No one in her village faced food shortages during the lockdowns, nor did they suffer from COVID-19, Moligeri Chandramma assured me through an interpreter in March 2021. A farmer in the drylands of southern India, she grows more than 40 species and varieties of crops—mostly native millets, rice, lentils and spices—on a bit more than a hectare of land. Chandramma is a member of the Deccan Development Society (DDS), a cooperative of nearly 5,000 Dalit (oppressed caste) and Adivasi (Indigenous) women whose remarkable integration of biodiversity conservation with agricultural livelihoods earned them the United Nations’ prestigious Equator Award in 2019. Emerging from a situation of extreme malnutrition and social and gender discrimination in the 1980s, these farmers now enjoy food sovereignty and economic security. Not only are they weathering the pandemic, but in 2020 each family in DDS contributed around 10 kilograms of food grains to the region’s relief effort for those without land and livelihoods.

On the other side of the world, six Indigenous Quechua communities of the Peruvian Andes govern the Parque de la Papa (Potato Park) in Pisac, Cusco, a mountainous landscape that is one of the original homelands of the potato. They protect the region as a “biocultural heritage” territory, a trove of biological and cultural riches inherited from ancestors, and conserve more than 1,300 varieties of potato. When I visited in 2008 with other researchers and activists, I was stunned into silence by the diversity.

“This is the outcome of 20 years’ consistent work in relocalizing our food system, from a time when we had become too dependent on outside agencies for our basic needs,” farmer Mariano Sutta Apocusi told

In Europe, many “solidarity economy” initiatives, which promote a culture of caring and sharing, swung into action when COVID-related lockdowns rendered massive numbers of people jobless. In Lisbon, Portugal, the social centers Disgraça and RDA69, which strive to re-create community life in an otherwise highly fragmented urban situation, reached out with free or cheap food to whoever needed it. They provided not only meals but also spaces where refugees, the homeless, unemployed young people and others who might otherwise have fallen through the cracks could interact with and develop relationships with better-off families, creating a social-security network of sorts. The organizers trusted those with adequate means to donate food or funds to the effort, strengthening the feeling of community in surrounding neighborhoods.

The pandemic has exposed the brittleness of a globalized economy that is advertised as benefiting everyone but in fact creates deep inequalities and insecurities. In India alone, 75 million people fell below the poverty line in 2020; globally, hundreds of millions who depend for their survival and livelihoods on the long-distance trade and exchange of goods and services were badly hit. Similar, albeit less extreme, dislocations also appeared during the 2008 financial crisis, when commodity speculation, along with the diversion of food grains to biofuel production,

The value of these alternative ways of living goes far beyond their resilience during relatively short-term upheavals like the pandemic, however. As a researcher and environmental activist based in a “developing” country, I have long advocated that the worldviews of peoples who live close to nature be incorporated into global strategies for wildlife protection, such

In 2014 a few of us in India initiated a process to explore pathways to a world in which people are at peace with one another and with nature. Five years later (and fortuitously, just before the pandemic hit), the endeavor grew into an international

Such values are at odds with globalization, which delivers to denizens of the Global North (the better off, no matter where we live) many things that we have come to regard as essential. In contrast to the promise of ever increasing material wealth that underpins our civilization, people who live near or beyond its margins have a multitude of visions for living well, each tailored to the specifics of their ecosystems and cultures. To walk away from the cliff edge of irreversible destabilization of the biosphere, I believe we must enable alternative structures, such as those of the Dalit farmers, the Quechua conservers and the Lisbon volunteers, to flourish and link up into a tapestry that ultimately covers the globe.

An Enlightening Journey

Growing up in India, where lifestyles that are

Our activism would teach us at least as much as we learned in school and college. While investigating the sources of Delhi’s air pollution, for instance, we interviewed villagers who lived around a coal-fired power plant just outside the city. They turned out to be far worse affected by its dust and pollution than we city dwellers were—although they got none of its electricity. The benefits of the project flowed mainly to those who were already better off, whereas the disempowered experienced most of the harms.

