NONFICTION

Life, Linked

A reverse journey through geologic time shows the interconnectedness of Earth’s species

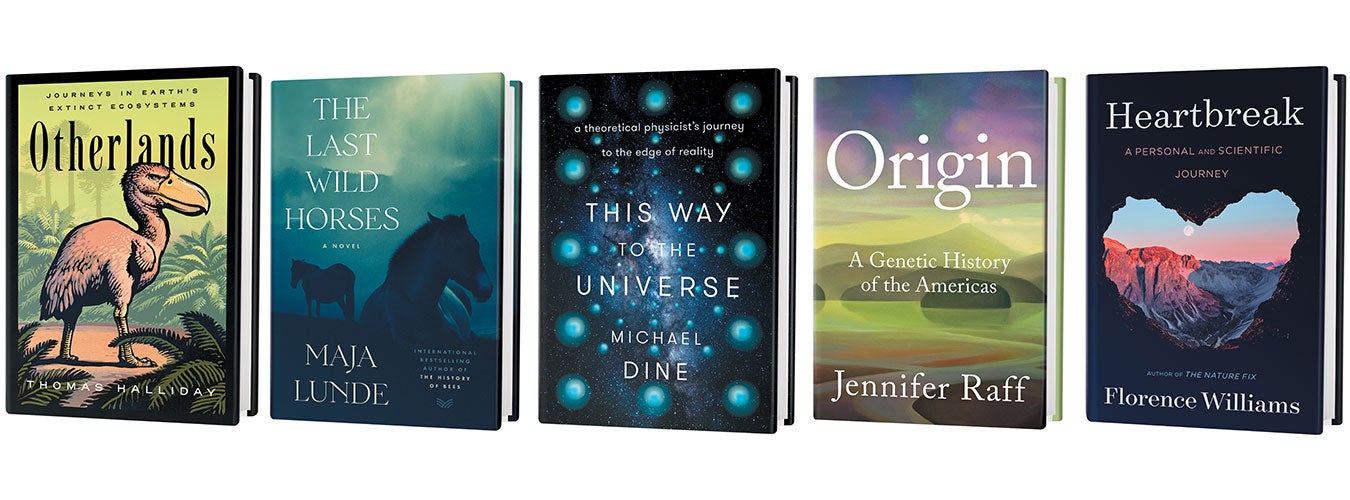

Otherlands: Journeys in Earth’s Extinct Ecosystems

by Thomas Halliday

Random House, 2022 ($28.99)

As a teenager, I was obsessed with dinosaurs, but I had little aptitude for what came before them. I couldn’t make sense of what John McPhee, in that most glorious line of geopoetry, called “deep time.” Planet Earth is 4.5 billion years old, and life has been around for about 90 percent of it. When T. rex stalked its prey, every trilobite that ever fossilized was already in the ground. Every Brontosaurus, too. The time spans seem inconceivable, yesterday’s worlds far too distant from our own. Then, a book made it click: this was Richard Fortey’s 1997 Life, which I devoured around the time I started studying geology in college. It was hard science, but it read like a novel, and it made the murky depths of prehistory into a riotous story.

Fortey wrote from his perch at the Natural History Museum in London, as one of the world’s most respected and experienced paleontologists, the letters F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society) trailing his name. A quarter of a century later Fortey’s Life has a worthy successor in Thomas Halliday’s Otherlands. Writing with gusto and bravado, Halliday is part of our generation of 30-something paleontologists, not long out of grad school, putting a millennial spin on popular science writing.

In a genre that can tend toward cookie-cutter sameness (another dinosaur encyclopedia?), Halliday has honed a unique voice. His approach is novel as well. Otherlands is a Benjamin Button tale, which begins in the present day and runs in reverse, the evolution of life in rewind. He structures the narrative through an ecological lens: Each major division of geologic time is given a single chapter, which is focused on a single lost ecosystem. As you read along, Earth gets weirder and weirder, the creatures more alien, more removed from the norms and comforts of today. Soon enough, you find yourself underwater 550 million years ago, in what is now Australia, where fish and whales and corals are nothing but a future fantasy, as blobs of primitive cells leave ghostly impressions on the seafloor.

Otherlands is a verbal feast. You feel like you are there on the Mammoth Steppe, some 20,000 years ago, as frigid winds blow off the glacial front. You sense fear in a band of human ancestors as they clamber up a tree, fleeing a python. You can taste the salty air over a Jurassic lagoon and commiserate with a gorgonopsian—a ghastly mammal predecessor—as a tumor presses down on its jaw.

Along the way, we learn astounding facts. Some trees that are alive today emerged from seeds while mammoths trudged through snow; reefs of sponges once stretched from Poland to Oklahoma. And we meet some sublime creatures. There’s Haikouichthys, one of the oldest fishes, “only a few centimeters long, shaped like a fallen leaf.” Even more ancient is Eoandromeda, probably one of the oldest animals (or maybe not), a “coiling helter-skelter, floating hypnotically” in the Precambrian oceans. My favorite, the official fossil of my home state of Illinois, is the mystifying Tully Monster, with its “segmented torpedo of a body” and a “hose of a vacuum cleaner” as a nose.

