Although it is the sharp edge of the battle to end hunger, you could be forgiven for thinking you were watching a reality TV cooking show. Under the low peak of Bwabwa Mountain in Malawi, in a village on a tributary of the Rukuru River, about 100 people gather around pots and stoves. Children crowd around a large mortar, snickering at their fathers’, uncles’ and neighbors’ ham-fisted attempts to pound soybeans into soy milk. At another station, a village elder is being schooled by a man half his age in the virtues of sweet potato doughnuts. At yet another, a woman teaches a neighbor how he might turn sorghum into a nutritious porridge. Supervising it all, with the skill of a chef, the energy of a children’s entertainer and the resolve of a sergeant, is community organizer Anita Chitaya. After helping one group with a millet sponge loaf, she moves to share a tip about how mashed soy and red beans can be turned into patties by the eager young hands of children who would typically never volunteer to eat beans.

There is an air of playful competition. Indeed, it is a competition. At the end of the afternoon the food is shared, and there are prizes for both the best-tasting food (the doughnuts win hands down) and the food most likely to be added to folks’ everyday diets (the porridge triumphs because although everyone likes deep-fried food, doughnuts are a pain to cook, and the oil is very expensive).

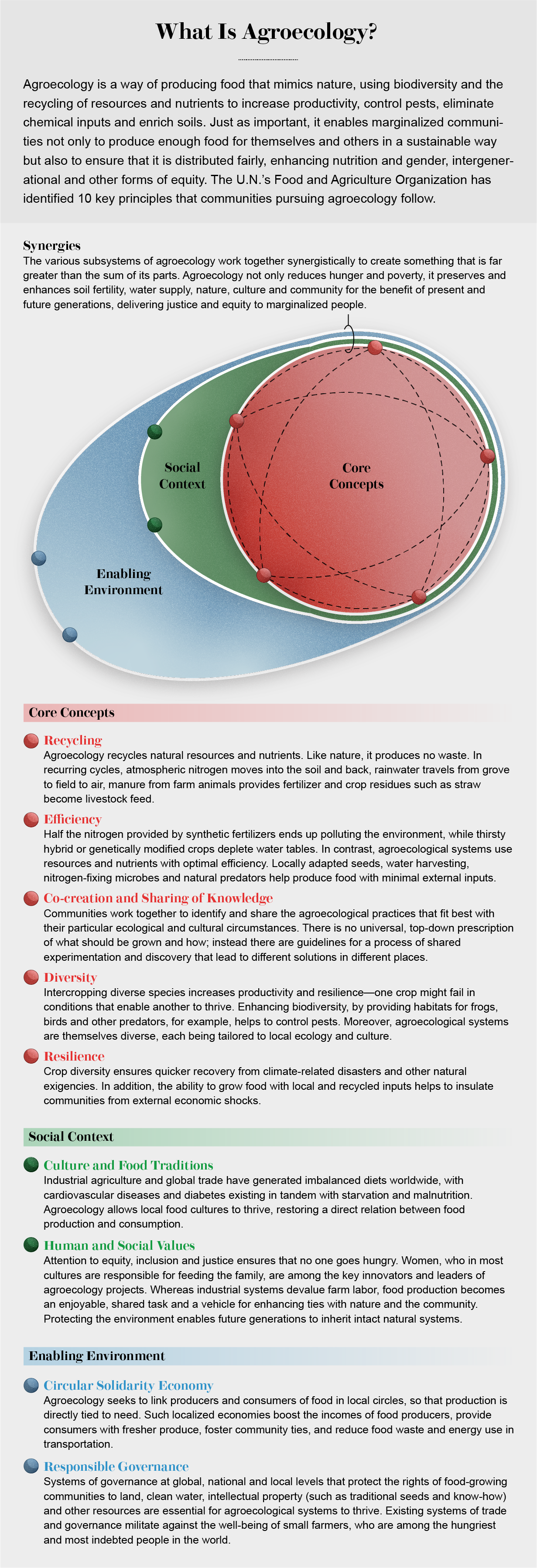

This is a Recipe Day in Bwabwa, a village of around 800 people in northern Malawi. These festivals are sociological experiments to reduce domestic inequality and are part of a multifaceted approach to ending hunger called agroecology. Academics describe it as a science, a practice and a social movement. Agroecology applies ecology and social science to the creation and management of sustainable food systems and involves 10 or more interconnected principles, ranging from the maintenance of soil health and biodiversity to the increase of gender and intergenerational equity. More than eight million farmer groups around the world are experimenting with it and finding that compared with conventional agriculture, agroecology is able to sequester more carbon in the soil, use water more frugally, reduce dependence on external inputs by recycling nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, and promote, rather than ravage, biodiversity in the soil and on farms. And on every continent, research shows that farmers who adopt agroecology have greater food security, higher incomes, better health and lower levels of indebtedness.

Chitaya told me that at the turn of the millennium, when Bwabwa’s farmers were still practicing conventional agriculture, “there were times when we wouldn’t be able to eat for days. My first child was malnourished.” Now her oldest son, France, is a very healthy adolescent, helping teach other boys how to cook. The pediatric malnutrition clinic near Bwabwa has closed down for want of cases—though in Malawi as a whole, more than a third of the children younger than five years are stunted by malnutrition. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, whose devastating economic effects have deepened malnutrition across the world, agroecology continues to help Bwabwa evade hunger.

