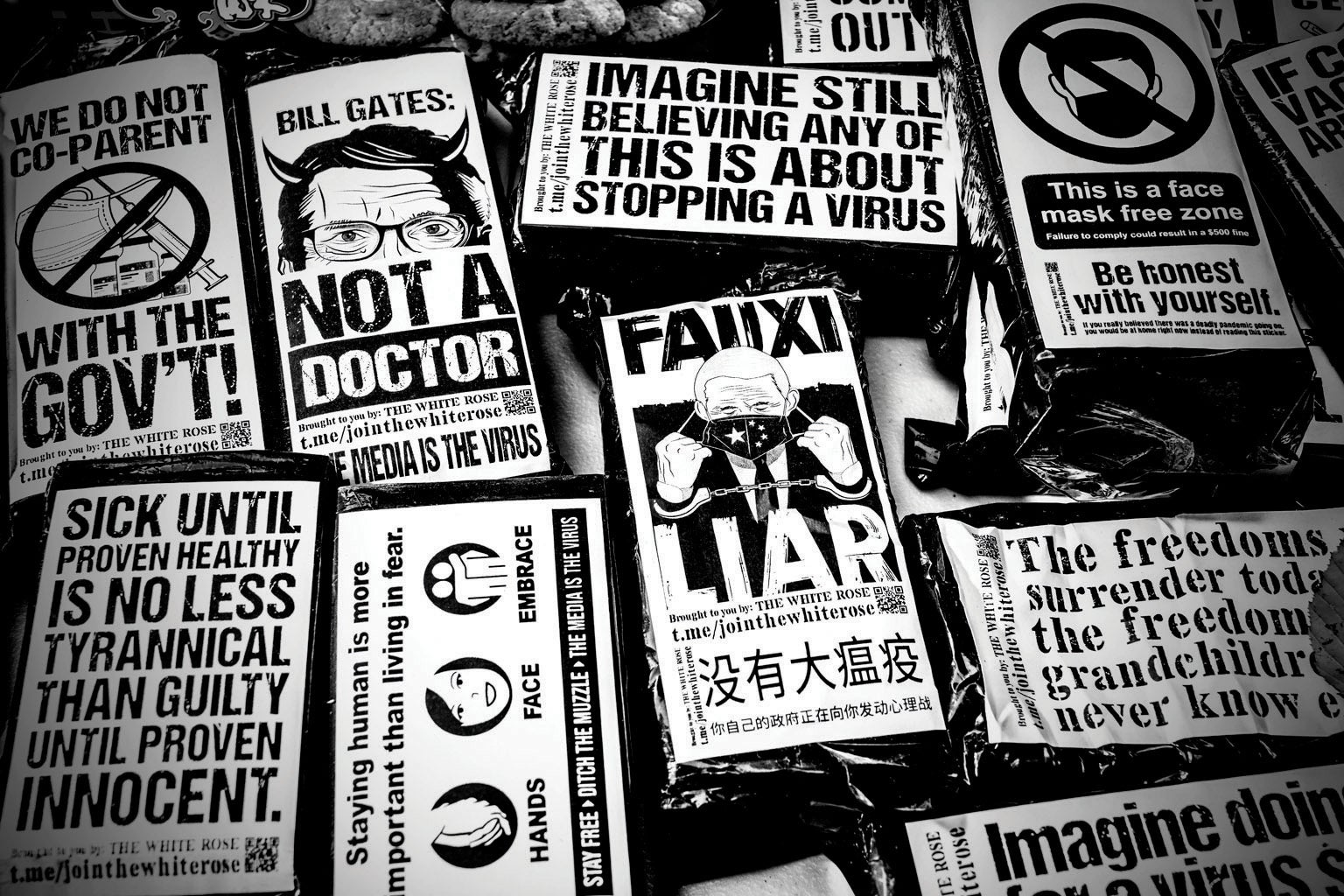

Whenever scientific findings threaten people’s sense of control over their lives, conspiracy theories are never far behind. The emergence of novel viruses is no exception. New pathogens have always been accompanied by conspiracy theories about their origin. These claims are often exploited and amplified—and sometimes even created—by political actors. In the 1980s the Soviet KGB mounted a massive disinformation campaign about AIDS, claiming that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had created HIV as part of a biological weapons research program. This campaign benefited from a “scientific” article written by two East German scientists that ostensibly ruled out a natural, African origin of the virus, an explanation favored by Western scientists that has since been unambiguously established. In African countries, where many scientists and politicians considered the hypothesis of an African origin of AIDS to be racist, the disinformation campaign fell on fertile ground. Ultimately the conspiracy theory was picked up by Western media and became firmly entrenched in the U.S. Similarly, when the Zika virus was spreading in 2016 and 2017, social media was awash in claims that it had been designed as a bioweapon.

From the beginning, the genomic evidence led most virologists who were investigating SARS-CoV-2 to favor a zoonotic origin involving a jump of the virus from bats to humans, possibly with the help of an intermediate host animal. But considering the anxiety-provoking upheavals of the pandemic, it came as no surprise that the virus inspired conspiratorial thinking. Some of these theories—such as the idea that 5G broadband rather than a virus causes COVID or that the pandemic is a hoax—are so absurd that they are easily dismissed. But some theories came with a patina of plausibility. Speculation that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was engineered in the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) in China was facilitated by the physical location of the institute: it is right across the Yangtze River from the Huanan market where many of the earliest cases of COVID were detected. The Chinese government’s denial that markets sold live wild animals also roused suspicion, even though such wares were always suspected and have since been confirmed.

The so-called lab-leak hypothesis gained sufficient rhetorical and political force that President Joe Biden instructed the U.S. intelligence services to investigate it. Although the interagency intelligence report update, declassified in October 2021, dismissed several popular laboratory-origin claims—including that the virus was a bioweapon and that the Chinese government knew about the virus before the pandemic—it was unable to unequivocally resolve the origin question.