During this backwards journey across time, Halliday centers his tale on how species work together as ecosystems and food webs. Yes, dinosaurs and megafaunal mammals pop up throughout, but plants, bugs, mushrooms and deep-sea bacteria all get their due. The great calamities and transformations of prehistory are treated more like background; the end-Permian mass extinction—the closest complex life has ever come to annihilation—garners a single paragraph, and the origin of limbed tetrapods from finned fish takes all of four sentences. This keeps attention on the bigger picture, as Halliday shows that the same rules of energy flow have governed all ecosystems over time, linking that dream world of 550 million years ago to dinosaurs to our fragile Earth of today.

Otherlands is a book for people who like books. Chapters begin with verses and proverbs in many languages (original and translated), poetry and mythology are liberally quoted throughout, and fossils are described with comparisons to Gaudí’s architecture and L. S. Lowry’s paintings. In many ways, it is more literature than traditional popular science, which makes me wonder how it will connect with people who haven’t studied science (or poetry) since school.

Another new book on evolutionary history is more tailor-made for a general audience. A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth, written by Nature editor Henry Gee and published in late 2021, does what it promises. Punchy and breezy, his book reads like a bedtime story, the triumphs and cataclysms of life waltzing by at breakneck speed. Gee’s book is more appetizer, Halliday’s is more main course, and together they weave an evocative tapestry of what Earth and life have endured—which helps us understand where we are going next.—Steve Brusatte

FICTION

Interspecies Epic

Saving rare horses from calamities past and future

The Last Wild Horses: A Novel

Maja Lunde Translated by Diane Oatley

HarperVia, 2022 ($27.99)

Norwegian author Maja Lunde became an international sensation with The History of Bees, the first novel in what she is calling her “Climate Quartet.” The much anticipated third book in that series, The Last Wild Horses, is further evidence that some writers know how to spin a tale. The novel braids three time periods and places, all linked by the takhi, a rare wild horse species, and the humans devoted to saving them.

We start in 2064 in postapocalyptic Norway. Weather has become unpredictable, society has collapsed, and migrants move north by foot in search of food, infrastructure and clean water. But Eva and her 14-year-old daughter, Isa, have stayed put on their family's farm, trying to stay alive with their cows and chickens, as well as to protect the takhi that Eva's sister began sheltering years ago.

We then leap back to St. Petersburg in 1882, where a zoologist discovers that the long-presumed extinct takhi might still be living in the far reaches of Mongolia. He becomes consumed with how to capture some for the garden where he works.

Soon we are spinning forward in time again to meet Karin in Mongolia in 1992. Karin has been obsessed with the takhi since she first saw them as a child during the war in Germany. She has built a stable herd in a small village in France and is transporting them back to their native habitat in Mongolia with the hope that they can once again breed and survive in the wild.

In quixotic and propulsive interweaving chapters, Lunde captures the depth and range of human love in all forms—our capacity to care for species other than our own, our desire to connect with others, and how both these are so often thwarted by the external circumstances of trauma and war. Filled with haunting notions of interspecies kinship, the reverberations of kindness and care, and the innate drive to love and survive despite the odds, this book is one to savor.—Robin Marie MacArthur

IN BRIEF

This Way to the Universe: A Theoretical Physicist’s Journey to the Edge of Reality

by Michael Dine

Dutton, 2022 ($28)

Renowned physicist Michael Dine takes us from the innards of the atom to the depths of black holes in this readable, though occasionally vexing, celebration of science's most mind-bending discipline. The text is conversational and full of delightful asides, but a reader with only one high school physics course under her belt might lose her way in some of the thornier explanations of quantum mechanics, for example. Dine's enthusiastic storytelling makes the read worth it for those who want to finally wrap their mind around string theory or the Higgs boson and are up for an intellectual challenge. —Tess Joosse

Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas

by Jennifer Raff

Twelve, 2022 ($30)

Jennifer Raff, who wrote our May 2021 cover story, “Journey into the Americas,” applies her experience as an anthropologist and geneticist to a sizable task: righting the wrongs of both fields' treatment of Native peoples while addressing how modern methodologies are now closer to understanding the origins of Native Americans. Origin presents how centuries of racist thinking informed theories that were widely accepted. Interstitial case studies could merit entire chapters, from a Monacan burial mound in Thomas Jefferson's backyard to a digression on whether gender or occupation can be inferred from remains. And Raff makes ample space for Native voices through original interviews. —Maddie Bender

Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey

by Florence Williams

W. W. Norton, 2022 ($30)

When journalist and author Florence Williams's 25-year marriage falls apart, her health starts to, too. Desperate to avoid more of the dangerous physical damage that heartbreak can inflict, she pursues information on the “comingled destinies of our cells and our passions.” The result is an engrossing survey of the latest research on the cardiology, neurology and genomics of lost love punctuated by the author's many experiments with healing, from EMDR therapy to a solo canoeing trip to magic mushrooms. Williams's journey through her pain is by turns wrenching, fascinating, funny and, for so many of us, deeply relatable. —Dana Dunham