True to their name, glasswing butterflies sport remarkably transparent wings that help them hide in plain sight. New work shows how narrow, bristlelike scales and a waxy, glare-cutting coating combine to make parts of the wings nearly invisible.

Most moths and butterflies get their vibrant colors from flat scales that tile the wing surface like shingles; relatively few species have clear wings. Nipam Patel, an evolutionary and developmental biologist at the Marine Biology Laboratory, first investigated the wings of several such species with his students in an embryology class. “It was amazing,” he says, “because they found every way you could imagine to have a transparent wing—from having see-through scales to no scales at all.”

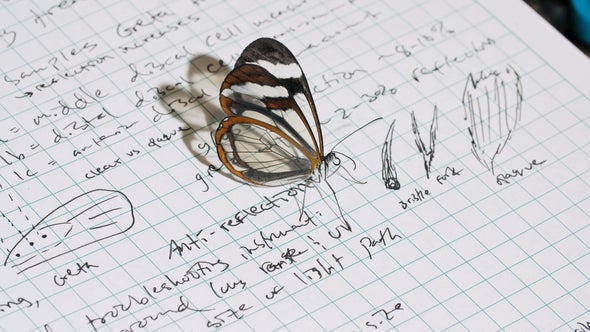

Previous studies that explored the structural diversity and optical properties of wing transparency involved adult specimens held in museums, so the developmental processes underlying transparency were largely unknown. For a new study in the Journal of Experimental Biology, Patel and his colleagues raised glasswing butterflies and tracked their wing development, creating the first detailed time-series record of the process. Their work shows that glasswing butterflies grow sparse, narrow bristles for the clear patches as well as broader scales (top right), using fewer scale precursor cells than other butterflies do.

Colorless wings can be shiny, so butterflies have evolved ways of reducing reflected light. Using powerful electron microscopes, the researchers took a closer look at nanopillars—minuscule structures that are known to prevent glare—scattered on the glassy wings' surface. The team saw that a regularly spaced layer of nanopillars made from chitin, a fibrous substance found in insect exoskeletons, supports an irregular layer of nanopillars made from a waxy chemical that significantly lowers the amount of reflected light. The researchers say these findings could inspire new antireflective materials.

The study also sets the groundwork for future efforts to pinpoint the genetic mechanisms by which butterfly and moth color (or the lack thereof) evolves, says Cornell University ecologist Robert Reed, who was not involved with the study. “Scales are the evolutionary innovation that marks moths and butterflies,” Reed notes, “so it's kind of remarkable that there has been a reversion of sorts [from color to colorless] in some species.”