In late 1980 we traveled to the western Himalayas to meet the protagonists of the iconic

Soon after, my friends and I learned that 30 major dams were to be constructed on the Narmada River basin in central India. Millions worshipped the Narmada as a tempestuous but bountiful goddess—so pristine that the Ganga is believed to visit her every year to wash away her sins. Trekking, boating and riding buses along its length of 1,300 kilometers, we were dazzled by waterfalls plunging into spectacular gorges, densely forested slopes teeming with wildlife, fields of diverse crops, thriving villages and ancient temples, all of which would be drowned. We

Over the years I came to understand how powerful economic forces reach around the globe to intimately link social injustice with ecological destruction. The era of colonization and slavery vastly expanded the economic and military reach of some nation-states and their allied corporations, enabling the worldwide extraction of natural resources and exploitation of labor to feed the emerging industrial revolution in Europe and North America. Economic historians,

During my wanderings over the decades and especially while researching a

These interactions and eclectic reading gave me insights into a vital question I was investigating: What are the essential characteristics of desirable and viable alternatives? Happily, I was far from alone in this quest. At a degrowth conference in Leipzig in 2014, I was excited to hear Alberto Acosta, an economist and former politician from Ecuador, speaking on buen vivir, an Indigenous worldview founded on living well with one another and with the rest of nature. Although Acosta spoke no English and I spoke no Spanish, we tried excitedly to converse; subsequently,

Commonalities

Though dazzlingly diverse, the alternatives emerging worldwide share certain core principles. The most important is sustaining or reviving community governance of the commons—of land, ecosystems, seeds, water and knowledge. In 12th-century England, powerful people began fencing off, or “enclosing,” fields, meadows, forests and streams that had hitherto been used by all. Enclosures by landlords and industrialists expanded to Europe and accelerated with the industrial revolution, forcing tens of millions of dispossessed people to either become factory workers or emigrate to the New World, devastating native populations. Imperial nations seized large portions of continents and reconfigured the economies of the colonies, extracting raw materials for factories, capturing markets for exports of manufactured goods, and obtaining foods such as wheat, sugar and tea for the newly created working class. In this way, colonizers and their allies established a system of perpetual economic domination that generated the Global North and the Global South (the world of the marginalized, no matter where they live).

The wave of anticolonial movements in the first few decades of the 20th century, many of them successful, sparked fears that supplies of raw materials for industries and markets for finished goods of higher value would dry up. President Harry S. Truman responded by launching a program for alleviating poverty in what he described as “underdeveloped areas” with their “primitive and stagnant” economies. As

As Elinor Ostrom, winner of the 2009 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, demonstrated, however, the commons are far more

Many of the efforts resemble the DDS and the Parque de la Papa in using community governance of commonly held resources to enhance agroecology (smallholder farming that sustains soil, water and biodiversity) and food sovereignty (control over all means of food production, including land, soil, seeds and the knowledge of how to use them). The food-sovereignty movement La Via Campesina, which originated in Brazil in 1993, now includes about 200 million farmers in 81 countries. Such attempts at self-reliance and community governance extend also to other basic needs, such as for energy and water. In Costa Rica, Spain and Italy, rural cooperatives have been generating electricity locally and controlling its distribution since the 1990s. And hundreds of villages in western India have moved toward “water democracy,” based on decentralized harvesting of water and community management of wetlands and groundwater.

Secure rights to govern the commons are also important. In the Ecuadorian Amazon, the Sapara Indigenous people

Greening cities or making them more welcoming, as the Lisbon social centers do, also requires community-based governance and economies of caring and sharing. Across the Global South, development projects have driven hundreds of millions of people to cities, where they live in slums and work in hazardous conditions. Wealthy city dwellers could do their part by consuming less, which would reduce the extraction and waste dumping that displace people in faraway places. A spectrum of avenues toward more

