Fiction

Power on Trial

In a future where people hold the perpetrators of the climate crisis to account, what has changed?

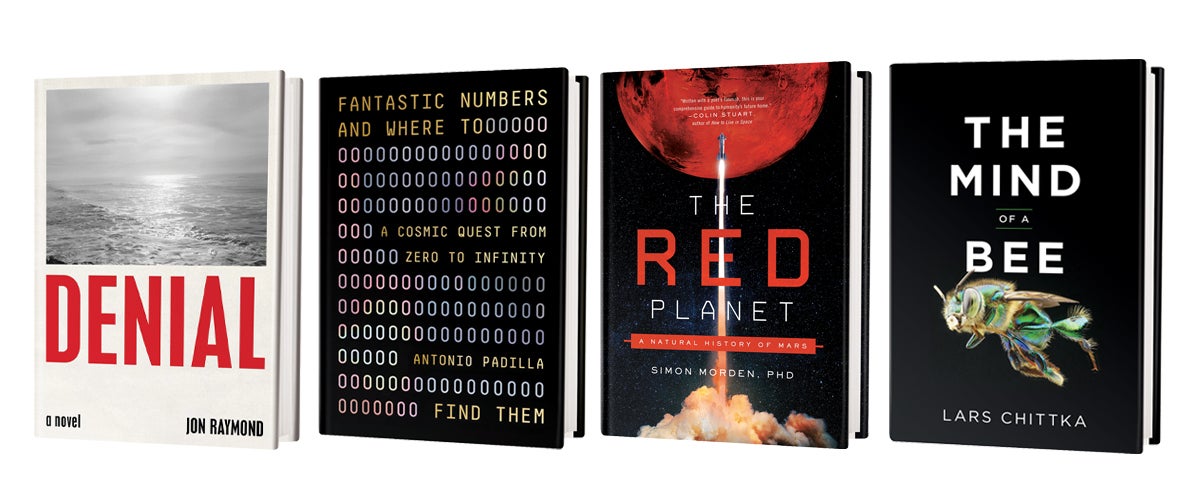

Denial: A Novel

by Jon Raymond

Simon & Schuster, 2022 ($26)

Writing science fiction is often a form of activism. The act of writing fiction generally can be said to spring from a place of hope—a celebration of what’s best in us, an attempt to imagine a less terrible reality. But most genres lack the audacity to scrap the rules of physics and technology to create worlds where the seemingly intractable problems of today can be solved or transformed so dramatically that we set aside our preconceived notions to embrace a fresh perspective.

This is why storytelling plays such a crucial role in the fight to find a way out of the climate crisis. If we’re going to make the huge sacrifices that are needed—if we’re going to change as a species, in other words—we’ll have to replace our old, outdated narratives. That’s the power of great activism.

Jon Raymond’s Denial is premised on this kind of radically hopeful outlook. It’s set in a future that’s been devastated by climate change—but not as badly as it could have been, thanks to the kind of unified, difficult, transformative change that our current world seems so incapable of making. Protest movements have successfully broken the power of the companies that profited from environmental devastation, and the executives who masterminded such exploitation were put on trial and locked up for life.

I want so badly to believe in this future, that we can change our behavior and hold the worst profiteers accountable. But Denial does not go far enough to convince me that it’s possible. Oddly, the world itself seems too familiar and even banal, even though we’re repeatedly assured that big shifts have taken place. There are occasional references to distant wildfires and hologram communications, but coffee shops, basketball games and road trips all remain unchanged. At one point the protagonist’s car breaks down in a small Mexican village, and he’s unable to meaningfully communicate with Spanish speakers. Yet the technology for effortless (if imperfect) translation already exists on every smartphone, and the fact that Raymond missed this opportunity to imagine a future with realistic details is one of many glaring distractions.

I can appreciate the desire to present a world that’s similar enough to our own—to connect the dots between the bleak present and a scenario where only the worst outcomes were avoided. But certainly any forces that are strong enough to crumble structures of power would shift culture and progress as well.

It has been said that genre is a conversation, and anyone is welcome to join in at any point. Denial is Raymond’s fourth novel and seems to be his first work of science fiction. Some of my favorite works of speculative fiction, for instance, are by genre outsiders, such as Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad. But if you’re dropping into a dialogue that has a rich history, contributions that might seem compelling and new to you may already have been discussed at length. The impression one gets is of a writer excited about the possibilities and history of the genre but not clued in to its diverse present.

In the end, the book’s biggest challenge is not a matter of genre but of character. The protagonist is a journalist who tracks down one of the most notorious corporate executives who escaped punishment—a kind of climate change version of Eichmann in Argentina—and befriends him to nail him with a spectacular on-camera confrontation and arrest. I love this fresh concept, exploring how we could hold people accountable for crimes against the planet.

The problem is, our journalist narrator doesn’t give much attention to the underlying issues at stake. He grapples in the abstract with the ethics of sentencing a kind old man to die in prison while acknowledging that the man deserves to be punished. But he himself has no strong feelings on the larger themes of climate destruction or the ambivalence many of us feel toward radical, necessary change. If he’d hated the former executive’s guts or believed that punishing individuals for collective behavior is profoundly wrong, I would have cared more about the character and his arc. But his motivation feels flimsy. Given the promising plot, the experience of watching it unfold is curiously empty.