Yet when policy makers attend a United Nations Food Systems Summit in the fall of 2021, the solutions on the table for world hunger will exclude agroecology. The summit’s sponsors include the Gates Foundation, whose preferred solution is a set of technologies modeled on the Green Revolution. Despite a great deal of evidence that the Gates’ Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa has failed, one of its leading acolytes from Rwanda will chair the U.N. Summit. Advocates for agroecology, such as the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa, which represents 200 million food producers and consumers, have too few resources to impact a process that increasingly silences their voices.

Ending hunger requires much more than pulling more food from the ground; it involves grappling with entrenched hierarchies of power. Over the past decade food production has generally outstripped demand—there is more food per person than there ever was. But because of global and regional inequalities, exacerbated by the recent pandemic, levels of hunger are higher now than in 2010. In other words, more food has accompanied more hunger. People are deprived of food not because it is scarce but because they lack the power to access it.

The global food system was originally established under colonialism, when the agriculture and land-ownership patterns of much of the tropical world were reconfigured, and tens of millions of enslaved and bonded laborers were shipped around the world to provide Europeans with cane sugar and other tropical crops for which they had developed a taste. Far from ending with colonialism, however, this system of food extraction has grown only stronger because of conditions attached to loans from international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). To pay its debts, Africa now exports everything from roses to broth.

Agroecology frees the world’s poorest farmers from such structures of control and shifts the balance of power in the global food system to people like Chitaya, one of billions who reside at the very bottom of the socioeconomic pyramid. Little wonder, then, that it is unpopular with conventional agricultural businesses, governments in the Global North and the organizers of the food systems summit. Its recognition that systemic problems require systemic solutions makes agroecology a threat.

Hunger in Malawi

Over a lifetime of trying to get to the bottom of why there is hunger and what might be done about it, I have traveled from within organizations like the U.N. and the World Bank to protest lines outside and within the World Trade Organization. During the past decade, however, I have also had a scientific education at the hands of some of the world’s poorest farmers.

My first visit to Bwabwa was in 2011, at the invitation of my graduate school friend Rachel Bezner Kerr. Now a professor of development studies at Cornell University, Bezner Kerr had arrived in Malawi a decade earlier to find herself in the middle of an economic crisis. Malawi had suddenly reduced fertilizer subsidies—and that, too, while the HIV/AIDS pandemic was wreaking humanitarian and economic havoc. Farmers, most of whom practiced industrial agriculture, which requires expensive chemical inputs, were desperate. Bezner Kerr wanted to be of service as she developed a project for a master’s degree, so she sought the most disadvantaged families to support in her research. She was lucky to meet Esther Lupafya, a nurse who headed the maternal and child health program at a clinic in the small town of Ekwendeni. Together they identified farmers, including Chitaya, who were ready to try a different kind of agriculture—one that would free them from dependence on global agrobusiness and its allies.