Five Petals

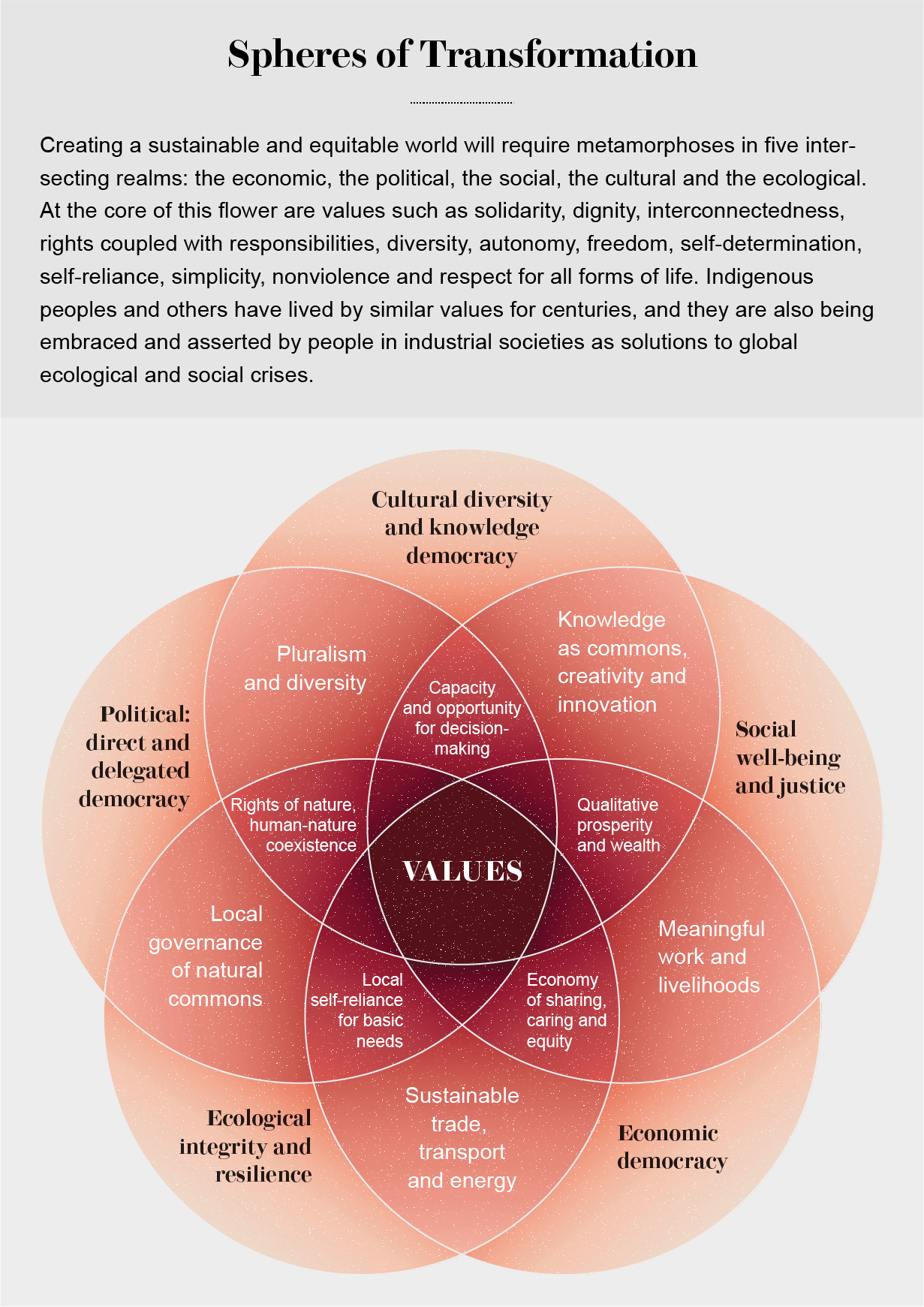

These initiatives point to the need for fundamental transformations in five interconnected realms. In the economic sphere, we need to get away from the development paradigm—including the notion that economic growth, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), is the best means of achieving human goals. In its place, we need systems for respecting ecological limits, emphasizing well-being in all its dimensions and localizing exchanges to enable self-reliance—as well as

We also need freedom from centralized monetary and financial control. Many experiments in

In many parts of the world, workers are seeking to control the means of production: land, nature, knowledge and tools. A few years back I visited Vio.Me, a detergent factory in Thessaloniki, Greece, which workers had taken over and converted from chemical to olive-oil-based and eco-friendly production, and where they had established complete parity in pay, regardless of what job the worker was doing. The slogan on their wall proclaimed: “We have no boss!”

In fact, work itself is being redefined. Globalized modernity has created a chasm between work and leisure—which is why we wait desperately for the weekend! Many movements seek to bridge this gap, enabling greater enjoyment, creativity and satisfaction. In industrial countries, people are bringing back manual ways of making clothes, footwear or processed foods under banners such as “The future is handmade!” In western India, many young people are leaving soul-killing routines in factories to

In the political sphere, the centralization of power inherent in the nation-state, whether democratic or authoritarian, disempowers many peoples. The Sapara nation in Ecuador and the Adivasis of central India argue for a more

Such a notion of democracy also challenges the boundaries of nation-states, many of which are products of colonial history and have ruptured ecologically and culturally contiguous areas. The Kurdish people, for instance, are split among Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. For three decades they have struggled to achieve autonomy and direct democracy based on principles of ecological sustainability and

Moving toward such radical democracy would suggest a world with far fewer borders, weaving tens of thousands of relatively autonomous and self-reliant communities into a tapestry of alternatives. These societies would connect with one another through “horizontal” networks of equitable and respectful exchange, as well as through “vertical” but downwardly accountable institutions that manage processes and activities across the landscape.

Several experiments in bioregionalism at large scales are underway, although most remain somewhat top-down in their governance. In Australia, the

Local self-governance may, of course, be oppressive or exclusionary. The intensely patriarchal and casteist traditional village councils in many parts of India and the xenophobic antirefugee approaches of the right wing in Europe illustrate this drawback. A third crucial sphere of transformation is therefore social justice, encompassing struggles against racism, casteism, patriarchy, and other traditional or modern forms of discrimination and exploitation. Fortunately, success in defying the dominant economic system often goes hand in hand with victories against discrimination, such as Dalit women farmers’ shaking off centuries of caste and patriarchal oppression to achieve food sovereignty.

