Nonfiction

Tending Our Musical Planet

What do we lose when the diversity of Earth’s noise is drowned out by humans?

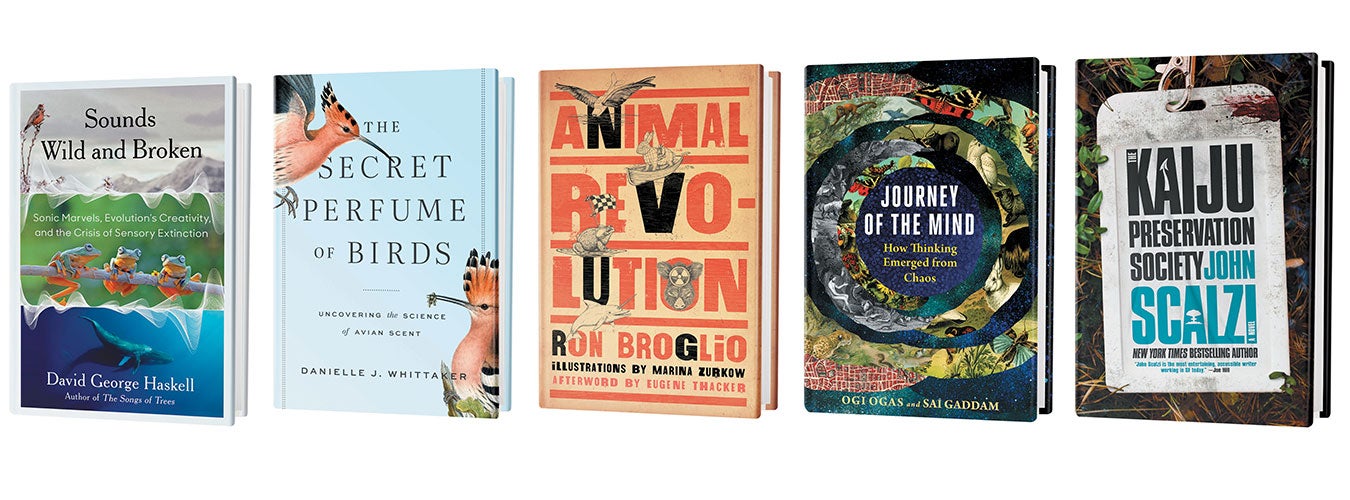

Sounds Wild and Broken: Sonic Marvels, Evolution’s Creativity, and the Crisis of Sensory Extinction

David George Haskell

Viking, 2022 ($29)

In the beginning was silence. The big bang made not a whimper, let alone a bang. That is because the universe was born in a sea of nothingness without the space and time where sound can exist. In the end, the universe will be reduced again to silence, either collapsed into a singularity or expanded into cold, flat uniformity. But now, suspended between the beginning and the end, Earth sings and rings and warbles: a musical planet, maybe the only one in the universe. As David George Haskell tells it in his captivating new book, Sounds Wild and Broken, it is astonishing good fortune—and a fearsome responsibility—to be given this music and the ears to hear it with.

At first stone, water, lightning and wind sang alone. After 3.5 billion years came the tremolo of cilia on the earliest cells. Eventually insects joined the swelling chorus, with “rasping mouthparts, wheezing air tubes, drumming abdomens, and wings shaped to crackle and snap as they fly.” Lacking a syrinx, dinosaurs could not exactly sing, but they still shook the Cretaceous forests with rubbing scales, snapping jaws, whip-cracking tails and a sound like the “strangled belch of ruddy ducks.” The asteroid that brought that cacophony to a cataclysmic end made room for the expansion of fluting birds. “In birdsong,” Haskell writes, “we hear the evolutionary legacy of renewal after great loss.” And what a renewal it was: roaring whales, bellowing elephants, tootling children and moaning freight trains. The whole Earth shimmered with sound.

The science stories in Sounds Wild and Broken offer one delight after another. What a joy to know that elephants can “hear” with special sensory pads on their feet, picking up the rumbling voices in the ground, and that birds in cities sing at pitches higher than those of their country cousins, choosing frequencies less masked by the city’s dull roar. Humans’ teeth, which once met in a predator’s vise, slid into an overbite as people turned to the softer foods that agriculture provided, shaping sounds such as “farm,” “vivid,” “fulvous” and “favorite.” We hear Earth’s sounds with ears that evolved from repurposed fish gill bone, sometimes in theaters designed to match the acoustic properties of forests. But why don’t worms sing? “Predation is a powerful silencer,” Haskell explains. “Animals whose lives are sedentary or slow and whose bodies lack weaponry are voiceless.”

Earth’s musical variety show testifies to the boundless creativity of evolution. As with improvisational jazz, order, narrative, complexity and beauty emerge from the interacting voices of Earth and its creatures. Here, in the bittern’s croak, in the turtle’s cluck and whine, in Miles Davis’s trumpet, is “evolution drunk on its own aesthetic energies.” Music returns us to direct experience—a time before language, before tools, before humans began to imagine themselves as separate from Earth’s community and outside its limits. We are enticed by beauty to listen to the sounds that remind us of our membership in the intricate, interactive orchestras.