Getting to Bwabwa involves a six-hour drive north from Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe. Lined with signs heralding the projects of several nongovernmental organizations and foreign aid institutions, the northern road from the Lilongwe airport tracks the eastern shore of Lake Malawi, the continent’s third-largest freshwater lake. After passing northern Malawi’s biggest city, Mzuzu, with its six-story Bank of Malawi Building, and the smaller town of Ekwendeni, you follow dirt roads to reach Bwabwa. Whereas the large, flat, irrigated fields off the main highway are neat monocultures of corn, the fields near the village are drier, smaller, canted at every angle and packed with twirling thickets of different crops, each tailored to the needs of the family tending it and the capacity of that particular field’s ecology.

Northern Malawi did not always look like this. The first white man to visit was Scottish Presbyterian David Livingstone in 1858. His missionary campaign led to the establishment of the British Central African Protectorate, which later became Nyasaland. Photographs from the time show scrubland. British agriculturist B. E. Lilley gazed on Malawi in the 1920s and declared: “The time has not arrived when the native can be looked to as a person who can be relied upon to raise produce to anything [like] the extent that the white man raises it.” Similar attitudes persist to this day, though they are now couched in contemporary language.

Keen to wring what they could from the colony’s resources, the British began to export ivory and forest products, moving on to the crops that would transform Malawi’s land and economy: tea, cotton, sugar and tobacco. The colonists took over the land, but they needed workers, so they imposed a hut tax, an annual household fee payable in cash. Initially families paid the colonists by selling their stores of wealth, usually livestock, until there was nothing left to liquidate. Then they sent able-bodied men to sell their labor, in Malawian plantations and the mines farther south. Debt turned self-sufficient farmers and pastoralists into manual workers, laboring for a pittance.

Debt also turned Malawi into a pawn of its creditors. Malawi became independent in 1964, only to spend the next 30 years under autocrat Hastings Banda. Western donors rewarded his iron-fisted regime with high-dollar loans to support the country’s industrial development while ignoring its worsening malnutrition. Such loans became the instruments of Malawi’s, and in fact Africa’s, hunger. In the early postcolonial period, Africa was a net food exporter, selling 1.3 million tons a year from 1966 to 1970. But the oil-price crisis of the 1970s forced African governments to borrow even more from the World Bank and the IMF. These so-called structural adjustment loans came with strict conditions that, among other measures, slashed public spending on education and health care and privatized national assets. Further, African countries were instructed to concentrate on exports of the colonial-era crops, which would earn the dollars with which they might repay their debts.

Despite paying an average of $100 million per year to its creditors throughout the 1980s, however, Malawi remains one of the most indebted countries on Earth. Worse, devoting the richest land to growing cash crops for export, instead of food crops for subsistence, meant that structural adjustments had by the 1990s turned Africa into an importer of a quarter of its food. Between 2016 and 2018 Africa imported 85 percent of its food from outside the continent—a debilitating dependence.

Trial, Review, Exchange

In 1992 a national survey revealed that 55 percent of Malawian children had failed to reach the appropriate height for their age—a key measure of malnutrition. The government tried to defy the austerity imposed by international banks and donors by subsidizing fertilizers for farmers but eventually caved to their demands to instead prioritize paying off the loans. Lupafya and Bezner Kerr began their work soon after these supports were removed, establishing the Soils, Food and Healthy Communities (SFHC) initiative in Ekwendeni in 2000. Starting with 30 farmers, the SFHC now works with more than 6,000 people across 200 villages to promote agroecology.

