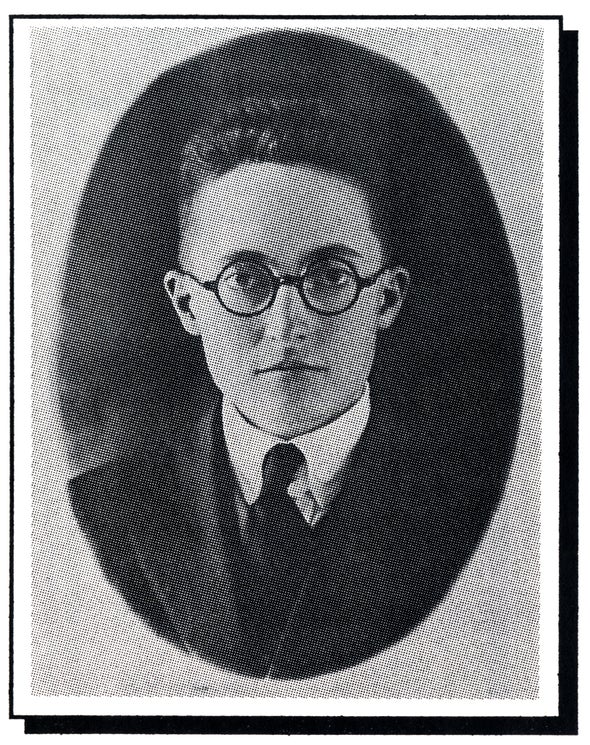

In February 1918 Alan L. Hart was a talented, up-and-coming 27-year-old intern at San Francisco Hospital. Hart, who stood at 5'4" and weighed about 120 pounds, mixed well with his colleagues at work and afterward—smoking, drinking, swearing and playing cards. His round glasses hemmed in his pensive eyes, a high white collar often flanked his dark tie, and his short hair was slicked neatly to the right. Though the young doctor’s alabaster face was smooth, he could deftly go through the motions of shaving with a safety razor. A photograph of a woman, who he had told colleagues was his wife, hung on his boarding-room wall.

Then, one day that February, Hart was gone. He left behind nothing but his razor, a stack of mail, a pile of men’s clothing—and the photograph, still gazing down from the wall.

A New Hold on Life

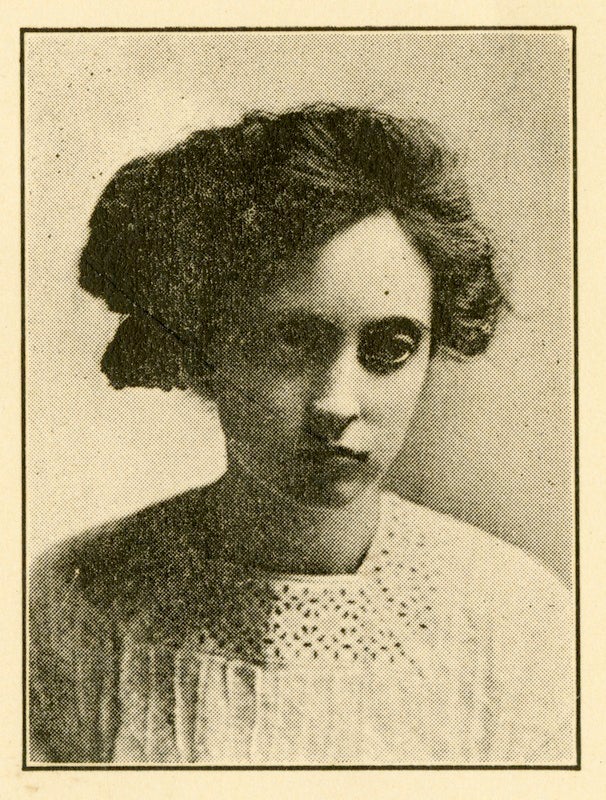

Alberta Lucille Hart, known as Lucille, was born on October 4, 1890, in Halls Summit—a lonesome part of Kansas just west of the Missouri border. The child’s father Albert, a hay, grain and hog merchant, died two years later, and his widow Edna moved with Lucille to make a new start in Oregon. They eventually settled there in the pretty town of Albany, where the Calapooia and Willamette rivers twist together like twine into a single sprawling flow.

When Lucille Hart grew old enough to learn about her father’s death, she would comfort her mother: someday, she said, she would grow up to be a man, her mother’s caretaker. Hart often secretly fantasized about marrying her female high school teacher—reveries in which she also saw herself as a man.

A talented writer, photographer and mandolinist, Hart graduated high school as salutatorian in 1908. She enrolled at Albany College, transferring to Stanford University in 1910. There, Hart entered the premedical department, joined numerous organizations and founded the school’s first ever women’s debate club. She enrolled at the University of Oregon Medical School in 1913. Four years later Hart graduated at the head of her class, the first woman to earn the coveted Saylor medal for being the top scholar in each of the school’s departments.

“Dr. Hart was a brilliant student,” a former classmate said in a 1918 edition of Spokane’s Spokesman-Review newspaper.“She had the distinction of being the only woman in the class.... She dressed often in a very mannish style, wearing particularly masculine hats and shoes and frequently tight skirts. She walked with a noticeable mannish stride.”

Hart, since childhood, had secretly identified as male and been attracted to women. Though she covertly dated several women throughout college, she largely kept her feelings hidden. Then one day, plagued by a phobia that was unrelated to her gender identity or sexual orientation, she sought help from her University of Oregon Medical School professor and doctor J. Allen Gilbert. Suspecting Hart was hiding a deeper secret, Gilbert encouraged her to confide in him. After two weeks of deliberation, Hart returned to the doctor and revealed her entire life story.