Climate fiction (often shortened to “cli-fi”) is its own genre now, with many emotionally resonant novels and short stories that successfully imagine better futures and galvanize readers to action. Recent books such as Claire North’s Notes from the Burning Age and Becky Chambers’s A Psalm for the Wild-Built have imagined bright, beautiful—and hard, troubling—futures while rooting us in a vibrant central character who wants and feels things so strongly that the reader does, too. In these worlds, humanity has changed at a great cost and after great suffering while retaining a strong familiarity. This is the exciting tension that the best stories about the climate crisis navigate well: Which parts of “human nature” are immutable, and which are socially determined and subject to change?

We need more brave books like Denial that imagine a future that’s not dystopic—but that can show us how we might get there and who we’ll become when we do. —Sam J. Miller

Nonfiction

Lively Numbers

Finding awe in unsolved equations

Fantastic Numbers and Where to Find Them: A Cosmic Quest from Zero to Infinity

by Antonio Padilla

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022 ($30)

Cosmologist Antonio Padilla’s Fantastic Numbers and Where to Find Them is an exceptional compilation of modern mathematics and its real-world applications. Nothing is clearer than Padilla’s love for his work, which will be particularly inviting to lay readers. In a subject that can cause some eyes to glaze over, this is a fast-paced and dramatic telling of the history of mathematics that is ultimately concerned with convincing us why we should care. As Padilla guides readers from the imperceptibly small numbers (what does 10−120 really look like?) to the existentially large ones (the rate of expansion of our known universe) that surround, bump up against and bounce off us all, he performs the herculean task of not getting lost in the minutiae.

Conceptualizing the real-world application of abstract mathematics is every professor’s dream for their students, and Padilla makes it a reality. In conversational style, he jokes with the reader, frequently making colloquial asides and drawing pictures—using twin sea snakes, for instance, to portray frequency in electromagnetic radiation. Padilla bends light through Jell-O, explains entropy by invoking the soccer rivalry between Manchester and Liverpool, and walks us through Max Planck’s work by referencing Squid Game, the massively popular Korean TV series.

Readers are urged to consider heady concepts such as the relativity of time through popular knowledge (such as Usain Bolt’s sprinting speed)—but never without guidance. Padilla takes great effort to hold our hands through the discoveries he wants us to make; just as we’re feeling existentially overwhelmed in imagining the squeeze of spacetime, he leads us to the uncertainty principle, for example, with a punny line to assure us that we’ve safely made it to the finish line. There is no quantum entanglement to be found here.

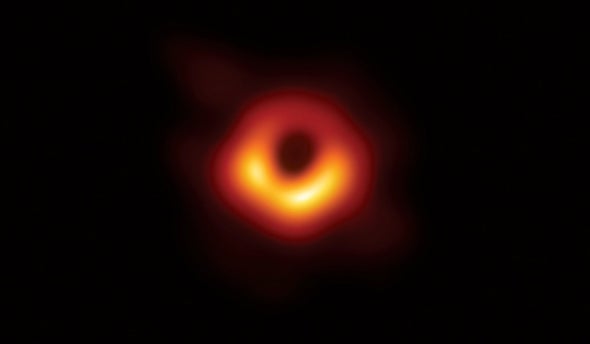

Physics and the mathematical equations we use to understand our universe can seem almost impossible, too big or too small or too weird to be real. But Padilla shows us there is nothing more exciting than a math equation left unsolved: Is gravity real? What does the surface of a black hole look like, and is it actually black? Is googol a number any actual layperson has ever needed to use? Why are the answers to these questions not so simple?

Perusing this book will leave readers with awe, enough fun facts for many cocktail parties, and a deep appreciation for mathematicians like Padilla who can explain how understanding a googolplex leads us to the existence of doppelgängers. —Brianne Kane

In Brief

The Red Planet: A Natural History of Mars

by Simon Morden

Pegasus Books, 2022 ($26.95)

Contemplating outer space can just as easily spark existential dread as it can incite wonder. But The Red Planet, a geological and historical survey of our solar system neighbor, reads more like a compelling travel guide. Simon Morden, an award-winning science-fiction writer with a doctorate in geophysics, embraces both these backgrounds with gusto whether he’s explaining the emergence of volcanoes on the planet or fantasizing about swimming in Martian saltwater. When the planet was in its infancy, Morden situates readers on the “ropey” and “blocky” surface; later in Mars’s life, dust storms create “a low susurrus of sound, a thousand whispers just on the other side of our spacesuit helmets.” The Red Planet does not break new ground in terms of scientific findings (don’t expect big scoops about life on Mars, for instance). But this is space writing at its finest, laying out extraterrestrial mysteries and convincing us to care. —Maddie Bender

The Mind of a Bee

by Lars Chittka

Princeton University Press, 2022 ($29.95)

Complex alien minds are all around us and deserve more of our curiosity and respect. This is the argument at the heart of The Mind of a Bee, a thorough and thoughtful primer on the interiority of bees. Once thought of as a simple, hive-minded species where individuals operate like cogs in a machine, bees are revealed here to be deeply intelligent and capable of rich sensory experiences. Recent work, for example, indicates that they can picture shapes and objects in their minds. Author Lars Chittka pulls from his background as a behavioral ecologist, deftly weaving between history and primary and secondary research to map the ways bees learn about the world around them, develop unique personalities, and perhaps even understand self and emotion. His reflections prompt questions about how bees are treated by humans, making this intimate portrait of one of Earth’s most important species appealing to enthusiasts and researchers alike. —Mike Welch