Along with Chitaya and others, the women began with a round of experiments, intercropping local groundnuts and other legumes. This double-legume system allowed the farmers to harvest nuts and beans for their children and then dig the nitrogen-rich residue back into the soil to boost maize production—without buying fertilizer. Some farmers went further, experimenting with vegetable intercropping patterns. Simultaneously, the SFHC developed a system of peer review, in which the participants met regularly to discuss measures to improve soil fertility. Women farmers had long been exchanging seeds and knowledge to grow finger millet, a drought-tolerant plant that produces highly nutritious grains that make for hearty porridge and, if you can stomach it, sour beer. The SFHC formalized this tradition of evaluating and sharing information.

By running trials of different legume cropping systems in a “mother” location in the middle of different villages, farmers could then adopt “baby” trials in their own fields based on their preferences for soil health, nutrition and the time they could spare to tend the crops. Through discussions and iterations over the years, initial trials grew from a few dozen households to reach thousands of farmers, with a pigeon-pea-and-groundnut combination proving to be the most successful in fixing nitrogen. As the soil improved, some farmers, many of them women, did well enough not only to feed their families but also to sell a respectable surplus at the local market.

Still, every farmer, every field and every season are different, so the experiments continued. Some women tried seemingly incongruous combinations such as soy and tomatoes—originating in Asia and the Americas, respectively—alongside indigenous African varieties such as finger millet. (Millet cultivation had earlier been discouraged because the grain could not be exported for dollars, but it persisted because women often brew it into beer as a means of earning extra income.) In Bwabwa, the fields are a mixture of foreign and native varieties, selected through trial and observation, with networks of farmers exchanging knowledge and ideas and reviewing one another’s work.

That openness to experimentation and adaptation explains why, around March, it is possible to see in the unpromising red soil a cultivation system that looks like it may not belong. Tall rows of corn burst from the ground. Twirling around them are pole beans, and at their feet are the fat, dark fan-shaped leaves of local pumpkin, together with their blossoms. In Mesoamerican agriculture, this kind of technique is known as the three sisters: corn, beans and squash.

In Malawi, locally adapted varieties work together in similar ways: the corn or millet provides the starchy cereal that forms the backbone of every meal. The stalks also scaffold the beans, which yield protein and fix nitrogen. Root nodules in legumes (such as beans and groundnuts) are a site of symbiosis between the plant and rhizobia bacteria. The plant provides the bacteria with energy; the bacteria take nonreactive nitrogen molecules from the air and turn them into ammonia and amino acids for the host. This works well for cereals, which need bioavailable nitrogen to do well. The pumpkin (or other squash) provides big leaves for shading out weeds, and its flowers attract beneficial insects that keep pest pressure down. Plus, at the end of the season, there are gourds.

When put together, these crops produce more food per unit area than when they grow alone. Polycultures are demonstrably more abundant than monocultures. After harvest, the crop residue is reincorporated into the soil to build fertility and structure for the soil’s biome.

In the early 2000s, as soil fertility in Bwabwa improved, some of the poorest women began to harvest an abundance of cereal, beans and vegetables. Interest in the cropping techniques spread. But despite real improvements in food production, child malnutrition remained puzzlingly high. Some of the farmers in the project, excited that they were becoming agronomists, started to wonder how to tackle the problem more directly. As they would discover, they had made progress in freeing themselves from external structures of power—but had yet to tackle internal ones.

Wrestling Down Patriarchy

Through her work at the pediatric clinic, Lupafya had formed a suspicion: tradition was partly to blame for infant malnutrition. Ethnographic research across the SFHC villages confirmed her hunch. Within the patriarchal extended family, mothers-in-law have authority over their daughters-in-law. When an ill-founded parenting tip—that children cry because they are not being given solid food—is propagated through these networks, young mothers often find themselves counseled to wean their children at the age of two months. This advice runs counter to overwhelming scientific evidence that exclusive breastfeeding for six months and then a mix of breast and solid food until two years of age offer children the best start in life.

