NONFICTION

The Last Winter: The Scientists, Adventurers, Journeymen, and Mavericks Trying to Save the World

Porter Fox

Little, Brown, 2021 ($28)

With each new report about the impending—and ongoing—effects of climate change, it’s easy to catastrophize. In the coming decades, as glaciers around the planet melt and sea levels rise, hundreds of millions of people living in low-lying coastal communities will be forced to relocate to higher ground. But the mountains are no safe space either, as wildfires increase and water becomes scarce—both of which are a result of disappearing snowfall. “Frozen water has made our world,” writes author Porter Fox. “And as it vanishes, everything in our backyards, our cities, our homes, our jobs, and our lives is going to change.”

For the 670 million people living in high mountain regions worldwide, the shrinking glaciers (as well as the rivers they feed) will leave those once snowy areas without water, parched to the point of geologic dehydration. Within the next three decades the length of winter in the U.S. could decline by 50 percent. A 2004 study in Climatic Change predicted a drop in snowpack depth of 25 to 100 percent by the end of this century; another study warns that the Southwest will not have enough snow to support ski operations by 2050. Such dramatic losses will devastate the West’s forests and dry up rivers like the mighty Colorado, which supplies water to some 40 million people and has been in drought for more than 20 years. Indeed, the first-ever water-usage cutbacks were applied to its basin states in August.

But what’s lost in those reports and the doomsaying that often follows is the creative, persistent people behind the study abstracts: those dedicating their lives (and sometimes risking them in the process) to research in some of the world’s most remote and wild places. In The Last Winter, Fox puts names and backstories to much of the data as he travels from Washington State to Alaska to Greenland to Switzerland and beyond, connecting with the scientists who are often painstakingly collecting information that the rest of us rely on to make sense of our changing planet.

The book is part adventure travelogue, part profile collection and part essay, as Fox, a lifetime skier, contemplates what the world will be like without snow. Because of this mash-up, The Last Winter can feel a bit disjointed at times, and it’s occasionally hard to keep tabs on who’s who, as Fox leaps from one person to another and from location to location. (It doesn’t help that the pandemic interrupted the book’s far-flung reporting.) But when he settles into a new character and destination, Fox does an excellent job of humanizing the scientists. In Washington, he goes on a backcountry ski tour with Kelly Gleason, a researcher at Portland State University who helped pioneer the study of a particular feedback loop: when black carbon from burned trees falls onto snow, it absorbs more sunlight, causing the snow to melt faster and dry out the forest earlier, creating more fire-prone forest. The idea had come to her while skiing in a burn scar. When Fox asks Gleason what will life be without winter, she responds: “Yeah, I’m not ready to deal with that.”

The writing is at its best when Fox describes the landscapes. In the Arctic, for example, “It never really gets dark.... The reflective surface of the snow and glaciers glows blue under the moon and stars. Night is an afterworld of ghostly shapes and distant sounds, like opening your eyes underwater.” He meditates on what the fading of winter will mean for the cultures that rely on it—both the ancient native cultures and modern recreational ones like skiing. In Greenland, Fox embeds with a crew of Inuit guides who seem more prepared to confront the harsh realities of climate change than most.

Still, it’s the research on the ongoing losses in the cryosphere that provide the book’s heft, if only because of the dire state it portrays. As Fox notes when discussing the multiplying effects of droughts, forest fires, diminished snowpack and longer summers: “As with most in the world of climate change, the problem compounds. Lack of snow cover allows sunlight to sustain new plant life earlier in the spring—adding more demand on the shrinking water supply and more fuel for fires.”

If there are faults to The Last Winter, it’s that the book suffers from the same shortcomings as much reporting on climate change: it’s too focused on the canaries in the coal mine. The rapid pace at which we’ve already lost glaciers and biodiversity (to name just two examples) haven’t yet propelled our species to take up aggressive action. Fox writes with sincerity that “measurement is the key to solving climate change,” but it’s a wide-eyed view. It’s what we do collectively with those data that matters most now, and the book offers few nods toward the type of transformative solutions we need.