As the book develops, it becomes clear that all this sonic science is not merely reporting. It is bearing witness to a terrible moral and ecological crisis. With lives powered by sequential explosions of gas and oil, humans make deafening noise. In our industrial empires, we are constantly assaulted by whirring tires, booming woofers, pounding engines and “a smeared canopy of airline noise.” The burden of noise pollution in cities is unjustly distributed, reinforcing race, class and gender inequities. The cacophonies indirectly and directly harm animals, of course, interfering with their reproductive patterns, reducing their habitats, fragmenting their communities and sometimes killing them outright. Haskell cites the U.S. Navy’s high-intensity sonar blasts, which panic whales: “Sound bleeds them to death from within.”

Reckless human enterprise is killing Earth’s wild songmakers at alarming rates, using poisons, bulldozers, forest-clearing fires and industrial-scale pillage of prey species. Readers who are at least 50 years old live in a world that is less than half as song-graced as when they were born. In that half a century, a third of North American songbirds have disappeared. Ninety percent of large fish are gone. Sixty percent of bellowing, squeaking mammals are extinct. All lost, in our lifetimes, on our watch.

What do we lose when we lose their songs? Listening to the song stories of other species can make us better members of life’s community, Haskell argues. They signal interdependence and resilience, deep kinship, shared beginnings and likely a shared fate. So they are the “foundations not only of delight,” he writes, “but of wise ethical discernment.”—Kathleen Dean Moore

Secrets of Bird Scent

A delightfully meandering account of a scientist’s curiosities

The Secret Perfume of Birds: Uncovering the Science of Avian Scent

Danielle J. Whittaker

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022 ($27.95)

Vultures and albatrosses find food using scent cues. Scent influences the mating behaviors of dark-eyed juncos. But when a scientist offhandedly told Danielle J. Whittaker that “birds can’t smell,” she discovered that most ornithology textbooks rarely mention avian olfaction and that this misconception was a common one. The realization changed the course of her life.

Unexpected changes are a regular occurrence for Whittaker, who has “never been particularly good at long-term planning.” In The Secret Perfume of Birds, Whittaker humorously recounts her own journey from office worker to primatology Ph.D. student to postdoc studying bird behavior to Roller-Derbying managing director of a National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center. One constant throughout the book is that things rarely happen as she expects them to, at times making her question everything she already knows.

After all, the study of avian olfaction is not straightforward. Birds daily cover their feathers in a substance called preen oil taken from a gland at the base of their tail. This oil contains odorous compounds— in the case of the dark-eyed junco, it smells like leaf litter and soil. Studying how this odor arises and its purpose in bird behavior combines the chemistry of smelly compounds, the biology of bacteria and even the genetics of human immune systems. In turn, scientists study this topic with a funhouse of experiments that involve capturing juncos in the Appalachians, sequencing DNA and surveying human women after they smell men’s worn T-shirts. Most of these experiments, in Whittaker’s view, have yielded as many questions as answers.

Though not a birder herself, Whittaker presents a new lens for bird lovers to view common species, and she had me wondering what some of my favorite birds smell like. But the book’s greatest success is how it depicts the reality of doing science. Experiments are difficult and do not always return clean answers. Scientists carry biases that can influence their results; for example, focusing on the stereotypically flashier male birds instead of the females can lead researchers to overlook important details. It takes a diverse group of perspectives—and the humility to reconsider our biases—to truly understand our world.—Ryan Mandelbaum

In Brief

Animal Revolution

by Ron Broglio

University of Minnesota Press, 2022 ($88)

In a chapter appropriately entitled “Manifesto,” English professor Ron Broglio begins his book of speculative nonfiction by proclaiming that the animal revolution, while it “will not be televised, mediated, or co-opted by our representation systems,” is nonetheless afoot. The following chapters present a compelling argument that pairs “untold incidents of animals in revolt” with theoretical frameworks that reveal their revolutionary power: Kantian subjectivism explicates the hordes of jellyfish that choke nuclear reactors, Derridean radical hospitality unpacks the sheep that commando roll over cattle grates. Broglio calls for all comrades to join the revolution. —Dana Dunham

Journey of the Mind: How Thinking Emerged from Chaos

by Ogi Ogas and Sai Gaddam

W. W. Norton, 2022 ($30)

Questions of consciousness often veer into philosophical territory that cannot be resolved, let alone approached by science. Journey of the Mind is a more unusual take. The co-authors’ backgrounds in computational neuroscience and machine learning inform their premise that behaviors can be broken down into modules of sensors and doers in the same way proteins are made of peptides and amino acids. The stars of the book are its illustrated diagrams of minds, beginning with “Archie” the haloarcheon and progressing to “Captain Buzz” the fruit fly and eventually to frogs, monkeys and humans. —Maggie Brenner

The Kaiju Preservation Society

by John Scalzi

Tor, 2022 ($26.99)

John Scalzi’s stand-alone adventure novel is a fun throwback to Michael Crichton’s 1990s sci-fi thrillers. When the first COVID wave hits New York City, a food-delivery driver named Jamie Gray joins a team of scientists at a secret facility in Greenland, where they travel to an alternative version of Earth populated by mountain-sized creatures called Kaiju, like those familiar from Japanese films. But other people with less scientific goals have found their way there as well. In an author’s note, Scalzi describes the book as a “pop song,” and he’s right—there are no cerebral messages about animal rights or nuclear proliferation. Written with the brisk pace of a screenplay, it’s as quippy as a Marvel movie and as awe-inspiring as Jurassic Park. —Adam Morgan