In the spring of 2017 I was serendipitously invited to what initially seemed to be the wrong scientific meeting. The invitation came thirdhand, and the details were murky but intriguing. I took a car to a train to a downtown hotel where I wound my way through a series of conference rooms before a sign on a door made it clear that something was terribly wrong. It said, “MAPS Phase 3 meeting.”

Phase 3 is the final step in clinical drug testing before approval. It is conducted with a large group of study volunteers to make sure a drug is safe and effective. The endless meetings surrounding these trials typically involve months of vetting, confidentiality agreements and contracts; they are not to be crashed by wayward scientists with thirdhand invitations, and I immediately felt out of place.

Before I could retreat, someone emerged from the conference room and looked me over intensely. She asked me to explain myself, and then, to my surprise, she turned to staff at the check-in table and said, “Get her a name tag. We’ll figure this out later.” By the end of the day I had come to know this powerhouse by name: Berra Yazar-Klosinski, chief scientific officer at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). My background in behavioral pharmacology and clinical trials seemed to pique her attention, and by the end of the meeting I had committed to working with her on the phase 3 program that would assess the efficacy and safety of MDMA—known recreationally as Molly or Ecstasy—for severe PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD is characterized by the reliving of unwelcome traumatic memories, and according to the National Center for PTSD, upward of 15 million people in the U.S. suffer from this debilitating condition in any given year.

MDMA, short for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, is an amphetaminelike compound that was first developed by European pharmaceutical giant Merck in 1912 as part of a research program on blood-clotting agents. Shelved for years, it was resynthesized by chemist Alexander Shulgin in the 1970s and immortalized in his book PiHKAL, which contains a recipe for MDMA. Not long after, Shulgin shared the compound with a friend, psychologist Leo Zeff in Oakland, Calif. Zeff and his colleagues began to use MDMA in conjunction with psychotherapy in private practice and noted that their patients were better able to confront emotionally evocative and distressing memories. Within an hour of ingesting the compound, patients could set aside their fears and face recollections of shame and trauma.

Right on the heels of this discovery, however, MDMA stepped out of the psychotherapist’s office and barreled into general circulation, becoming one of the most used substances for recreational purposes of the 1980s. In 1985 the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) classified MDMA as a Schedule I substance, making its possession a crime punishable by up to 15 years in prison. The National Institutes of Health subsequently spent two decades funding research that suggested MDMA is neurotoxic and often lethal.

Animal studies showed that MDMA induces a massive release of the neurotransmitter serotonin, a signaling molecule that is an important regulator of mood and affect. Once released into synapses (the small gaps between neurons across which chemical signals pass), serotonin acts on receptors on nearby neurons to improve one’s emotional state. Not only does MDMA cause a serotonin surge, it also prevents the signaling molecule from being reabsorbed into the neurons that secreted it, allowing serotonin to sit in the synapse and signal for longer than usual. This serotonin surge also induces the release of the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin from a brain region called the hypothalamus. Both of these hormones are thought to foster interpersonal bonding and feelings of closeness.

These early studies indicated that MDMA can promote long-lasting restructuring of serotonin-containing nerve fibers, but they also suggested that such changes occurred only at high doses and were reversible over time. Then along came George Ricaurte, a neurologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who made a name for himself by touting the alleged neurotoxic and lethal effects of MDMA. Ricaurte claimed that “even one dose of MDMA can lead to permanent brain damage.” His findings, proclaiming that MDMA could ravage the brain and leave nothing but damaged fibers in its wake, were published in the journal Science and used time and again by the National Institute on Drug Abuse to support the war on drugs.

These data were later retracted after it was revealed that amphetamine, not MDMA, had caused the reported neurotoxicity. But it has taken us years to get beyond sensationalistic antidrug propaganda posters in which phrases such as “This is your brain on Ecstasy” were splashed atop artificially colored brain scans, making it look as if MDMA, as one DEA official put it, “turns your brain into Swiss cheese.”