Political autonomy and economic self-reliance need not mean isolationism and xenophobia. Rather cultural and material exchanges that maintain local self-reliance and respect ecological sustainability would replace present-day globalization—which perversely allows goods and finances to flow freely but stops desperate humans at borders.

Radical change also necessitates transformations in a fourth sphere: that of culture and knowledge. Globalization devalues languages, cultures and knowledge systems that do not adapt to development. Several movements are confronting this homogenizing tendency. The Sapara nation is trying to resuscitate its almost extinct language and preserve its knowledge of the forest by bringing these into the curriculum of the local school, for instance. Many communities are

One problem is that present-day educational institutions train graduates who are equipped to serve and perpetuate the dominant economic system. People are bringing community and nature back into spaces of learning, however. These efforts include Forest Schools in many parts of Europe that provide children with hands-on learning in the midst of nature, the Zapatista autonomous schools that teach about diverse cultures and struggles, and the Ecoversities Alliance of centers of higher learning around the world that enable scholars to seek knowledge across the boundaries that typically separate academic disciplines.

The most important sphere of transformation, however, is the ecological—recognizing that we are part of nature and that other species are worthy of respect in their own right. Across the Global South, communities are leading efforts to regenerate degraded ecosystems and wildlife populations and conserve biodiversity. Tens of thousands of “territories of life” are being governed by Indigenous or other local communities, for example. These include locally managed marine areas in the South Pacific, Indigenous territories in Latin America and Australia, community forests in South Asia, and the Ancestral Domain territories in the Philippines. Also noteworthy is legislation or court judgments in several countries asserting that rivers, for example,

Values

I am often asked how one scales up successful alternatives. It would be self-defeating, however, to try to either scale up or replicate a DDS or a Parque de la Papa. The essence of this approach is diversity: the recognition that every situation is different. What people can do—and this, indeed, is how successful initiatives spread—is understand the underlying values and apply these in their own communities while networking with like ventures to spread the impact.

The Vikalp Sangam process has identified the following values as crucial: solidarity, dignity, interconnectedness, rights and responsibilities, diversity, autonomy and freedom, self-reliance and self-determination, simplicity, nonviolence, and respect for all life. Around the world both ancient and modern worldviews that are focused on life articulate similar principles. Indigenous peoples and other local communities have lived by worldviews such as buen vivir, swaraj, ubuntu (an African philosophy that sees the well-being of all living things as interconnected) and many other such ethical systems for centuries and are reasserting them. Simultaneously, approaches such as degrowth and ecofeminism have emerged from within industrial societies, seeding powerful countercultures.

At the heart of these worldviews lies a simple principle: that we are all holders of power. That in the exercise of this power, we not only assert our own autonomy and freedom but also are responsible for ensuring the autonomy of others. Such a swaraj merges with ecological sustainability to create an eco-swaraj, encompassing respect for all life.

Clearly, such fundamental transformations face a deeply entrenched status quo that retaliates violently wherever it perceives a threat. Hundreds of environmental defenders are murdered every year. Another serious challenge is the unfamiliarity many people in the Global North have with ideals of a good life beyond the American dream. Even so, the fact that many progressive initiatives are thriving and new ones are sprouting suggests that a combination of resistance and

The COVID pandemic is a catastrophe that presents humankind with a choice. Will we head right back toward some semblance of the old normal, or will we adopt new pathways out of global ecological and social crises? To maximize the likelihood of the latter, we need to go well beyond the Green New Deal approaches in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere. Their intense focus on the climate crisis and worker rights is valuable, but we also need to challenge unsustainable consumption patterns, glaring inequalities and the need for centralized nation-states.

Truly life-sustaining recoveries would emphasize all the spheres of eco-swaraj, arrived at via four pathways. One is the creation or revival of dignified, secure and self-reliant livelihoods for two billion people based on collective governance of natural resources and small-scale production processes such as farming, fisheries, crafts, manufacturing and services. Another is a program for regeneration and conservation of ecosystems, led by Indigenous peoples and local communities. A third is immediate public investments in health, education, transportation, housing, energy and other basic needs, planned and delivered by local democratic governance. Finally, incentives and disincentives to make production and consumption patterns sustainable are crucial. These approaches would integrate sustainability, equality and diversity, giving everyone, especially the most marginalized, a voice. A proposal for a million climate jobs in South Africa is of this nature, as is a feminist recovery plan for Hawaii and several other proposals for social justice in other countries.

None of this will be easy, but I believe it is essential if we are to make peace with Earth and among ourselves.