Does this mean that proponents of the lab-leak hypothesis uncovered a genuine conspiracy that will be revealed by persistent examination? Or is the lab-leak rhetoric rooted in conspiracy theories fueled by anxiety over China’s increasing prominence on the world stage or in preexisting hostility to biotechnology and fear over biosecurity? And what is it about the conditions of the past two years that made it so difficult to know?

Zoonotic Origins

The ostensible lab-leak hypothesis is not a single identifiable theory but a loose constellation of diverse possibilities held together by the common theme that Chinese science institutions—be it the WIV or some other arm of the Chinese government—are to blame for the pandemic. At one end is the straightforward possibility of WIV lab personnel being infected during fieldwork or while culturing viruses in the lab. Scientifically, this possibility is challenging to disentangle from a zoonotic origin that followed other pathways and is therefore difficult to rule out or confirm. At the other extreme are the assertions that SARS-CoV-2 was designed and engineered by the WIV, perhaps as a bioweapon, and was released either accidentally or as a biological attack. This possibility necessarily entails a conspiracy among WIV scientists—and potentially many others—to first engineer a virus and then cover up its release. Scientific investigation of the genomic and phylogenetic evidence can help us determine whether SARS-CoV-2 was genetically engineered.

SARS-CoV-2 is a member of a subgenus of the betacoronaviruses called the sarbecoviruses, named after their prototype member, SARS-CoV-1, which caused the SARS epidemic in 2002 and 2003. The zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-1 has been firmly established by research that also showed that the bat sarbecoviruses pose a clear and present danger of pandemic overspill from bats to humans.

One key feature of sarbecoviruses is that they undergo extensive amounts of recombination. Parts of their genomes are being regularly swapped at a rate that implies a vast ecosystem of these viruses is circulating, most of which have not been discovered. The area of the genome that is most likely to recombine is also the area that encodes the “spike” proteins—the very proteins that play a crucial role in initiating an infection. Many sarbecoviruses encode spike proteins that can bind to a wide range of mammalian cells, suggesting that these viruses can easily move back and forth between different species of mammals, including humans.

