Sadness. Disappointment. Frustration. Anger. These are some of the reactions from LGBTQ+ astronomers over the latest revelations regarding NASA’s decision not to rename the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), given that the agency long had evidence suggesting its Apollo-era administrator James Webb was involved in the persecution of gay and lesbian federal employees during the 1950s and 1960s.

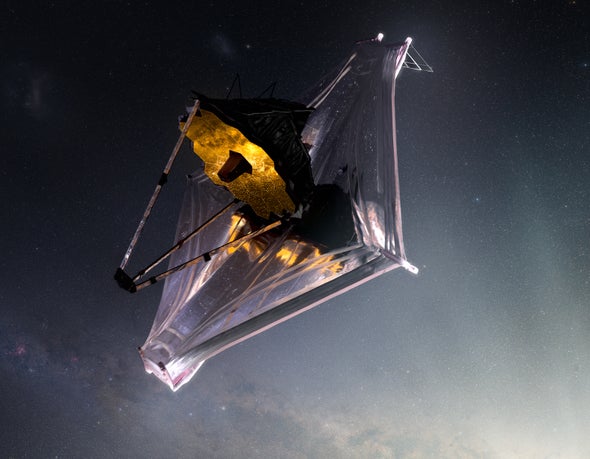

The new information came to light late last month when nearly 400 pages of e-mails were posted online by the journal Nature, which obtained the exchanges under a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Since early last year, four researchers have been leading the charge for NASA to alter the name of the $10-billion flagship mission, launched in December 2021, which will provide unparalleled views of the universe. The e-mails make clear that, behind the scenes, NASA was well aware of Webb’s problematic legacy even as the agency’s leadership declined to take his name off the project.

“Reading through the exchanges, it seems that LGBTQ+ scientists and the concern we raised are not really what they care about,” says Yao-Yuan Mao of Rutgers University, who maintains the online Astronomy and Astrophysics Outlist of openly LGBTQ+ researchers.

“It’s almost amusing how incompetent the whole thing was,” says Scott Gaudi, an astronomer at the Ohio State University, “and how little they stopped to think of how important an issue this was to the queer astronomical community and how important NASA is for young queer kids trying to find aspirational reasons to just keep going.”

As the successor to the renowned Hubble Space Telescope, JWST’s name is likely to one day be known by schoolchildren, suburban parents and senior citizens alike, which is why LGBTQ+ astronomers feel so strongly that the observatory’s namesake should not be someone who was allegedly involved in homophobic directives. Many of them see NASA’s resistance to renaming JWST as part of a dismaying trend in which the agency’s actions speak louder than—and counter to—its stated policy of fostering diversity and inclusion throughout its workforce. Last month, for example, NASA officials scrambled to explain their abrupt cancellation of an initiative to allow employees of its Goddard Space Flight Center to more easily display personal pronouns in intra-agency communications.

During a March 30 meeting of NASA’s Astrophysics Advisory Committee, officials said that the agency’s investigation into Webb’s potential involvement with LGBTQ+ persecution is still ongoing and that they expect to present a final report in the coming months. “I’m looking for additional evidence that may conflict with the understanding we currently have of Webb’s role in this,” said NASA’s acting chief historian Brian Odom. At the same meeting, the agency’s director of astrophysics Paul Hertz even offered some contrition, acknowledging that “the decision NASA made is painful to some, and it seems wrong to many of us.”

To repair its damaged reputation with the LGBTQ+ community, some astronomers say, the agency should now bow to mounting pressure and strike Webb’s name from its flagship telescope.

Renaming JWST would be “a simple but very impactful thing that NASA can do, both for astronomers and the wider public,” says Johanna Teske, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C. “Why would they not take the opportunity to do that and fulfill one of their core values?”

Originally known as the Next Generation Space Telescope, JWST was rechristened for Webb in 2002, a decision undertaken by Sean O’Keefe, NASA’s administrator at the time. Little was known then about Webb’s role in a period of mid-20th-century American history known as the Lavender Scare—a McCarthy-like witch hunt in which many gay and lesbian federal employees were seen as national security risks and subsequently surveilled, harassed and fired.

Prior to leading NASA, Webb was second-in-command at the U.S. Department of State. In a September 3, 2021, e-mail Nature obtained through FOIA, a redacted writer notes that archival documents paraphrased in a 2004 history book say, “Webb met with President [Harry S.] Truman on June 22, 1950 in order to establish how the White House, the State Department, and the Huey Committee might ‘work together on the homosexual investigation.’” A large number of LGBTQ+ workers were fired from the State Department before Webb resigned from his position there in 1952.

