A thousand years ago the islands that today form New Zealand were riotously wild. Birds, reptiles and invertebrates flourished in lush forests hundreds of miles from any other landmass. Māori settlers in the 1200s brought Polynesian rats for food, and together the humans and the rodents began to shift the ecological balance. Native species started to go extinct.

Enter European ships, bearing new carnivores: more aggressive rat species, plus mice, stoats, and others. These ground-based predators hunted differently from the falcons and other aerial threats New Zealand wildlife had evolved with. Native birds that slept in burrows made easy prey for prowling mammals. Invasive predator populations exploded, devastating native wildlife.

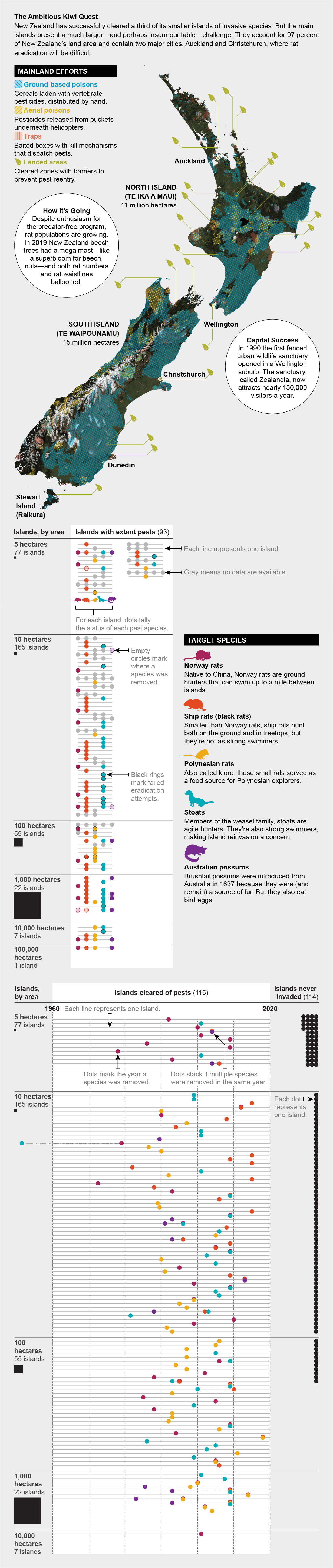

But in the past 60 years humans have intervened to help old New Zealand ecosystems claw their way back. First, a single five-acre (two-hectare) islet called Maria Island (Ruapuke in Māori) was declared rat-free by ecologists in 1964, five years after volunteers set poisoned bait. It was a special case. The white-faced storm petrels at risk there were especially charismatic—they appear to walk on water—and easily gained public support. The ample baiting effort also got particularly lucky with its placement, ecologists say. Nevertheless, the serendipitous success kicked off decades of eradication efforts.

Since then, New Zealand ecologists have cleared island after island of invasive pests. About two thirds of the country’s smaller islands are now pest-free, as are 27 fenced forest fragments on the main islands (which make up 97 percent of New Zealand’s land area). Native life surrounded by fence or sea is rebounding. And in 2016 the prime minister announced a first-of-its-kind nationwide goal: Predator-Free 2050.

The initiative aims to remove rats, stoats and possums from all New Zealand’s 600-plus islands by that year. “Those three animal predators are basically just eating our native wildlife out from under us,” says program director Brent Beaven.

Killing stoats and possums might startle some nature lovers, but University of Auckland ecologist James Russell describes the situation as an ecological trolley problem: “If we choose not to kill the mammals,” he says, “we’re essentially choosing to let the birds die.”

Russell describes the initiative as a broad social movement. “It’s not something that the government proposed,” he says. “The government adopted something for which there was a groundswell already.” In Predator-Free 2050, the government coordinates actions by universities, nonprofits, wildlife sanctuaries, habitat-rehabilitation programs, and people with traps in their backyards. These groups are removing the predators while developing better-targeted poisons, restoring native plant life, reintroducing native species and inventing new ways to keep predators out.

Predator-Free 2050 also relies on Māori tribes, says Tame Malcom, who works for the environmental nonprofit group Te Tira Whakamātaki: they have been trapping rats for centuries, and Māori partnership has increased the program’s effectiveness and reduced costs. “Our language is proving almost vital to ecological restoration efforts,” Malcolm adds, “because the names of places give a clue about what the place used to be like.” The location name Paekākā, for example, comes from “horizon” and a type of parrot, indicating the place was once rich with that species.

For everyone focused on eradication, the basic blueprint is the same: choose an island or sanctuary, intensively kill invasive animals, then monitor to make sure they stay away. But reality, of course, is more complex. Massey University conservation biologist Doug Armstrong, who heads the Oceania section of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s reintroduction specialist group, notes that not all native species take off quickly once an area has been cleared. Learning and catering to struggling species’ habitat needs will take time. And with their competition so helpfully removed, mice can balloon in number as they feast on native lizards and frogs.

Then there is cost. “Our standard eradication practices at the moment are $600 to $1,000 [NZD] a hectare, and we just can’t sustain that as a country,” Beaven says. Program leaders hope technology will help. Last year biologists finished sequencing all target species’ genomes, which could lead to targeted baits or gene-editing approaches akin to recent mosquito-control projects elsewhere. (New Zealanders, many of whom worked to ban genetically modified organisms in the early 2000s, are still debating whether to pursue gene editing.) Engineers are developing traps that identify species by their footsteps, and researchers are building drones to distribute bait and monitor large areas for reinfestation. The country’s innovations are already rippling outward: Armstrong says the bulk of international invasive species eradication efforts have New Zealanders somewhere at the helm.

But as researchers tackle the challenges of clearing invasive predators from an entire country, some ecologists question the initiative’s premise, even for somewhere as geographically isolated as New Zealand. Wayne Linklater, an environmental scientist at Sacramento State University, suggests fully removing invasive predators is unattainable. Instead he advocates for mitigation, such as protected breeding zones or a network of sanctuaries to conserve threatened species more effectively. Such tactics have met with success in Australia and South Africa.

Beaven, however, sees those approaches as stopgaps requiring constant human involvement. Eradication, he says, lets native flora and fauna truly thrive. That’s what program fieldworker Scott Sambell would like to see. A few times a year Sambell uses a rat-sniffing dog to monitor islands that have previously been cleared. His circuit includes some places that, like Maria Island/Ruapuke, have been pest-free for five decades. “You get into these areas, and you feel like a stranger,” he says. “This is the birds’ domain. And it’s awesome.”