Lupafya crafted a way to walk the tightrope of respectful disagreement. The SFHC trained village women and men as facilitators to broker difficult conversations, particularly those between mothers- and daughters-in-law. Through monthly meetings and leadership from Lupafya and others, the science spread, and the misinformation was dispelled.

Lupafya learned something as well. “Change begins with denial,” she told me. “It is the one who debates the most who will change.” Having tackled the availability of food and breastfeeding practices, the grassroots social scientists moved to another determinant of infant malnutrition they had identified: domestic violence and, more broadly, patriarchy. Women’s autonomy is linked with improved child nutrition indicators. As they observed, gender inequality meant that mothers had to spend time cooking, cleaning, managing the farm and breastfeeding. To have men help in domestic labor would increase women’s autonomy. The question was: How do you get men to cook?

To find out how this transformative change happened, I worked with the SFHC team for more than a decade, documenting Chitaya’s work in a film called The Ants & the Grasshopper. Chitaya had first met Lupafya when she visited the pediatric nutrition clinic. The older woman, Mama Lupafya as she is called, had supported her in a difficult marriage, one into which Chitaya had been coerced. Through attending workshops hosted by the SFHC, then by finding work as one of its trainers, and through long and difficult work in her home, Chitaya has transformed her marriage into one characterized by equality.

There are times when her husband, Christopher Nyoni, struggles to pull his weight in the house. He is afflicted by night blindness, a possible consequence of his own malnutrition early in life. When it gets dark, he is no longer able to cook or clean and needs help finding his way around the house. But by the light of day, he can be seen hunched over a stove or doing laundry or fetching water—all of which are traditionally women’s work. It is a sign of Chitaya’s success that Nyoni is keen to break with patriarchal tradition: “I do not want my son to get married the way I did,” he told me.

The pathway to transforming this and other gender relationships in Bwabwa lay through changing the culture around food. An initial effort to achieve this shift involved door-to-door organizing. Members of the SFHC would visit households with an expert and offer to teach men how to cook novel foods, such as soy. After an enthusiastic afternoon gathered around a stove, surrounded by exhortations to do better, the men promised they would change. They did not. So the SFHC farmers brainstormed an alternative.

A constant worry for men was the social stigma of doing the effeminate work of cooking. “What if my friends see me?” asked Winston Zgambo. Having tried to cater to men’s embarrassment by offering private cooking lessons, the SFHC team tried the opposite. They held public cooking competitions for whole families. On Recipe Days, all men were involved in cooking—and it was fun. By gamifying the change in behavior through offering prizes and social recognition for success, the women cracked open the possibilities for changing not just food culture, but inequalities in power within the home.

Data from the SFHC’s work speak for themselves. Participation in the program moved children from being below the average weight for their age to surpassing the average. A recent study in which women farmers showed other mothers how to farm led to a range of benefits, from increased dietary diversity for children to lower maternal depression rates and higher rates of fathers’ participation in chores.

A Teeming Future

Agroecology means taking care not just of all humans but also of the ecosystems on which we depend. Under chemical agriculture, farmers grow a single crop. They buy fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and access to water, and if necessary, they rent pollinators to maximize the yield. They use the revenue from selling the harvest to pay their bills and debts. In agroecology, farmers find ways not to exterminate pests but to reach an ecological equilibrium. They accept a little crop loss while providing habitats for predators and introducing other forms of biological control to obtain a much more robust and resilient ecosystem. In northern Malawi, biodiversity is part of the SFHC’s success, as it is in every successful agroecological system. There are more insects, amphibians, reptiles, fish, birds and mammals in these landscapes than in the barren green deserts of modern monoculture.

In a world of extreme weather, agroecological diversity—both social and biological—is a source of resilience. When Hurricane Ike ploughed through Cuba in September 2008, it left trees and debris littering the fields. In Sancti Spíritus province, researchers noticed that the farms that followed the principles of conventional agriculture, with vast expanses of the same kind of crop, took around six months to recover from the devastation. But the most diversified farms, with tall plantains, fruit trees, perennial crops and ground cover, were able to recover 80 percent of their prestorm capacity in just two months. With high canopy trees blown over, more light fell on other plants in the understory, which grew faster: the diversity constituted a kind of botanical insurance portfolio. Moreover, families living on diversified farms could save some trees the morning after the storm, when conventional farm workers were far from the fields where their labor was seasonally contracted.

