NONFICTION

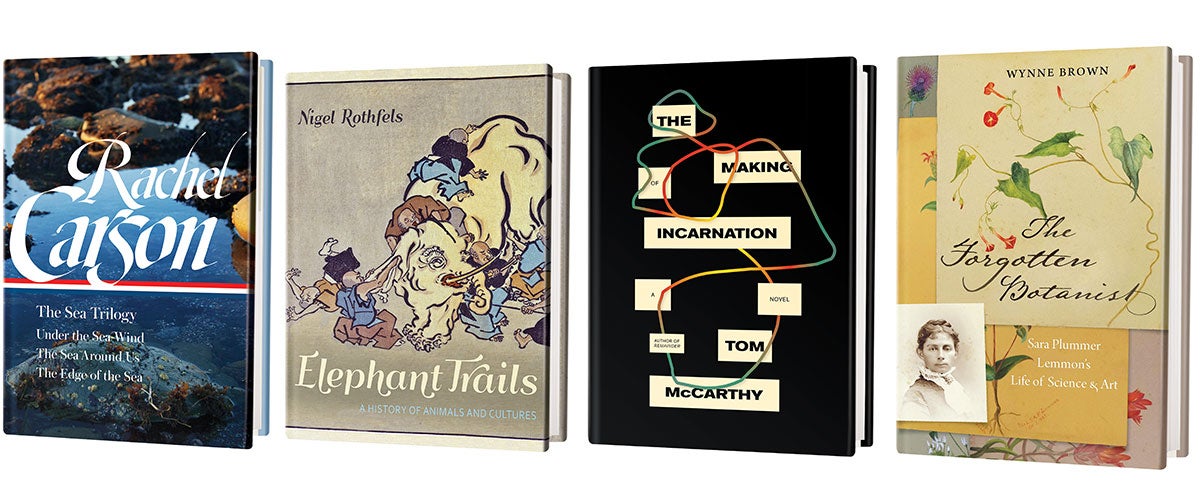

Rachel Carson: The Sea Trilogy

Sandra Steingraber

Library of America, 2021 ($40)

Before Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring in 1962—a literary masterpiece and foundation of the modern environmental movement—she was a marine biologist and a prolific writer on the subject of the ocean. Carson first made her name with a trilogy of best-selling books about the sea, published between 1941 and 1955, books in which she exhibited her distinctive synthesis of complex science and lyrical landscape writing so rich and descriptive that it verges, at times, on the spiritual.

Republished this winter as a single tome by the Library of America, Carson's Sea Trilogy is as gratifying to read today as it ever was; the science, once cutting-edge, may be long surpassed, but much of it will still be new to the lay reader. Each book achieves that rare feat of popular science: crafting a narrative so deceptively simple as to entice readers in and, once there, enchant them enough to stay as much for the prose as for the delicious morsels of data.

Under the Sea-Wind, the first in the sequence, was Carson's first published book. It is unusual and inventive—the flowing, shape-shifting story line taking the form of a succession of episodes seen through the eyes of nonhuman creatures, many of them named: Blackfoot and Silverbar, two sanderlings en route to the Arctic; a mackerel called Scomber; an eel called Anguilla; and so on.

This is a device more often found in children's literature, a signifier of a heavily anthropomorphized animal world, but Carson's intentions were in the opposite direction. Later she explained that she “wanted [her] readers to feel that they were, for a time, actually living the lives of sea creatures.” Giving them names marks these animals as the protagonists of their own stories, subtly shifting the center of gravity away from human concerns and tempting us into investing more fully in the lives of other species. (Readers even take the perspective of the tattered tundra wildflowers at the close of the summer: “No more need of bright petals ... so cast them off ... let the leaves fall, too, and the stalks wither away....”)

The book was well received by critics but did not sell—and a few weeks after publication, Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 ensured that all else was pushed away from public attention. Among many things, it was a difficult time to be making your debut as a writer—something many pandemic-published authors can understand—and Carson faded back into obscurity as her ambitions were overtaken for a decade by her job at the Bureau of Fisheries (later the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) and the needs of her family, where she was the sole earner supporting her aging mother and two motherless nieces.

When finally she published The Sea Around Us in 1951, her persistence was rewarded. It shot into the best-seller charts and stayed there for 86 weeks. This second book took a more conventional form—a sweeping natural history of the ocean—and offered accessible summaries of what was then the forefront of oceanographic science (fathograms, sonic sounding, hydrophonic recordings) while never losing that sense of almost mystical veneration for the interconnectedness of all things. “What happens to a diatom in the upper, sunlit strata of the sea may well determine what happens to a cod lying on a ledge of some rocky canyon a hundred fathoms below, or to a bed of multicolored, gorgeously plumed seaworms carpeting an underlying shoal, or to a prawn creeping over the soft oozes of the sea floor in the blackness of mile-deep water.”

This sentence is typical of Carson's style: at once exact and expressive, with that same sense of zoomed-out, joined-up thinking that would later enable her to connect the disparate dots of the research into DDT as it existed in piecemeal form in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Sea Around Us was met with a rapturous reception and propelled Carson to literary celebrity. It is not hard to see why: the book is packed with captivating detail, and on almost every page one finds a passage of uncommon beauty. The dated science does not detract from one's enjoyment; if anything, it adds to it because it allows the reader to look afresh at the ocean and see it once more from a place of greater ignorance. Oh God, as the Breton prayer goes: Thy sea is so great, and my boat is so small.