More recent animal data indicate that MDMA helps to extinguish memories of fearful experiences and impairs the reactivation of traumatic memories in rodents. These studies have shown that even the notoriously solitary octopus develops a penchant for hugging under the influence of the compound. Perhaps most intriguing are animal data that demonstrate that MDMA, coupled with oxytocin release, may reinitiate a “critical period” similar to those that occur during the social and emotional learning of childhood. This reopening appears to create a fluid state in which the painfully negative feelings attached to deeply traumatic memories can be processed and attenuated.

Similarly, recent human data have shown that MDMA increases cooperative behavior when subjects play a game with someone trustworthy and may help emotional recovery when their trust is compromised. If MDMA can truly soften the grip of negative memories, how do we take the next step toward evaluating and developing it as a potential therapeutic drug for veterans, victims of physical and sexual assault, and survivors of natural disasters who experience PTSD?

Getting to Yes

After the MAPS meeting, I sat in my car and contemplated the tremendous hurdles involved in a phase 3 clinical trial. I had explained to Yazar-Klosinski that although I had acquired a fair amount of experience with phase 2 testing, I had never conducted a phase 3 trial, and it seemed foolishly shortsighted to think that sheer determination alone would enable me to tackle the complications that would inevitably arise. She was undaunted, but I was terrified.

Schedule I status is a bane for drug developers. According to the U.S. Controlled Substances Act, Schedule I substances by definition have no medical use, no accepted safety data and a high potential for misuse, which means there is typically no federal funding to study such compounds as potential therapeutics.

Given the regulatory obstacles, creating a research program for a Schedule I substance is a difficult and time-consuming process. Such compounds are highly restricted, and permission must be obtained from the DEA to allow them to be stored at a research facility and dispensed to subjects. To make matters worse, the Controlled Substance Analogue Enforcement Act of 1986 states that all compounds that are “substantially similar” to Schedule I compounds are also illegal, so there is no way to even approximate the effects of a drug such as MDMA in the laboratory without risking criminal charges.

To work with a Schedule I substance, one first needs to apply for a DEA license that lists each compound involved, the amount that will be used for each experiment, where and how the compounds will be stored, who will have access to the space, what security measures will protect them, and what record-keeping procedure and audit trail will be used to track them. There are annual fees to be paid and amendments to file with every change. This arduous process discourages all but the most resolute of investigators. There is also no clearly delineated process for reclassifying scheduled drugs, so even if there were enough data to demonstrate that a compound such as MDMA has a true pharmaceutical effect and a low potential for abuse, there is no obvious path toward assigning them a new classification as Schedule II, III or IV substances.

Once the DEA has signed off on Schedule I access, a similarly elaborate and time-consuming process is involved in getting approval from the Food and Drug Administration to give a Schedule I substance to humans. The first step is to submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the appropriate division within the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. This application must contain virtually everything that is known about the drug to date, including data from animal pharmacology and toxicology studies, any results from human experiments, a manufacturing plan to assuage concerns about purity and supply, and other details about the clinical trial protocol and even the investigators involved. The FDA policy is to reply to IND applications within 30 days, but if for any reason the agency does not feel comfortable granting approval, a project can be placed on an indefinite clinical hold, which to clinical researchers is considered the kiss of death.