Agroecology also enables income resilience. Small farmers typically receive very little support. Instead they need to manage the flows of cash around the farm themselves. Conventional agriculture has one big burst of cash at harvest time, which may or may not be enough to pay off farming-related debts and dwindles throughout the year. With agroecology, on the other hand, income streams can be augmented by means of crops that mature in the leanest times. In Mexico, for instance, one group of farmers supplements its corn income with countercyclical honey and coffee harvests.

In the absence of reliable banks, farmers have sometimes turned to creating their own circular economies and exchanges. Many places have local grain stores that help to manage the booms and busts in harvests and hunger. In Bwabwa a few years ago women set up a credit circle to help manage cash flow and to develop other income streams, such as the sale of “climate change stoves,” cooking stands that require much less wood than conventional wood-burning methods. A dozen women pooled their resources and took turns borrowing the cash and then repaying it. But the savings circle was wiped out in the IMF-mandated devaluation of the Malawian kwacha (currency) in 2012.

The COVID-19 crisis has made farmers’ lives harder. Rising food prices have strained finances, and with resources diverted to emergency mitigation measures so that communities could stay home and stay safe, everyone’s life has become harder. Yet agroecological practices appear to have enabled the SFHC’s villages to endure the pandemic better than communities outside the project.

Feed the World

What happens in Malawi and among the hundreds of millions of farmers experimenting with new kinds of agroecology matters for the planet. Agroecology offers the ability to do what governments, corporations and aid agencies have failed to do: end hunger. For a while, it might have been easy to respond to agroecology by saying “that’s all very nice, but it won’t feed the world.” But farming families that engage in agroecology have improved indicators of income and nutrition. From Nepal to the Netherlands, when agroecology is not confined to the field but extends into the home with equality and into community networks of exchange and care, farmers are financially and physically better off.

With ideas from the World Economic Forum and with support from the food and chemicals industry, the solutions on the table at the U.N. meeting are far less imaginative. Nor do they go far enough to remedy or even acknowledge the environmental and other harms committed by industrial agriculture. This supposedly scientific method of growing food is one of the largest drivers of climate change. Algae blooms from nitrogen and phosphate pollution are devastating aquatic life. Pristine forests are falling to ranches and plantations. Aquifers are being drained for thirsty cash crops. Fertile soil is turning to sterile dust as synthetic chemicals kill essential microbes, and pesticides are decimating insects on which extended chains of life depend.

This past July the Rockefeller Foundation reported that whereas Americans spent $1.1 trillion on food in 2019, the additional external health, environmental, climate change, biodiversity and economic costs associated with the food industry were $2.1 trillion. That is quite a debt—and one that the industry will never have to pay. The rest of the world shoulders the cost. Yet the firms behind this damage are the ones offering solutions at the summit.

We know how to do better. Agroecology more than fits the bill—not only because the crops grown are more diverse but because the social arrangements that surround them are more cognizant of power. Industrial agriculture’s hidden costs are precisely the ones agroecology makes explicit. Its pathways reward the acumen of those on the front lines, support the livelihoods of the poor and protect the biodiversity of the planet. Its researchers and practitioners are already hard at work, teaching and learning from one another.

Such networks of knowledge undo the colonial savior complexes to which many development experts are still tied. Instead, under agroecology, as Chitaya puts it, “women can teach men, Black people can teach white people, the poor can teach the rich.” She reflects on the certainties of struggle ahead, particularly as the powerful seem to be doubling down on industrial agriculture. “So much has been lost. But it’s never too late to change.”

Editor’s Note (10/18/21): This article has been edited after posting to correct the name of the Malawian town of Ekwendeni.