SARS-CoV-2 is not as virulent as SARS-CoV-1, but it is transmitted far more easily between people. Two of the most prominent features of the SARS-CoV-2 spike are its receptor-binding domain (RBD), which binds very tightly to human ACE2, the protein that allows it to enter lung cells, and the so-called furin cleavage site (FCS). This site divides the spike protein into subunits. The FCS is present in many other coronaviruses, but so far SARS-CoV-2 is the only sarbecovirus known to include it. It allows the viral spike protein to be cut in half during its release from an infected cell, priming the virus to spread to new cells more efficiently.

The RBD and FCS are central to initial virological arguments by expert proponents of the lab-leak hypothesis. Such arguments are based on the supposition that neither the RBD nor the FCS “appears natural” and therefore that they can only be the product of lab-based engineering or selection. Nobel laureate David Baltimore, an early proponent of the lab-leak hypothesis, referred to the FCS as a “smoking gun” that points to a lab origin.

Although an unusual feature of a virus can legitimately stimulate further inquiry, this argument is reminiscent of the creationist claim that humans must have been “intelligently designed” because we are seemingly too complex to have evolved by natural selection alone. This logic is fundamentally flawed because complexity does not license dismissal of the overwhelming evidence for natural selection and, by itself, does not mandate any design, intelligent or otherwise. Likewise, labeling the RBD or the FCS “unnatural” does not mandate lab-based engineering, and, critically, it does not license the dismissal of the growing evidence for a zoonotic origin.

Recently, for example, bat colonies on the border between Laos and China were discovered to carry sarbecoviruses that have RBDs almost identical to those of SARS-CoV-2 in both sequence and ability to enter human cells. This finding refutes the claim that SARS-CoV-2’s binding affinity in humans is unlikely to have a natural origin.

Similarly, although some lab-leak proponents contend that the lack of an FCS in the closest relatives of SARS-CoV-2 is indicative of its manual insertion in a lab, very recent evidence from SARS-CoV-2 population sequencing suggests that the insertion of new sequences from human genes next to the FCS can be detected. Moreover, the closest relative of the SARS-CoV-2 spike in the Laotian bat viruses would require the addition of only a single amino acid to generate a putative FCS. Thus, in a species where it would have a major selective advantage, it would probably be very easy for some of these bat coronaviruses to rapidly evolve an FCS.

This research sketches a clear zoonotic path to the emergence of the RBD and FCS. Although some evolutionary gaps along this path persist, their number and size have been dwindling. A detailed analysis in late 2021 further strengthened the link to the Huanan markets as the point of origin of the virus and the initial source of community transmission. This rapidly growing body of evidence for a zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2 creates increasing difficulties for the lab-engineering hypothesis.

Conspiratorial Cognition

In normal scientific inquiry, as evidence emerges, the remaining space for plausible hypotheses narrows. Some facets continue to be supported, and others are contradicted and eventually precluded altogether. Some of the strongest advocates for a lab origin for SARS-CoV-2 changed their views as they learned more. Baltimore, for instance, withdrew his “smoking gun” comment when challenged by additional evidence, conceding that a natural origin was also possible. Revising or rejecting failed hypotheses in light of refuting evidence is central to the scientific process. Not so with conspiracy theories and pseudoscience. One of their hallmarks is that they are self-sealing: as more evidence against the conspiracy emerges, adherents keep the theory alive by dismissing contrary evidence as further proof of the conspiracy, creating an ever more elaborate and complicated theory.

There is perhaps no better example of self-sealing cognition than the contortions of climate change denial that erupted after the 2009 “Climategate” controversy. At that time thousands of documents and e-mails were stolen from the Climatic Research Unit of the University of East Anglia in England and made public right before the United Nations climate conference in Copenhagen. The e-mails were cherry-picked by deniers for sound bites that, when taken out of context, seemed to point to malfeasance by scientists. Ultimately nine independent inquiries around the world cleared the scientists of misconduct, and nine of the warmest years ever measured have occurred in the 11 years since Climategate.