The ocean summoned up in The Sea Around Us is an alien world, where “strange and fantastic” creatures lurk in its darkest recesses, their “eyes atrophied or abnormally large, their bodies studded with phosphorescent organs.” It is a place where mists of plankton swirl through shafts of sea-green light, where flying squid hurl themselves onto the decks of passing vessels. To read it is to confront how we have coexisted alongside a vast realm almost unknown beyond our own small circle of light.

Carson tells us of the amazement felt by the crew of the Bulldog in 1860, when a sounding line was brought up from a depth of 1260 fathoms—a depth then suspected to be entirely devoid of life—with 13 starfish clinging to it. It was as if a space shuttle were now to return to Earth with unexpected stowaways onboard: “The deep has sent forth the long coveted message,” as the ship's naturalist recorded it at the time. There was a whole other world down there.

We learn of the discovery in 1946 of the detection by echo sounding of a “phantom bottom” of “wholly unknown nature,” which appeared to hang suspended between the surface of the ocean and the sea bed, at a depth of around 1,500 feet. First mistaken for a chain of sunken islands, it was later detected to stretch across much of the ocean and was observed to move—rising to near the surface at night and sinking into the depths during the day, “apparently strongly repelled by sunlight.” This phenomenon we now call the deep scattering layer is made up of millions of small fish, but when viewed from 1951 its first detection retains enough proximity and mystery to send a shiver up one's spine. What Carson's descriptions most bring to mind is the sentient ocean of Stanisław Lem's 1961 sci-fi classic Solaris—and that same sense of being in the presence of an unknown, unnerving being with its own, incomprehensible agenda.

Of the trilogy, The Sea Around Us is by far the most vivid and intoxicating. Partly this is a function of the strangeness of its subject matter, the expanse of the great black deep. The relatively prosaic setting of the third book, The Edge of the Sea—the seashore, where so many of us have trundled with our little nets—perhaps inevitably pales in comparison. Still, Carson is our constant, erudite companion, who chatters companionably of the most interesting crabs and seaweeds, crustaceans and barnacles she knows, all prettily accompanied in this edition by the original illustrations by Carson's friend and colleague Robert W. Hines.

Truly, this third book is more of a field guide and was always intended as such, but it nonetheless was produced with Carson's trademark flair: snail shells are “coiled like a French horn”; comb jellies move with “elusive moonbeam flashes.” She recalls one rock pool “only a few inches deep, yet it holds all the depth of the sky within it, capturing and confining the reflected blue of far distances.”

Carson once declared that if there was poetry in her books about the sea, it was not because she put it there “but because no one could truthfully write about the sea and leave out the poetry.” Perhaps. But one cannot help but think of Carson working late into the night, crafting her perfect sentences with the precision of a jeweler. She was a scientist, yes, but also a disciple of the sea. These books are devotional works.

The sea, through Rachel Carson's eyes, is a wild and majestic place. At its edges, contemplating the waves, she writes, “We have an uneasy sense of the communication of some universal truth that lies just beyond our grasp.” Though I live on an island, this had not previously occurred to me. Now, having read Carson's Sea Trilogy, I look out my window and see the water as if for the first time.—Cal Flyn

IN BRIEF

Elephant Trails: A History of Animals and Cultures

by Nigel Rothfels

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021 ($40)

Historian Nigel Rothfels traces the human relationship with elephants from prehistoric days to the present, writing with compassion for the mighty mammals and condemnation for our abhorrent treatment of them. He captures the ache and cruelty of colonization and enslavement; it is, at times, a gruesome read but a sobering one. This book will appeal to those fascinated by the mythology and legacy of elephants, as well as animal lovers who fight for the liberation of all living creatures. —Jen Cox

The Making of Incarnation: A Novel

by Tom McCarthy

Knopf, 2021 ($28)

Tom McCarthy's inventive latest novel follows Mark Phocan, an employee of a motion-capture firm assisting with the special effects of sci-fi thriller Incarnation. As Phocan deploys the company's technology across contexts from war to sex, he becomes entangled in a mystery involving a fictionalized version of industrial psychologist and engineer Lillian Gilbreth, whose time-and-motion studies may have uncovered something far more valuable than saved labor. Though intensely technical, these nested narratives are steeped in mysticism, linking time, light and energy to the nature of being. —Dana Dunham

The Forgotten Botanist: Sara Plummer Lemmon’s Life of Science and Art

by Wynne Brown

University of Nebraska Press, 2021 ($27.95)

Sarah Plummer Lemmon was a 19th-century frontierswoman. She nursed wounded Civil War soldiers, established the first library in Santa Barbara, lobbied for the golden poppy as California's state flower and became a prolific botanical illustrator. She also collected and described numerous plant specimens across the American West, but for years her scientific discoveries were credited only to “J. G. Lemmon & wife.” In this attentive and richly researched portrait, writer Wynne Brown honors not just Plummer Lemmon's many accomplishments but her verve and courage. —Tess Joosse