Coming away from reading The Last Winter, there’s no other way to feel but, well, full of dread. As Fox notes, “The sedating effects of modern convenience [make] it seem like everything [is] going to be alright, like someone would figure everything out.”—Ryan Krogh

ESSAYS

Facts and Fables

Aesop’s Animals: The Science behind the Fables

by Jo Wimpenny

Bloomsbury Sigma, 2021 ($28)

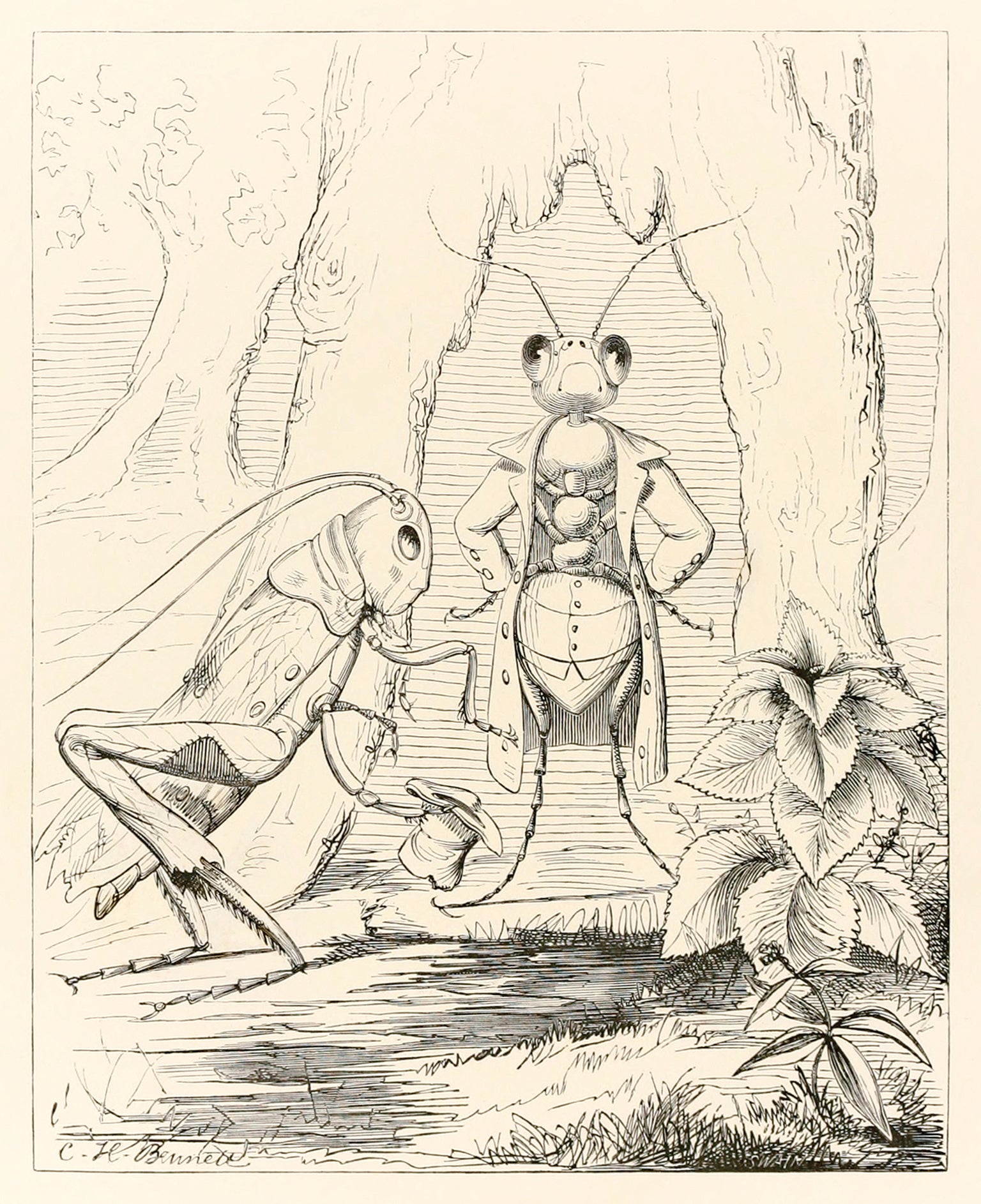

Come for the fables and stay for the behavioral research in this jam-packed but delightful collection of essays. Each chapter of Aesop’s Animals begins with a tale from the mononymous Greek storyteller—“The Ant and the Grasshopper” (right), “The Fox and the Crow,” plus seven others—and then weighs its plot against centuries of inquiry. Do lions reward acts of altruism, like Aesop’s big cat with a thorn in its paw? Are wild wolves capable of deception—sheep’s clothing or otherwise? What, exactly, is a crow’s grasp of physics? For the answers to such questions, author and animal researcher Jo Wimpenny takes us into the field, the zoo and the lab.

Many animals in Aesop’s stories align with the biologies of their flesh-and-blood counterparts. Studies confirm that a dog like the one in “The Dog and Its Shadow” would mistake its own reflection for a rival. But other fables depict animals in ways that contradict science. The asses of Aesop, for example, never display the patient, gentle competence frequently observed in the world’s donkey species. And sometimes the answer to whether Aesop got things wrong is trickier. To judge the accuracy of the monkeys that “ape” humans in “The Monkey and the Fisherman,” for example, scientists would need to first agree on what imitation even is—a controversy still unresolved despite a century of research and discourse.

Along the way, Wimpenny introduces us to vivid characters—human and otherwise—from the history of animal studies. Take the Progressive Era psychologist who tested primate intelligence by studying a chimpanzee that had been taught to smoke. Or Bertie, the fastest tortoise on record, who was still 70 times slower than the average hare. Aesop’s Animals is both an intense and playful look at how humans—storytellers and scientists alike—consider the mysteries inside the creatures with whom we share this planet. —Elena Passarello

