As social beings, when thinking about autism we tend to focus on its social challenges, such as difficulty communicating, making friends and showing empathy. I am a geneticist and the mother of a teenage boy with autism. I too worry most about whether he’ll have the conversational skills to do basic things like grocery shopping or whether he will ever have a real friend. But I assure you that the nonsocial features of autism are also front and center in our lives: intense insistence on sameness, atypical responses to sensory stimuli and a remarkable ability to detect small details. Many attempts have been made to explain all the symptoms of autism holistically, but no one theory has yet explained all the condition’s puzzling and diverse features.

Now, a growing number of neurocognitive scientists think that many traits found in people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may be explained centrally by impairments in predictive skills—and have begun testing this hypothesis.

Generally, the human brain determines what’s coming next based on the status quo, plus what we recall from previous experiences. Scientists theorize that people with ASD have differences that disturb their ability to predict. It’s not that people with autism can’t make predictions; it’s that their predictions are flawed because they perceive the world “too accurately.” Their predictions are less influenced by prior experiences and more influenced by what they are experiencing in the moment. They overemphasize the “now.”

When the connections between an event and a consequence are very clear, people with ASD can learn them. But the real world is an ever-changing environment with a lot of complexity and sometimes contingencies and deviations are as not as obvious. Many individuals with autism have difficulty figuring out which cues are most important, because there are too many other cues complicating the environment and competing for attention.

Five years ago, the Simons Foundation’s autism research initiative launched SPARK (Simons Powering Autism Research for Knowledge) to harness the power of big data by engaging hundreds of thousands of individuals with autism and their family members to participate in research. The more people who participate, the deeper and richer these data sets become, catalyzing research that is expanding our knowledge of both biology and behavior to develop more precise approaches to medical and behavioral issues. Scientists are now recruiting SPARK participants to study directly observable aspects of prediction more closely. There are two components that can be observed: the ability to learn the connection between an “antecedent” event and its consequence, and responses to predictable events.

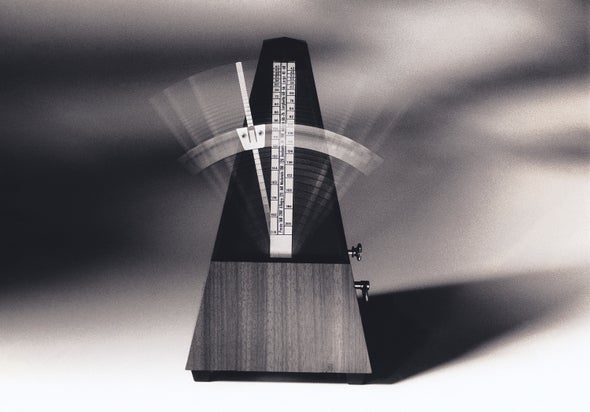

Pawan Sinha of MIT recently published results from a study showing that people with ASD had very different responses to a highly regular sequence of tones played on a metronome than those without ASD. While people without ASD “habituate” to the sequence of regular tones; people with ASD do not acclimate to the sounds over time. Rather, their responses after several minutes of hearing the tone sequence were still as robust as they were when they were first played. Using SPARK’s powerful digital platform, Sinha and colleagues are now able to conduct similar experiments online with a much larger number of people with autism.

As the researchers acknowledge, the connections between the decreased habituation and real-world challenges in people with autism are still not clear, but testing multiple aspects of prediction in more naturalistic contexts in a larger number of people will help address that knowledge gap. Eventually, a better understanding of the cognitive processes in autism may help to improve interventions—for example, by tailoring different prediction-based interventions to individuals with varying prediction styles.

Every parent of a teenager has their share of challenges, and, for me, an ongoing issue for my son is that he really seems to enjoy engaging in behaviors that will elicit a response from someone. Some of these “habits” have small consequences. For example, he loves to empty entire bottles of soap, detergent, and cooking oil. He also likes to throw things out of his window. More than once, I’ve been out walking the dog and noticed pants on the roof of our house.

While one cannot deny the satisfaction inherent in dumping a lot of fine olive oil into a drain, it’s impossible for me to ever fully understand why my son does any of these things. Still, I have a strong suspicion it’s because he knows these behaviors will elicit a predictable response from me. I have learned that the more I respond, the more he will be encouraged to behave this way. So, now, when I find an empty bottle of detergent in the laundry room—or an entire roll of toilet paper in the bowl—I don’t make a big deal of it.

Then comes the test of tests: one of his most problematic behaviors is touching our dog’s rear end. He knows he is not supposed to do this. He knows that, likely, someone might gasp aloud and then tell him to wash his hands. If his abilities to predict are impaired, then it makes sense that doing things that elicit predictable responses must be satisfying. Having a scientific framework that helps explain his behaviors helps me cope with them. More importantly, a better understanding increases my empathy for him, helps me explain his actions more clearly to others, and helps me remember not to react strongly.

Scientists are also using SPARK to test other aspects of prediction in autism, including language. Harvard University scientist Jesse Snedeker is recruiting participants from SPARK to test whether children with autism are less likely to make accurate predictions during natural language comprehension of simple sentences. These experiments will explore if children with autism differ in using linguistic context to predict upcoming words when hearing a story or conversation. The results will help scientists learn whether impairments in prediction in different people with autism are more broad or more specific to different domains.

As a parent and a researcher, my greatest hope is to help moms like me, children like Dylan, and families like mine. The challenges of understanding autism are many, but a better understanding of predictive patterns in autism will help us all—researchers and families—understand the many “whys” that remain a hallmark of autism.

This is an opinion and analysis article; the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.