During a ransomware hack, attackers infiltrate a target’s computer system and encrypt its data. They then demand a payment before they will release the decryption key to free the system. This type of extortion has existed for decades, but in the 2010s it exploded in popularity, with online gangs holding local governments, infrastructure and even hospitals hostage. Ransomware is a collective problem—and solving it will require collaborative action from companies, the U.S. government and international partners.

In 2020 the Federal Bureau of Investigation received more than 2,400 reports of ransomware attacks, which cost victims at least $29 million, not counting lost time and other resources. The numbers underestimate the total impact of ransomware because not all organizations are willing to report it when they fall victim to this crime—and if they do, they do not always share how much they paid. Even these limited statistics, however, demonstrate the increasing boldness of ransomware gangs: the number of attacks in 2020 increased by 20 percent compared with the previous year, and the amount of money paid out more than tripled.

These attacks harm more than the direct targets. Last May, for example, Colonial Pipeline announced that its data had fallen prey to a hacking group. As a result, the private company—which transports about half of the East Coast’s fuel supply—had to shut down 5,500 miles of pipeline. When they heard the news, people panicked and began stocking up on gas, causing shortages. The company paid at least $4.4 million to restore its systems, although the government eventually recovered about half that amount from the attackers, a Russia-based ransomware gang called REvil.

As long as victims keep paying, hackers will keep profiting from this type of attack. But cybersecurity experts are divided on whether the government should prohibit the paying of ransoms. Such a ban would disincentivize hackers, but it would also place some organizations in a moral quandary. For, say, a hospital, unlocking the computer systems as quickly as possible could be a matter of life or death for patients, and the fastest option may be to pay up.

Other solutions are more straightforward and involve pushing organizations to protect themselves better. Cybersecurity defenses, such as multifactor-authentication requirements and better training in how to recognize phishing and other attacks, make it harder for hackers to access systems. Segmenting one’s network means that breaking through to one part of the system does not make all data immediately available. And regular backups allow a company to function even if its original data are encrypted.

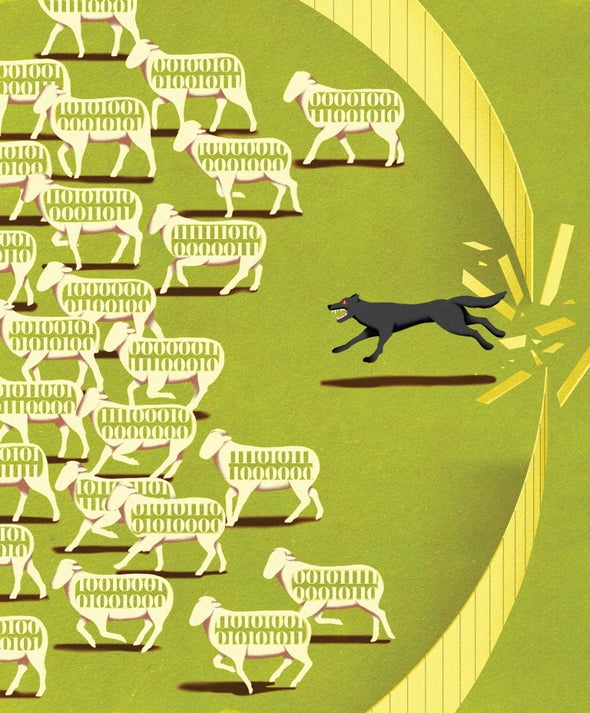

All these measures, however, require resources that not all organizations have access to. Meanwhile ransomware gangs are adopting increasingly sophisticated techniques. Some work for weeks to gain entry to a company’s network and then worm their way through the system, finding the most vital data to hold hostage. Some groups, including REvil, deliberately compromise an organization’s data backups. Others sell instructions and software to help other hackers launch their own attacks. As a result, security personnel must engage in a constant game of cat and mouse.

Collective action can help. If all organizations that fall victim to ransomware report their attacks, they will contribute to a trove of valuable data, which can be used to strike back against attackers. For example, certain ransomware gangs may use the exact same type of encryption in all their attacks. “White hat” hackers can and do study these trends, which allows them to retrieve and publish the decryption keys for specific types of ransomware. Many companies, however, remain reluctant to admit they have experienced a breach, wishing to avoid potential bad press. Overcoming that reluctance may require legislation, such as a bill introduced in the Senate last year that would require companies to report having paid a ransom within 24 hours of the transaction.

Striking back against ransomware will also involve bringing the fight to the criminals—and that requires international cooperation. Last October the FBI worked with foreign partners to force the REvil ransomware gang offline; in November international law-enforcement agencies arrested alleged affiliates of the group. Such collective action among organizations, government and law enforcement will be necessary to curb the boldest ransomware attacks. But it is an ongoing battle—and there is no end in sight.