IN BRIEF

A Natural History of the Future: What the Laws of Biology Tell Us about the Destiny of the Human Species

by Rob Dunn

Basic Books, 2021 ($30)

As we face the effects of climate change, applied ecology professor Rob Dunn cautions against tightening our grip on nature by controlling it with engineering. Instead he urges cooperation with the laws of biological nature that truly govern life on Earth. Dunn’s lucid discussion offers insight for surviving climate variability: the law of corridors supports creating habitat bridges to help species flee to new homes; the law of diversity favors growing refuge plants alongside transgenic crops. With the chaos in our future unknowable yet inevitable, Dunn’s absorbing analysis advocates making the most of the few certainties we have. —Dana Dunham

Super Volcanoes: What They Reveal about Earth and the Worlds Beyond

by Robin George Andrews

W. W. Norton, 2021 ($27.95)

Robin George Andrews acknowledges that volcanoes are often destructive and terrifying. But, he writes, they’re also majestic fonts of power that might have been incubators for early life and can teach us much about our own world—and those beyond. As a trained volcanologist, Andrews is in awe of his subjects; his zeal is obvious in his descriptions of each volcano’s rocks and lava, which can sometimes verge on overwrought. But his attentive reporting will be enjoyed by both the magma-curious and anyone who just wants to wonder at some of the strangest, strongest forces in the universe. —Tess Joosse

The Arts of the Microbial World: Fermentation Science in Twentieth-Century Japan

by Victoria Lee

University of Chicago Press, 2021 ($45)

To understand the invisible gardens that give us sake and penicillin, historian Victoria Lee explores the industrialization of Japanese fermentation, shedding light on the “ ‘microbe smiths’ who seek to manage microbial interactions with society.” Lee translates a brewing motto, Onko chishin, as “find new wisdom through cherishing the old,” an apt framing for the book. This porthole into 20th-century Japan is more scholarly than narrative, but there are flashes of intrigue, too: a technician’s obsession with precision, the smell of soy sauce supplemented by amino acid, the global transport of two liters of corn steep liquor. —Maddie Bender