Undeterred by the exonerations, climate deniers—including at least one U.S. congressperson—branded the inquiries as a “whitewash.” The volume of activity on skeptics’ Web sites relating to the hacked e-mails continued to increase for at least four years, long after the public had lost all interest in the confected scandal. It was only in late 2021 that one of the principals making unfounded accusations against the scientists apologized for his role.

The e-mails were publicly misrepresented as a result of an unsolved hack, but top scientists and health officials also have seen their correspondence become public through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests by groups with long histories of attacking scientists. The organization U.S. Right to Know honed its FOIA tactics against food scientists before turning its sights on virologists.* Despite e-mails clearly showing virologists considering but ultimately rejecting various claims about SARS-CoV-2 being engineered, lab-leak proponents tend to selectively quote messages. They cast virologists as either never having given lab scenarios fair consideration or—on the other extreme—believing in a lab origin all along and deliberately lying about it. People who push conspiracy theories often toggle between opposing claims as the rhetorical need arises.

Another e-mail-centered theory turned on the idea that the WIV had originally housed viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, presumably including the natural virus from which it had been engineered. The theory further held that the WIV suspiciously delayed publication of a paper that had been submitted in October 2019 until 2020. At some point after the paper’s submission with the “true” sequences, the argument went, the WIV halted its publication and altered the sequence information in furtherance of the cover-up.

Another FOIA effort was marshaled to reveal the discrepancy between the “real” sequences submitted to the journal and those that were pawned off on the unsuspecting public. Unfortunately for this conspiracy claim, the FOIA results revealed that the submitted paper’s sequences were exactly what the scientists publicly said they were. The self-sealing nature of conspiratorial reasoning being what it is, however, some proponents of the lab-leak hypothesis remain undeterred and believe the “real” sequences must exist in some as yet undocumented draft created before the submitted version.

The self-sealing dynamic can produce even more elaborate epicycles to resist falsification. Until earlier this year, the closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 was a virus called RaTG13, which is known to have been held by the WIV in a collection of bat swab samples. RaTG13 is more than 96 percent identical to SARS-CoV-2. It is likely that this virus genome was sequenced from a swab taken in 2013 from bats in an abandoned mine shaft in Mojiang, a county in China’s Yunnan province. RaTG13’s centrality to many lab-leak claims stemmed from its putative role as the “backbone” from which SARS-CoV-2 was allegedly engineered.

Being closely related to SARS-CoV-2 and being present in the lab at the WIV made RaTG13 a perfect candidate for a precursor that was engineered into SARS-CoV-2. In the short time since the pandemic took hold, however, several related viruses have been discovered that are closer in sequence to SARS-CoV-2 over much of the genome. Moreover, despite being related to SARS-CoV-2, RaTG13 has been found to occupy a separate phylogenetic branch. SARS-CoV-2 is not descended from RaTG13; rather the viruses share a common ancestor from which they diverged an estimated 40 to 70 years ago, meaning it could not have served as a backbone for an engineered SARS-CoV-2.

Rather than accepting this contrary evidence, some lab-leak advocates resorted to self-sealing reasoning that deviates from standard scientific practice: They began to argue that RaTG13 was not a natural virus itself but rather had been edited or in some way fabricated in an effort to hide the “true” backbone of SARS-CoV-2 and thus its engineered nature. The virus from Laos showing that SARS-CoV-2’s RBD and the efficiency of its binding to human receptors are not unique—providing strong support for a zoonotic origin—is thus reinterpreted to mean that the WIV obtained and used a similar but so far secret virus from Laos to design SARS-CoV-2. This ad hoc hypothesis is accompanied by the expectation that the burden is on the WIV to prove it did not have that secret virus—a reversal of the expected burden of proof that runs counter to conventional scientific reasoning.

Such pivots are potentially immune to further evidence. Just as there are effectively unlimited “gaps” between transitional fossils that are exploited by creationists, so, too, are there effectively unlimited potential natural viruses from which SARS-CoV-2 must have been engineered that have been kept hidden by the WIV. Or else unnatural viruses the WIV might have engineered to make SARS-CoV-2’s features seem naturally evolved.

