Human societies are constantly rearranging themselves, causing profound disruptions in our social lives. The industrial revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries fragmented communities as people moved for work, the decay of empires in the early 20th century reconfigured nations and national identities, and the Great Depression of the 1930s shattered people’s economic security and future prospects. But we are now in what is perhaps a time of unprecedented uncertainty. The early 21st century is characterized by rapid and overwhelming change: globalization, immigration, technological revolution, unlimited access to information, sociopolitical volatility, the automation of work and a warming climate.

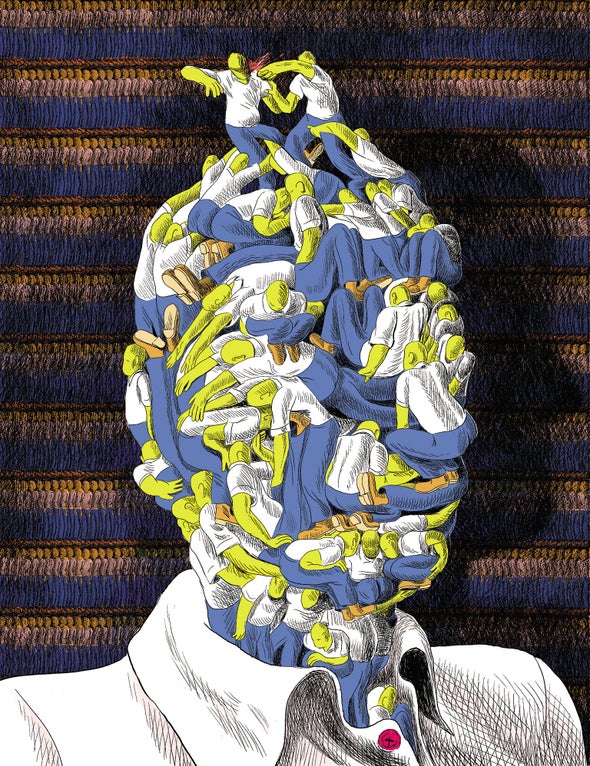

People need to have a firm sense of identity and of their place in the world, and for many the pace and magnitude of such change can be alienating. This is because our sense of self is a fundamental organizing principle for our own perceptions, feelings, attitudes and actions. Typically it is anchored in our close interpersonal relationships, such as with our friends, family and partners, and in the variety of social groups and categories that we belong to and identify with—our nationality, religion, ethnicity, profession. It allows us to predict with some confidence how others will view us and treat us.

Imagine navigating all the situations and people we encounter in day-to-day life while continually feeling uncertain about who we are, how to behave and how social interactions will unfold. We would feel disorientated, anxious, stressed, cognitively depleted, and lacking agency and control. This self-uncertainty can, in fact, be experienced as an exciting challenge if we feel we have the material, social and psychological resources to resolve it. If we feel we do not have these resources, however, it can be experienced as a highly aversive threat to us and our place in the world.

Generally, self-uncertainty is a sensation that people are motivated to reduce. When people are increasingly unsure about who they are and how they fit into this rapidly changing landscape, it can be—and indeed has become—a real problem for society. People are supporting and enabling authoritarian leaders, flocking to ideologies and worldviews that promote and celebrate the myth of a glorious past. Fearful of those who are different from them, they seek homogeneity and become intoxicated by the freedom to access only information that confirms who they are or who they would like to be. As a result, global populism is on the rise.

Seeking Social Identity

One powerful source of identity resides in social groups. They can be highly effective at reducing a person’s self-uncertainty—particularly if such groups are distinctive and have members who share a sense of interdependence.

Groups play this central role in anchoring who we are because they are social categories, and research shows that social categorization is ubiquitous. A person categorizes others as either “in-group” or “out-group” members. They assign the group’s attributes and social standing to those others, thereby constructing a subjective world where groups are internally homogeneous and the differences between groups are exaggerated and polarized in an ethnocentric manner. And because we also categorize ourselves, we internalize shared in-group-defining attributes as part of who we are. To build social identity, we psychologically surround ourselves with those who are like us.

This psychological process that causes people to identify with groups and behave as group members is called social categorization. It anchors and crystallizes our sense of self by assigning us an identity that prescribes how we should behave, what we should think and how we should make sense of the world. It also makes interaction predictable, allows us to anticipate how people will treat and think about us, and furnishes consensual identity confirmation: people like us—the in-group members—validate who we are.