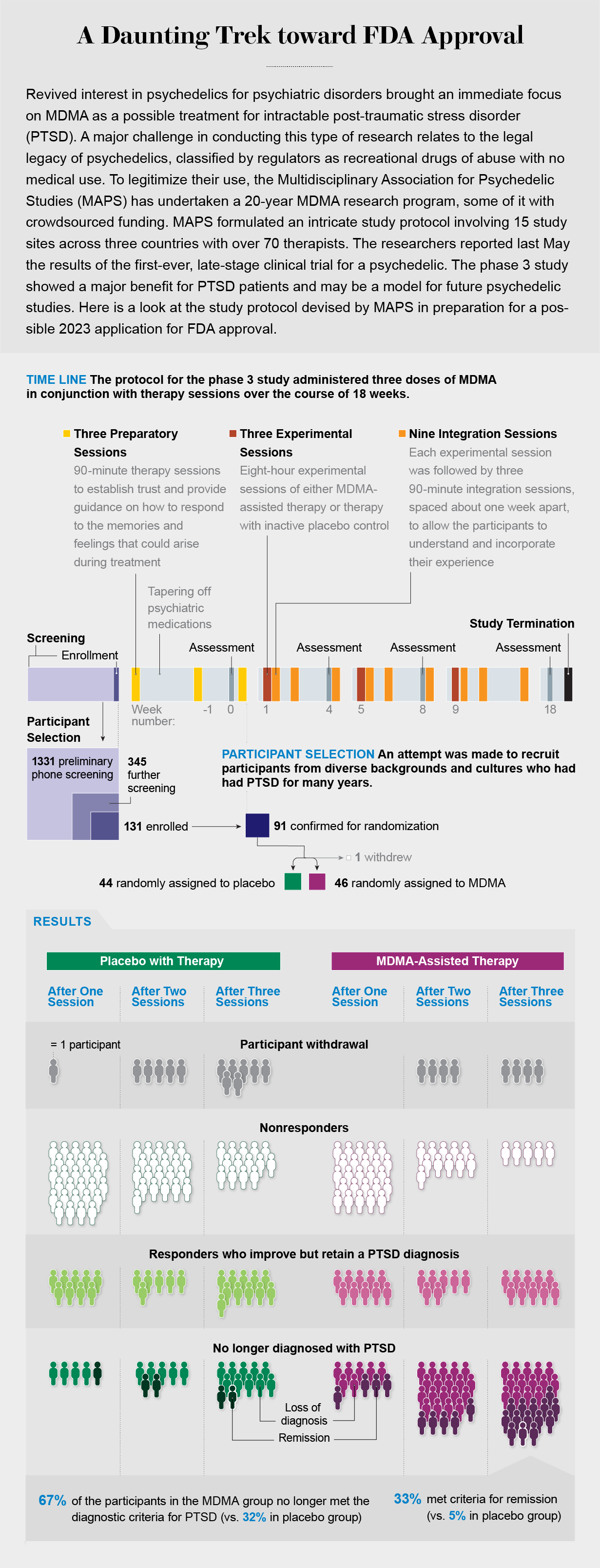

Our research team was able to take advantage of a Special Protocol Assessment (SPA), a new mechanism by which the FDA approval process can be made faster and more transparent. The SPA allows a sponsor—in this case, MAPS—to reach an agreement with the FDA on the study design, including a specific number of subjects, dosing, analysis plan and outcome measures. Because face time with the FDA is a rare and valuable commodity, it was quite a boon to receive a coveted SPA in 2017—and even better to be awarded Breakthrough Therapy Status the same year. The breakthrough designation grants expanded access to agency support and guidance and allows fast-tracking through the approval process if a drug is being developed to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

Even once all the appropriate regulatory and compliance issues have been tackled, there is still the matter of manufacturing the compound. For clinical trials, this step must be performed in a “good manufacturing practices” (GMP)-certified laboratory. GMP ensures that production is consistent and conducted in a clean environment and meets FDA-prescribed quality standards. Although the process was seemingly straightforward, it took several tries to identify a GMP-certified lab able to reliably generate a pure compound. MDMA is also a painfully static molecule and tends to stick to everything it should not, meaning that it took practice for the GMP facility to successfully encapsulate the drug.

Crowdfunding a Clinical Trial

Bringing any new drug to market is difficult, but for psychedelics the process has been downright daunting. The first study of MDMA for PTSD, also funded by MAPS, obtained FDA approval in 2001, but recruitment of research participants for phase 3 did not begin until November 2018. Even an SPA and Breakthrough Therapy Status mean nothing without research funding. It costs an average of $985 million to bring a new drug to market. Because federal agencies typically do not support clinical research on Schedule I compounds, most funding for MDMA research to date has come through philanthropy and even some crowdfunding. (An aside: if someone had suggested to me 10 years ago that anyone, anywhere, would ever be conducting a phase 3 drug trial funded by crowdsourcing, I would have laughed them out of the room.)

