For more than 20 years scientists have known that the drugs we take, for maladies ranging from headaches to diabetes, eventually make their way into our waterways—where they can harm the ecosystem and potentially promote antibiotic resistance.

But most research on pharmaceutical contaminants has been done in North America, Europe and China and has examined just a small subset of compounds. The studies also use a variety of sampling and analysis methods, making it hard to compare results. Such limitations mean scientists may be missing a big piece of the pollution puzzle.

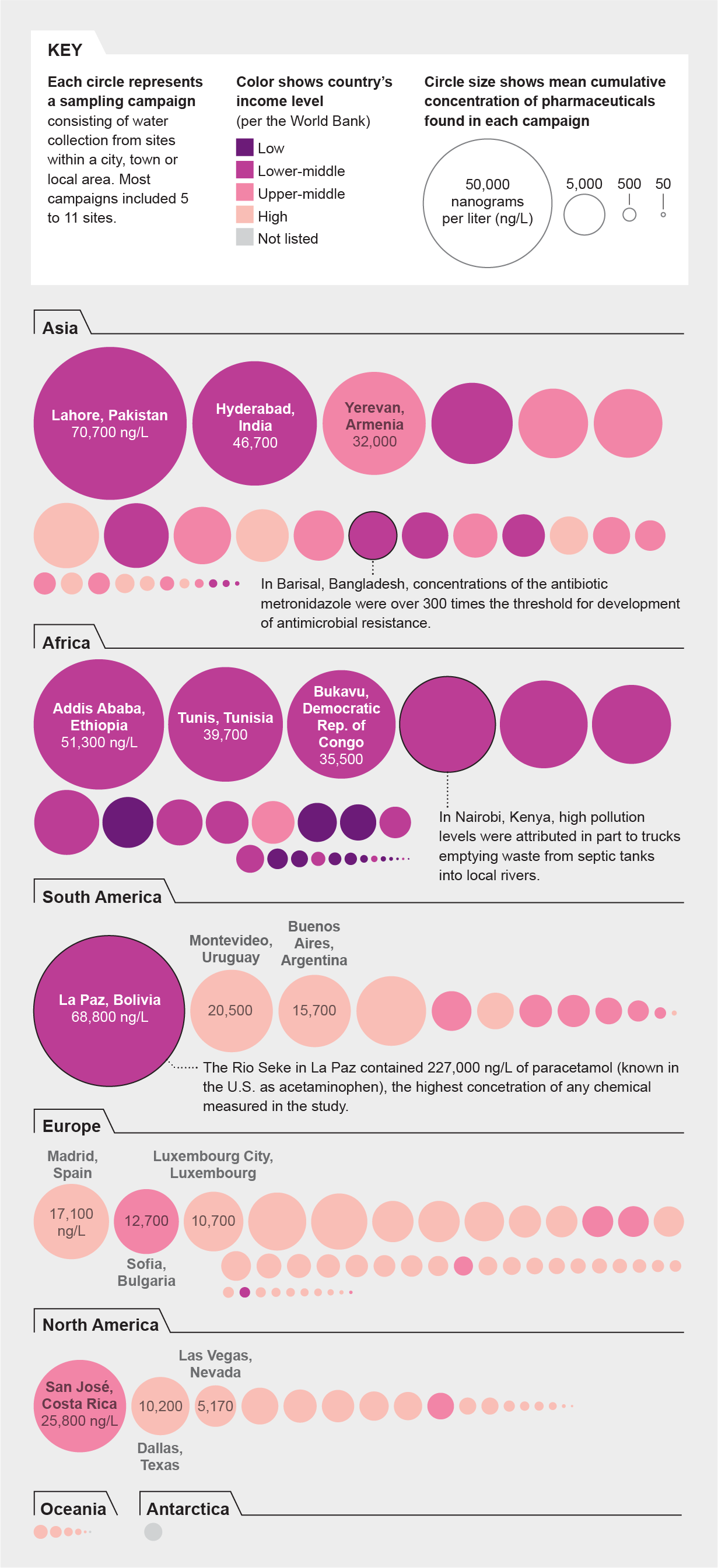

A new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA provides a more comprehensive look. A network of 127 scientists sampled 258 rivers in 104 countries for 61 different chemicals, producing “a sort of ‘pharmaceutical fingerprint’ of nearly half a billion people across all the world's continents,” says study lead author John L. Wilkinson, an environmental chemist at the University of York in England.

Many of the most drug-polluted rivers were in Africa and Asia, “in areas and countries that have been largely forgotten by the scientific community” on this issue, Wilkinson says. Waterways with the biggest pharmaceutical concentrations also tended to be in lower-middle-income countries; the authors say this could stem from improved medication access in places that still lack sufficient wastewater infrastructure.

Four compounds—caffeine, nicotine, acetaminophen and cotinine (a chemical produced by the body after exposure to nicotine)—showed up on every continent, including Antarctica. Another 14, including antihistamines, antidepressants and an antibiotic, were traced on all continents except Antarctica. Some drugs were detected only in specific places, such as an antimalarial found in African samples.

Overall, the study shows that “more of this kind of global assessment of aquatic pollution” is needed, particularly for other chemicals that pose more of a human health risk, says Elsie Sunderland, a Harvard University environmental scientist who was not involved with the new research. It also suggests, she adds, that “we need wastewater treatment.”