This self-uncertainty social-identity dynamic is not in itself a bad thing. It enables the collective organization that lies at the heart of human society. Human achievements that require the coordination of many in the service of common goals cannot be achieved by individuals on their own. Yet this dynamic becomes a problem when the sense of self-uncertainty and identity threat is acute, enduring and all-encompassing. People then experience an overwhelming need for identity—and not just any identities but ones that are well equipped to resolve those disorienting, even scary, feelings.

Reducing Uncertainty through Group Membership

Some features of groups and social identities are especially well suited to reducing self-uncertainty. Most important, groups need to be polarized from other groups and have unambiguous boundaries that distinguish between those who are “in” and those who are “out.” Internally they need to be clearly structured, typically in a hierarchical way. These features make the group cohesive and homogeneous, such that members are interdependent and of one mind in sharing a common fate.

Diversity and dissent reinstate uncertainty and are therefore avoided. When these facets do occur, individuals and the group as a whole react decisively and harshly, creating an atmosphere of suspicion that lays the ground for persecution of alleged deviants. It breeds an opportunity for personal dislikes and vendettas to escalate under the guise of protecting cohesion.

That members are accepted and trusted fully is important not only for the group but also for the members themselves. After all, they desperately want to be included so that their identity is validated and their uncertainty thus reduced. Prospective and new members—and those who suspect they are viewed with suspicion or are uncertain about whether they are fully accepted—will go to extremes on behalf of the group to prove their membership credentials and loyalty. These individuals are vulnerable to zealotry and radicalization. Neo-Nazis and white supremacists who publicly engage in violent acts of terrorism and racial hatred are one example of this extremism.

The social identity embodied by such groups also needs to be uncomplicated so that it can be taken at face value as “the truth.” Subtlety and nuance are anathema because they are an impediment to uncertainty reduction. Clarity on where the group stands allows its members to know how they should think and feel—as well as behave. Such identities are bolstered by having a strong ideology that identifies distasteful and morally bankrupt out-groups who can be demonized and cast in the role of “enemy.” Conspiracy theories thrive in this environment because they establish these out-groups as agents of historical victimization by the in-group.

How Uncertainty Breeds Populism

If self-uncertainty motivates people to identify with a group and internalize that identity as a key part of who they are, they need to be confident that they know exactly what their group’s identity is. When you need what you consider to be reliable and trusted sources of identity information, where do you turn? The first port of call is whoever you believe is consensually viewed by the group as its leadership—typically someone whose leadership position is also formalized.

Recent research on how self-uncertainty affects the type of leaders that individuals prefer paints a potentially alarming picture. People just need someone to tell them what to do—and ideally those directives are coming from someone whom they can trust as “one of us.” Self-uncertain people have also been shown to prefer leaders who are assertive and authoritarian, even autocratic, and who deliver a simple, black-and-white, affirmational message about “who we are” rather than a more open, nuanced and textured identity message.

Perhaps most troubling is that self-uncertainty can enable and build support for leaders who possess the so-called Dark Triad personality attributes: Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy. Self-uncertainty, in other words, seems to fuel populism.

Another source of identity information is “people like you” who you feel embody the group’s identity and see the world in the same way as you do. These can be people with whom you interact face-to-face or as friends, or they can be sources of information such as radio and television channels, particularly news outlets, that you watch. But nowadays these sources are overwhelmingly information and influence nodes on the Internet, such as Web sites, social media, Twitter feeds, podcasts, and so forth.

The Web is an ideal place to decrease the discomfort of self-uncertainty because it provides nonstop access to unlimited information that is often cherry-picked by individuals themselves and algorithms that do it discreetly. Therefore, people are accessing only identity-confirming information. Confirmation bias, a powerful and universal human bias that is especially strong under uncertainty, separates information and identity universes that fragment and polarize society. Online, people can easily seek out groups that may not be readily available in their physical lives.

The Internet further empowers confirmation bias under uncertainty because people want to be surrounded by those who think alike so that their identities and worldview are continuously confirmed. The contours of “truth” then get mapped onto these self-contained social-identity universes. In this scenario, there are no absolute truths and no motivation to seriously explore and incorporate alternative viewpoints because that would be kryptonite to social identity’s power to reduce self-uncertainty. This dynamic helps to explain why people dwell in increasingly homogeneous echo chambers that confirm their identity.