes, moving at some 30 kilometers per second (nearly twice as fast as Voyager 1’s current speed of 17 kilometers per second in its outbound motion from our sun), would ensure that a settlement front would cross the galaxy in much less than a billion years. If we factor in other stellar motions, from galactic rotation or halo stars, this time span only shrinks. In other words, just as Fermi saw, it is not hard to fill the galaxy with life. But it is also the case that exactly how “filled” the galaxy becomes depends on both the number of genuinely settleable worlds out there—what we have dubbed the Aurora effect in homage to Kim Stanley Robinson’s epic 2015 science-fiction novel Aurora—and the length of the period civilizations are able to endure on a world.

At one extreme, it is easy to make the galaxy empty by simply shrinking the number of usable planets and having civilizations last for only, say, 100,000 years or so. At the other extreme, it is easy to tweak these factors to fill space with active spacefaring settlements. In fact, if suitable worlds are numerous enough, it almost does not matter how long settled civilizations last on average. If they retain the technology that allowed them to travel in the first place, then enough of them could carry on exploring and eventually fill the galaxy.

But it is between these extremes that the most compelling and potentially realistic situations arise. When the frequency of occurrence of settleable worlds in a galaxy is intermediate between high and very low, fascinating things can happen. Specifically, ordinary statistical fluctuations in the number and location of suitable worlds in patches of galactic space can create clusters of systems that are continually visited or resettled by wave after wave of interstellar explorers. Think of it as an archipelago, a group or chain of islands. The flip side to the existence of these clusters is that they are typically surrounded by large unsettled regions of space, places just too far and too sparsely distributed to bother setting out for.

Can this “galactic archipelago” scenario explain our situation on Earth? Remarkably, it may. For example, if typical planetary civilizations can last for a million years and if only 3 percent of star systems are actually settleable, there is a roughly 10 percent probability that a planet like Earth has not been visited in at least the past million years. In other words, it is not terribly unlikely that we would find ourselves on the lonely side of the equation.

Conversely, this scenario implies that elsewhere in the galaxy there are clusters, archipelagos, of interstellar species for whom cosmic neighbors or visitors are the norm. No extreme hypotheses are needed for any of this to take place; it would require just a rather ordinary accounting of planetary numbers and the nature of stellar movements amid the swirling stars of the Milky Way. And although it is true that assumptions linger about the feasibility of any kind of interstellar travel and about the likelihood that a species will actually undertake it, other factors are just parameters to be tuned. Some, such as the number of inhabitable worlds, are in astronomers’ sights already as we seek greater knowledge of exoplanets. Others, such as the longevity of civilizations, are the subject of intense scrutiny as we attempt to deal with our own issues of planetary sustainability.

The possibility also exists for us to discover evidence of settled stellar archipelagos or the ongoing propagation of a settlement front. Targeting our searches for extraterrestrial intelligence and technology not on individual, known exoplanets but rather on galactic regions where the topography of stars might lend itself to interstellar expansion or clustering could be an interesting new strategy. Until recently, our three-dimensional map of galactic space was woefully limited, but with instruments such as the European Space Agency’s Gaia observatory mapping a billion astronomical objects and stellar motions, we might be able to chart these hotspots.

In the end, though, the true paradox of Fermi’s paradox may be that there is no paradox at all. What my colleagues’ work shows is that it is an entirely natural state for a habitable, inhabited world such as Earth to exhibit no discernible evidence of having ever been visited or settled by an extraterrestrial species. This is true whether the galaxy is devoid of other technologically advanced life or is as teeming as it can be with interstellar explorers. Just as Pitcairn may have sat unoccupied for as much as three centuries in the Pacific Ocean, Earth might simply be passing through a period of isolation before the cosmic ripple of pan-galactic life washes over it once again.

The real question, as it was for Polynesian settlers across the centuries, is whether our planetary civilization will still be here when that happens.