The financial situation may soon improve, however. Just a few years ago, when psychedelics again started being tested in human trials, pharmaceutical companies were not exactly banging down the door to join the club. But in the past year enthusiasm has been dialed up, and psychedelic start-up companies now abound. With any luck, this funding and interest will help MAPS propel the first application for approval of MDMA for clinical use through the FDA within the next two years.

Although more than half a dozen phase 2 studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of MDMA for PTSD, early trials often fail to accurately predict the outcome of the larger, multisite phase 3 trials that follow. In the case of MDMA, we have been lucky. At 15 study sites across three countries, working with more than 70 different therapists and with study participants with childhood trauma, depression and a treatment-resistant subtype of PTSD, we have obtained incredibly promising results.

Phase 3 study participants receiving MDMA-assisted therapy showed a greater reduction in PTSD symptoms and functional impairment than participants receiving placebo plus therapy. In addition, their symptoms of depression plummeted. By the end of the study more than 67 percent of the participants in the MDMA group no longer met criteria for PTSD. An additional 21 percent had a clinically meaningful response—in other words, a lessening of anxiety, depression, vigilant mental states, and emotional flatness.

And although there had been concern that administering any new medication to people with suicidal ideation could worsen their problems, MDMA-assisted therapy did not increase measures of suicidal thinking or behavior. MDMA also did not demonstrate any measurable misuse potential (which should compel us to reconsider the reasoning behind the war on drugs and scare tactics of the 1990s).

Yet despite these encouraging findings, it would be irresponsible to expect similarly impressive outcomes for MDMA in less clinically controlled situations and more heterogeneous populations. The success of psychedelic medications depends on tight control of variables such as the experience of the therapist team, the environment or setting in which the therapeutic is administered, and the amount of time participants spend integrating what they learn during the psychedelic session. Our work has no bearing, though, on recreational use of MDMA, which typically occurs in settings dramatically different from those of fastidiously planned clinical experiments and relies on street drugs that are often cut with all kinds of adulterants.

We are currently collecting long-term follow-up data from the phase 3 study. One important question is how long the therapeutic effects of MDMA and other psychedelics might last. Clearly, these compounds differ from drugs such as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), which must be administered daily, usually for years and sometimes indefinitely. We do not yet know whether our participants will have to return every couple of years for additional MDMA-assisted therapy. Although early clinical studies suggest that the therapeutic effects of psychedelics can be quite long-lasting, we also do not yet know whether there are subsets of our clinical population for whom the effects are particularly durable and others for whom additional dosing sessions or integration work will be needed.

MDMA is an experiential medicine, so its therapeutic effects are influenced by the setting in which it is administered. This is a key distinction from other medications. I would not expect a blood thinner to have certain effects if I took it in my parents’ living room versus in my neighbor’s kitchen. I would not expect it to work differently depending on my mood.

Psychedelics are undeniably different. They are dependent on frame of mind and environment. For this reason, it is essential to educate participants on the potential effects of the compound before consumption. The treatment setting must be thoughtfully constructed to provide the right amount of support and protection. It is even more critical that participants be guided through the experience by trained facilitators—often doctors or psychologists with special training—who know how to gently shift and shape the experience and to help them process the many facets of trauma that will arise. Additionally, if, as the animal data suggest, the MDMA-induced reopening of a critical period could last for several weeks, every effort should be made to use that time to heal, learn and grow.

Our study participants came from a multitude of backgrounds and cultures, but all had been diagnosed with severe PTSD and had been suffering from it for, on average, more than a decade. Many of them were considered treatment-resistant, having tried other PTSD therapies and therapeutics to no avail. More than 90 percent of them reported depression that accompanied their trauma, as well as suicidal thoughts.

Participants typically underwent three preparatory sessions with their therapy team before embarking on their three all-day experimental sessions. These prep sessions helped us set expectations for treatment and described what the subjects should anticipate if they were among those who received MDMA. Because this was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, these sessions also gave us a chance to explain what it might feel like to receive a placebo and how to manage disappointment about it. (Although it can be nearly impossible to fully mask the effects of a psychedelic, some of our participants guessed that they had received MDMA when in fact they had received placebo, and some guessed that they had received a placebo when they had received MDMA.)