Critics say homophobia followed Webb to NASA. During his tenure as the agency’s administrator between 1961 and 1968—a critical time in its preparations to land astronauts on the moon—a suspected gay employee, Clifford Norton, was interrogated for hours about his sexual history by NASA’s security chief and ultimately fired for “immoral, indecent, and disgraceful conduct.” This was part of the basis for calls to rename JWST, which NASA responded to by conducting an internal investigation into Webb’s complicity in such actions.

On September 27, 2021, current agency administrator Bill Nelson released a one-sentence statement saying, “We have found no evidence at this time that warrants changing the name of the James Webb Space Telescope.” The announcement seems odd, given that, as early as April 2021, one redacted author in the newly released e-mails noted that the official who fired Norton testified the termination came about because his advisers had told him that dismissal for homosexual conduct was considered a “custom within the agency.”

Prior to Nelson’s statement, the redacted author of the September 3, 2021, e-mail strongly recommended changing the telescope’s name. “That Webb played a leadership position in the Lavender Scare is undeniable,” they wrote.

“It seems like, from the very beginning, the entire research effort was compromised by the fact that the goal was to dismiss the criticism they received,” says Lucianne Walkowicz, an astronomer at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago and one of the scientists leading the push to change JWST’s name.

Especially galling to many LGBTQ+ astronomers is an episode referenced in the e-mails in which Hertz stated he contacted more than 10 members of the astrophysics community—none of whom identified as LGBTQ+ and none of whom expressed disappointment at the prospect of JWST keeping its problematic name.

“I’ve worked closely with Paul Hertz for over a decade, and I consider him to be a colleague and a mentor,” Gaudi says. “He knows me. He knows I’m gay. And he didn’t ask me. Like, what the hell?”

The ad hoc nature of NASA’s response to this controversy highlights the fact that federal agencies rarely follow clear-cut methods for naming or renaming high-profile projects. Such decisions often appear to be taken at the whim of senior officials, with little regard for larger input from other stakeholders, including the public at large. In late 2019, for instance, the National Science Foundation renamed its currently under construction Large Synoptic Survey Telescope in honor of astronomer Vera C. Rubin, who was instrumental in the discovery of dark matter. According to Matt Mountain, president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, that change emerged from a suggestion made in the U.S. House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology rather than from any large grassroots effort.

NASA’s upcoming Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope was similarly renamed after Nancy Grace Roman, another pioneering astronomer and the first female executive at NASA, although in that case, the agency followed a formal policy directive for assigning names to major projects. Most of NASA’s name changes have occurred prior to a project’s completion or launch, but there is precedence for post-launch alterations, too. The Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Explorer was changed to the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, after its late principal investigator, while the National Polar-Orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System Preparatory Project was renamed after meteorologist Verner E. Suomi three months after it launched.

The cost of such undertakings—which involve changing official documents, Web sites and graphic designs—seems to be fairly negligible. The Rubin Observatory’s budget of roughly $40 million per year saw no significant increase during its name change, Mao says, suggesting that such switches carry minimal monetary risks for what could be substantial rewards.

“The change of name, in my opinion, uplifts the Vera Rubin science community,” Mao adds. “The name not only inspires me to do exciting science but also reminds me that there is a responsibility to make this field a more inclusive space.”

Some of the pushback to changing JWST’s name has come from those who insist he was not a hate-monger but merely a complicated figure—a man of his time who, like everyone, did some good and some bad.

“It is alluring to want to search for monsters,” Walkowicz says. “But I think monsters are a myth that we tell ourselves about how prejudice and discrimination is enacted. We’re too focused on a cartoonish idea of what discrimination looks like rather than how discrimination is a multilevel policy decision enacted by many people.” If Webb deserves credit for helping to place astronauts on the moon under his tenure, Walkowicz adds, then he also bears responsibility for homophobic actions conducted by his administration.

Regardless of how NASA proceeds going forward, the harm done to its relationship with the LGBTQ+ community will take time and effort to repair. “I’ve lost faith, and I think a lot of people have,” says Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, a theoretical cosmologist at the University of New Hampshire and another leader of the push for renaming JWST. But change remains possible, she says: “As scientists, we often realize we were in error, and we set a new course.”