More and more relatives and antecedents of SARS-CoV-2 are bound to be discovered, and adherents of the lab-leak hypothesis will face a stark choice. They can abandon, or at least qualify, their belief in genetic engineering, or they must generate an ever increasing number of claims that these relatives and antecedents, too, have been fabricated or engineered. It is likely that at least some people will follow the latter path of motivated reasoning, insisting that secretive Chinese machinations or an unnatural manipulation of biology is responsible for the virus’s origin.

Motivated reasoning based on blaming an “other” is a powerful force against scientific evidence. Some politicians—most notably former President Donald Trump and his entourage—still push the lab-leak hypothesis and blame China in broad daylight. When Trump baldly pointed the finger at China in the earliest days of the pandemic, unfortunate consequences followed. The proliferation of xenophobic rhetoric has been linked to a striking increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. It has also led to a vilification of the WIV and some of its Western collaborators, as well as partisan attempts to defund certain types of research (such as “gain of function” research) that are linked with the presumed engineering of SARS-CoV-2. There are legitimate arguments about the regulation, acceptability and safety of doing gain-of-function research with pathogens. But conflating these concerns with the fevered discussion of the origins of SARS-CoV-2 is unhelpful. These examples show how a relatively narrow conspiracy theory can expand to endanger entire groups of people and categories of scientific research—jeopardizing both lives and lifesaving science.

A Long Tail

Scientists no longer debate the fact that greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels are changing Earth’s climate. Although this scientific consensus on climate change was established 20 years ago, it has never stopped influential politicians from calling climate change a hoax. Climate denial is a well-organized disinformation campaign to confuse the public in pursuit of a clear policy goal—namely, to delay climate mitigation.

The markers of conspiratorial cognition are universal, whether the subject is climate denial, antivaccination propaganda or conspiracies surrounding the origin of SARS-CoV-2. It is critical to help the media and the public identify those markers. Unlike the overwhelming evidence for climate change, however, a zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2 is likely but not yet conclusive. This is not a sign of nefarious activity and is, in fact, entirely unsurprising: It took 10 years to pin down the zoonotic source of SARS-CoV-1. The Zaire Ebola virus has never been isolated from bats, despite strong serological evidence that they are the likely reservoir.

Plausible routes for a lab origin do exist—but they differ from the engineering-based hypotheses that most lab-leak rhetoric relies on. The lab in Wuhan could be a relay point in a zoonotic chain in which a worker became infected while sampling in the field or being accidentally contaminated during an attempt to isolate the virus from a sample. Evidence for these possibilities may yet emerge and represents a legitimate line of inquiry that proponents of a natural origin and lab-leak theorists should be able to agree on. But support for those claims will not be found in self-sealing reasoning, quote mining of e-mails or baseless suggestions. Ironically the xenophobic instrumentalization of the lab-leak hypothesis may have made it harder for reasonable scientific voices to suggest and explore theories because so much time and effort has gone into containing the fallout from conspiratorial rhetoric.

Lessons from climate science show that failure to demarcate conspiratorial reasoning from scientific investigation results in public confusion, insufficient action from leadership, and the harassment of scientists. It even has the potential to impact research itself, as scientists are diverted into knocking back incorrect claims and, in the process, potentially ceding them more legitimacy than warranted.

We must anticipate that this type of dangerous distraction will continue. Scientists identified with COVID research are suffering abuse, including death threats. When the Omicron variant emerged, so did nonsensical conspiracy theories that it, too, was an escaped, human-altered virus, originating from the lab in South Africa that first reported it. One can only assume that further variants may likewise be blamed on whichever research lab is closest to the location of discovery. We are not doomed to keep repeating the mistakes of past intersections of science and conspiracy should we choose to learn from them instead.

*Editor’s Note (2/18/22): This sentence was edited after posting. It originally described U.S. Right to Know as an anti-GMO organization.