Preparatory sessions were followed by an experimental session. Participants reclined on a sofa in a comfortable, dimly lit room and received a blister pack of study drug and a glass of water to begin their journey. Later came three integration sessions in which facilitators worked with participants to further untangle the trauma laid bare during the experimental session.

There is still much to learn about the neurobiological mechanisms of action of MDMA therapy, but it typically enables participants to engage in active, open discussions about their trauma without becoming emotionally overwhelmed—a major challenge to those suffering from PTSD. They frequently discuss their traumatic experiences with tremendous self-compassion, which some of our therapists speculate is the key to their eventual liberation from their burdens. By the end of the study participants are sometimes noticeably changed in physical appearance. They stand up straighter, they meet our eyes and they even smile.

Which Is It?

One of the biggest unanswered questions as we develop psychedelic medications is whether the subjective “psychedelic” experience is necessary for the therapeutic actions or is an irrelevant side effect that should be engineered away to make the treatment process faster and more marketable. Indeed, drug companies intent on developing “nonpsychedelic” psychedelics (those that have no psychoactive or hallucinogenic effects) have suddenly come out of the woodwork. Yet given the myriad data suggesting that the intensity of the mystical experience correlates with therapeutic improvement—and subjective reports espousing the beneficial impact of a psychedelic epiphany on years of negative thinking—it seems prudent to continue to focus on truly psychedelic compounds.

In addition to PTSD, data support the use of MDMA for depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and alcohol and drug use disorders. DEA rescheduling could reduce the barrier to clinical assessment of MDMA for these and other indications. Even after DEA and FDA approval of MDMA for PTSD has been obtained, however, a slew of tasks must be completed before the drug can reach the market. There should be a pipeline for training and credentialing psychedelic facilitators and for generating a system of clinics through which they can practice. Drug developers will need to develop a risk-evaluation and mitigation strategy and submit it to the FDA for approval—this step is to confirm that clinical use of MDMA carries no unchecked risks or side effects—and they will have to design a treatment cost structure to encourage HMOs and insurance providers to cover the expenses.

I first read about the potential therapeutic effects of psychedelics for anxiety and addiction in college, and by the time I entered graduate school I was convinced that understanding these compounds would lead to better treatments for a variety of mental health disorders. Because we were never able to obtain access to psychedelics for lab testing, we instead focused on separating out the various components of their biochemical activity (typically termed reverse engineering).

Most psychedelics have multiple pharmacological targets, and it is possible to tease them apart and test them one step at a time with more easily accessible drugs. For example, if a psychedelic induces the release of serotonin and oxytocin, we can try modifying behavior with an SSRI or oxytocin. If it acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist, which blocks the signaling molecule glutamate, we can use an NMDA receptor antagonist such as ketamine. Many of us have spent decades investigating the neural mechanisms and behavioral effects of potential therapeutics in this way based on our knowledge of the biochemistry of psychedelics. Although the fields of neuroscience and behavioral pharmacology have come quite a long way in terms of understanding behaviors such as anxiety, fear, substance craving and impulsivity, we have still fallen far short of generating a panacea for the suffering caused by these conditions. Perhaps it is time to take a different tack.

More than 50 years ago, after a decade of growing civil unrest and in response to the spreading recreational use of psychedelics, the pendulum of acceptance swung sharply. The turmoil and fear of the 1970s propelled a national agenda of regulation and criminalization. Half a century later the pendulum has swung again, and we find ourselves considering anew the medical value of psychedelic drugs. In addition to several dozen new studies on the effects of MDMA, there are now ongoing clinical trials for several other psychedelics, including psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca and ibogaine.

As enlightened as this new direction might feel, we must take care to ensure that the zeal of the converted does not color our decision-making. We need to take the time to thoroughly investigate these powerful compounds—to understand both their benefits and their shortcomings. Without scientific rigor, the pendulum could swing again. “Nothing to excess” and “the dose makes the poison” are the adages I hear time and again. The road to MDMA approval as the first medical psychedelic may still be long and bumpy, but if the enthusiasm and drive I encountered in that hotel conference room nearly five years ago are any indication of things to come, then I believe we are steadily heading in the right direction.