At first Hart sought psychiatric help from Gilbert, attempting to convert herself into a conventional woman. Therapy failed. Hypnosis failed. Finally, Hart halted the process—if the conversion worked, she realized, she would no longer think, feel or act like a man. And that thought repulsed her.

“Suicide had been repeatedly considered as an avenue of escape from her dilemma,” Gilbert later wrote in his 1920 case study “Homo-Sexuality and Its Treatment,” in which he referred to Hart anonymously as “H.”

“After treatment ... proved itself unavailing, she came with the request that I help her prepare definitely and permanently for the role of the male in conformity with her real nature all these years...,” Gilbert continued. “Hysterectomy was performed, her hair was cut, a complete male outfit was secured and ... she made her exit as a female and started as a male with a new hold on life and ambitions worthy of her high degree of intellectuality.”

An Undaunted Trailblazer

After transitioning, Hart was hired as an intern at San Francisco Hospital in November 1917. He lodged with a fellow male intern and hung a photograph of a woman named Inez Stark on his boarding-room wall, describing her to others as his wife. (Hart and Stark, a schoolteacher, were then romantically involved but not officially married.) Three months later, in February 1918, Hart applied for a laboratory position with physician Harry Alderson at the nearby Lane Hospital. Then something awful happened.

“Girl Poses as Male Doctor in Hospital,” roared the headline of an article in the February 5, 1918, edition of the San Francisco Examiner. “Intern Unmasked as Girl Graduate of Oregon School,” reported Portland’s Oregon Daily Journal on the same day. “Woman Poses as Man Interne in Hospital at Frisco,” echoed the Austin American on February 6.

It turned out that a former Stanford classmate had recognized Hart while he was applying for the Lane Hospital job, and had mentioned his past to someone on San Francisco Hospital’s staff. The news eventually made its way to a hospital superintendent—and then into national headlines. Hart abruptly resigned his internship and headed home to Oregon, but stood by his conviction to transition to a man.

“I had to do it,” Hart said in the March 26, 1918, edition of the Albany Daily Democrat. “For years I had been unhappy. With all the inclinations and desires of the boy I had to restrain myself to the more conventional ways of the other sex. I have been happier since I made this change than I ever have in my life, and I will continue this way as long as I live. Very few people can understand…, and I have had some of the biggest insults of my career…. I came home to show my friends that I am ashamed of nothing.”

But Hart’s hardships continued. Later in 1918 he quietly began practicing in the tiny, out-of-the-way coastal town of Gardiner, Ore.—but again, he was recognized and had to move. Hart wrote four medical novels throughout his life. His first, Dr. Mallory, is set in Gardiner and features a fictitious “Dr. Gilbert” who sheds light on Hart’s real-life hurdles: “She ‘made good’ in every way, until she was recognized…,” Dr. Gilbert says in Dr. Mallory, speaking of a female character. “Then the hounding process began.”

Between 1918 and 1927, Hart worked as a doctor in at least seven states, married and divorced Inez Stark, then graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a master’s in radiology in 1928. Hart bounced from state to state—and repeatedly, his fictional characters seemed to offer glimpses of his own struggles.

“When it came to outrunning gossip he found he couldn’t do it,” Hart wrote of Sandy Farquhar, a gay male character, in his 1936 novel The Undaunted. “He went into radiology because he thought it wouldn’t matter so much in a laboratory what a man’s personality was. But wherever he went, scandal followed him sooner or later ... His story would get around and then he’d be forced to leave.”

In The Undaunted, Farquhar commits suicide. But Hart kept going—and saved the lives of countless others.

“Hart was a pioneer in using chest x-rays to detect tuberculosis,” says Elliot Fishman, a radiologist at Johns Hopkins University. “At that point, no one was really screening for TB. Sure, if you were coughing up blood, you would get x-rays, but no one was getting ahead of the disease. One in four patients had TB. Many of them were asymptomatic. Because of Hart, doctors were able to treat patients before they had complications. And since TB is an infectious disease, he was able to separate TB patients from others to stop the spread.”

“Tuberculosis was a very stigmatizing disease,” says Cristina Fuss, a cardiothoracic radiologist and associate professor of diagnostic radiology at Hart’s medical alma mater, now known as Oregon Health & Science University. “Because of his own story, I imagine he could really empathize with someone who was struggling with being labeled. Today we still use x-rays to diagnose TB—they remain a hallmark of screening for TB. Hart was certainly a trailblazer.”

Hart worked with TB patients in Washington State and Idaho before moving to Connecticut, where he earned a master’s in public health from Yale University in 1948 at age 57. He continued his TB work in Connecticut. “Hart worked for the department of public health,” Fishman says. “TB is a public health problem. He was able to combine his interest in radiology with his interest in public health. I imagine his work helped create other programs across the country.”

Rewriting History

Hart lived out the rest of his life in West Hartford, Conn., with his second wife Edna Ruddick, before dying of heart disease at age 71 on July 1, 1962. In his will, Hart instructed an attorney to destroy the personal photographs and records he had stored in two locked boxes. But in 1976 historian Jonathan Katz identified Hart as “H” in Gilbert’s 1920 case study, and unearthed the doctor’s story. Six years later Edna Ruddick Hart died, leaving the majority of her estate to the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon in honor of her late husband.

“When uncovering the story of someone from the past, especially someone from the early 20th century—someone who, today, we would identify as transgender,” says Peter Boag, a history professor at Washington State University and an award-winning LGBT historian, “we have to remember that, although the trans identity is recent in history, people often forget that trans people lived in the past. Uncovering the story of any trans person is not just something that affirms trans people’s existence today. It rewrites our history.”

Editor’s Note: Up until 1917, Hart publicly identified as Alberta Lucille Hart and used the pronoun “she.” After transitioning that year, Hart publicly identified as Alan L. Hart and used the pronoun “he.”