For countless Americans, there was a dull but persistent pain to prepandemic life: high-priced housing, nearly inaccessible health care, underresourced schools, wage stagnation and systemic inequality. It was a familiar ache, a kind of chronic hurt that people learned to live with simply because they had no other choice. Faced with threadbare safety nets and a cultural ethos championing nationalist myths of self-sufficiency, many people did what humans have always done in times of need: they sought emotional comfort and material aid from their family and friends. But when COVID-19 hit, relying on our immediate networks was not sufficient. Americans are gaslit into thinking that they are immeasurably strong, impervious to the challenges people in other countries face. In reality, our social and economic support systems are weak, and many people are made vulnerable by nearly any change in their capacity to earn a living. The fallout from the pandemic is an urgent call to strengthen our aid systems.

Anthropologists have long recognized that exceptionally high degrees of sociality, cooperation and communal care are hallmarks of humankind, traits that separate us from our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees and bonobos. This interdependence has been key to our success as a species. Viewed this way, we humans have an evolutionary mandate to be generous and take care of one another. But unlike early humans, who lived in comparatively small groups, we cannot just rely on our immediate family and friends for support. We must invest in national policies of communal care—policies that facilitate access to resources for people who need help—to a degree that is commensurate with the size and complexity of today’s globalized societies.

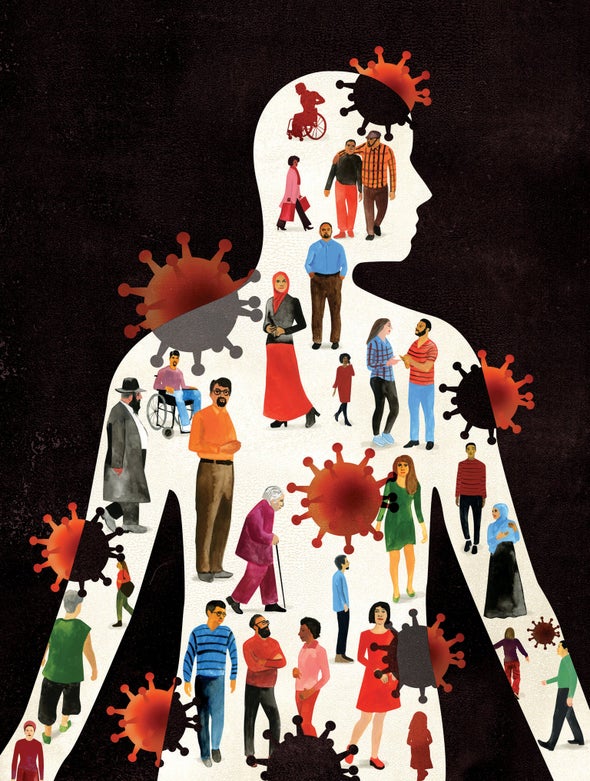

In a sense, the entanglement of our everyday lives made us all the more vulnerable to an airborne virus that demanded social isolation, blowing up the facade of normalcy in the spring of 2020. The new COVID normal, with its mask wearing, social distancing, lockdowns and closed schools, compelled us to abandon our most basic instincts and turn away from our closest friends and family. It rent the social fabric on which we all rely.

Infectious diseases present an unusual challenge: to combat them effectively, we must render aid appropriately and consistently at scale. This pandemic exposed the fragility and faults in each layer of our lives—from our innermost circle of family and friends to the nation state at the periphery—and the differential risk experienced by any individual’s core community. Communities that were already heavily invested in social safety nets with measures such as paid sick leave were able to lower COVID rates. Those invested in the ideology of self-sufficiency and individualism prolonged suffering and loss of life.

New Zealand (Aotearoa in Māori), a country with a long history of reckoning with its colonial past and building community, has been a standout success story in the pandemic. The government there countered COVID with nationwide stay-at-home orders, border controls, hygiene campaigns, accessible testing and contact tracing. The results were dramatic: 18 months into the pandemic, the country had seen only 27 COVID deaths. By late 2021, 90 percent of eligible citizens were fully vaccinated. Although new variants have been challenging these successes, the government remains deeply committed to care.

Similarly, Taiwan defied predictions that it would struggle with COVID infections like its neighbors in China by instituting a 14-day isolation policy for travelers entering the country, stepping up mask production, increasing border controls and deputizing quarantine officers who could help isolated citizens. By March 2021 there had been only 10 COVID deaths in a country of nearly 24 million people. Taiwan has fought each new wave of the pandemic with these tactics. Although we may call on our inner circle most frequently during our times of need, ultimately we must rely on local and national officials on the periphery of our lives to be exquisitely human—as the leaders of New Zealand and Taiwan have been—when they develop and enact health policies.

In the U.S., government support was inconsistent, and citizens struggled to work together to keep the virus at bay. The roots of these problems run deep. Since this country’s inception, the dominant ideologies here have encouraged not only individualism but also the dehumanization of certain groups, as evidenced by the enslavement of Black people and the displacement of Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands. This dehumanization continues today in the form of the bootstrap narrative—the myth that anyone can prosper if only they work hard enough—and in efforts to weaken relief programs for people who need help. As a result, even though we now know how the virus spreads and causes disease and we have effective vaccines against it, the death toll from COVID is higher in the U.S. than anywhere else.

There have been some success stories in the U.S.—they can be found in groups that have a fundamentally different ideological relationship to community interdependence. The Navajo Nation, which early on saw some of the highest rates of COVID-related illness and death, ran its own vaccine education campaigns and implemented in-house vaccine-distribution policies. It achieved far higher vaccination rates on its reservations than surrounding areas did. Tribal values that prioritize the group over the individual helped motivate members to get their shots. Unfortunately, in late 2021 the virus surged among the Navajo again, perhaps because of low vaccination rates in neighboring areas.

A microbe revealed the lie of rugged individualism. We are not self-sufficient and independent; we never have been. Our fates are bound together. Taking care of others is taking care of ourselves. With the arrival of the highly infectious Omicron variant, we are paying the price for not having developed strong policies early on and stuck to them. But that does not mean we should just give up the fight. Instead we need to redouble our efforts to provide care and resources to vulnerable community members. The emergence of each new COVID variant is an opportunity to reflect on what worked and what did not with the last one, whether locally or on the other side of the world. Committing ourselves to upholding our evolutionary mandate to help one another—not just the people we see every day but everyone, everywhere—is the only thing that will save us.