With smoke from blazing forests in the U.S. West tinting skies ochre this year and last, residents and researchers alike asked, “How much worse can fire seasons get?” University of Montana fire paleoecologist Philip Higuera has spent his career trying to determine the answer by looking at history. “If we’re all wondering what happens when our forests warm up,” he says, “let’s see what happened in the past when they warmed up.”

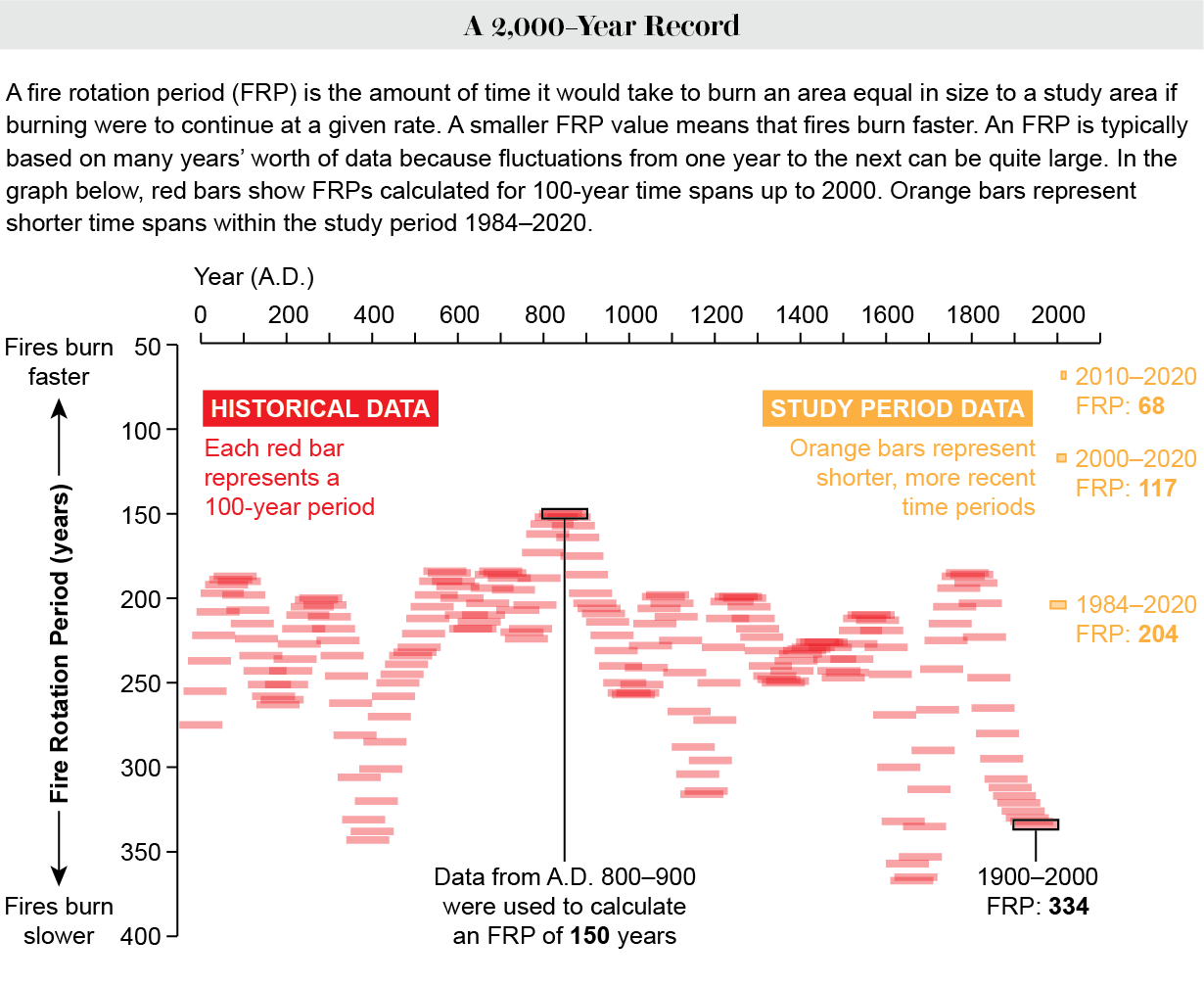

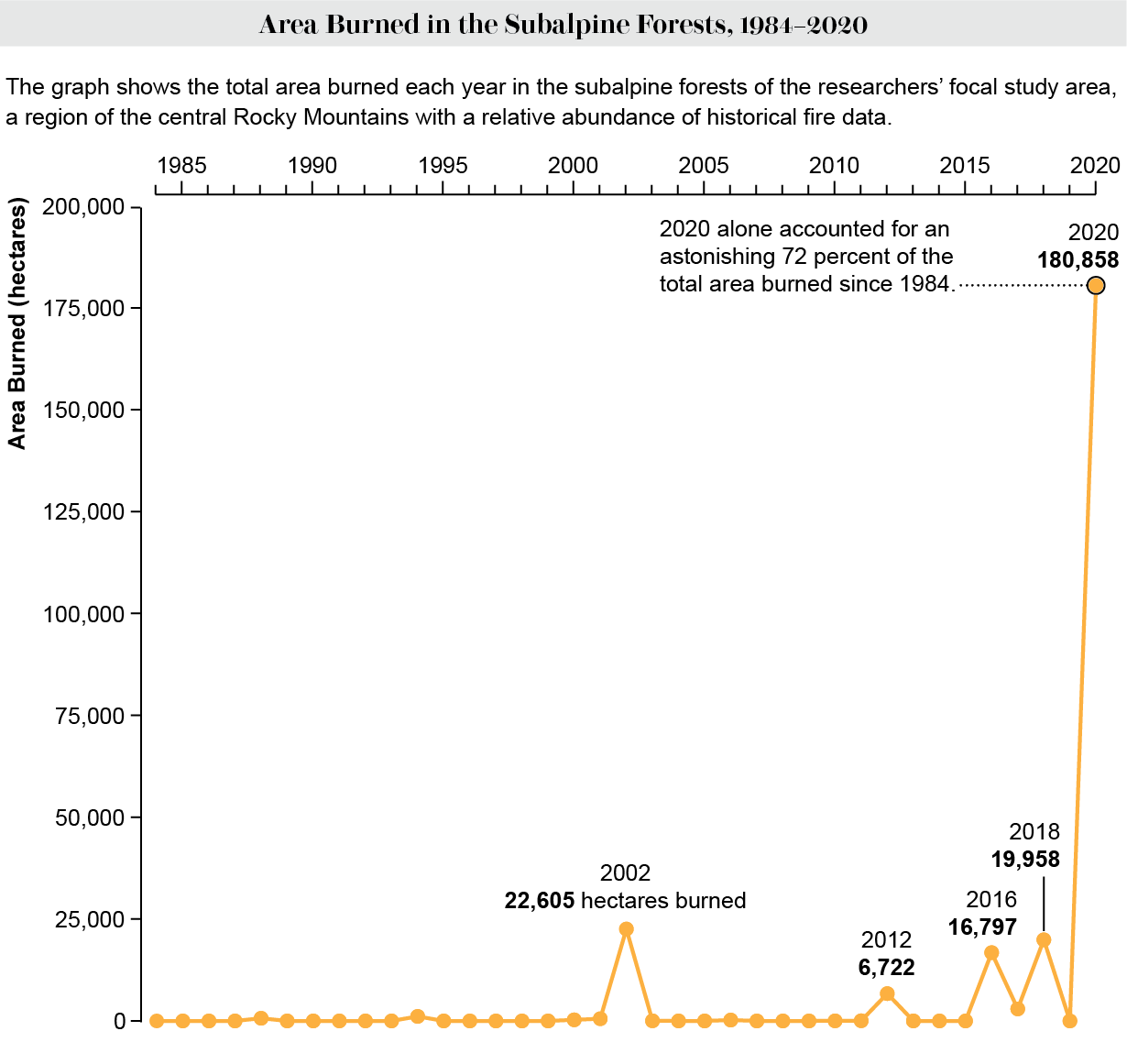

The central Rocky Mountains’ subalpine forests grow in cool, wet conditions and burn less readily than their lowland counterparts. To find out how frequently these tough woodlands nonetheless have caught fire through the ages, Higuera and his colleagues combined records from modern satellite-observed fires, fire scars in tree rings from the 1600s onward, and flecks of charcoal that settled in lakes over thousands of years. The study found that from 2000 to 2020, the forests burned 22 percent faster than they did during an unusual warming period that started in A.D. 770 and saw the area’s highest temperatures prior to the 21st century. Most of this burn rate increase, as well as 72 percent of the total area burned between 1984 and 2020, resulted from fires in 2020 alone.

Overall, these forests have not burned frequently—until the past two decades. The gap between extreme fire years in the U.S. is narrowing as the climate warms, and Higuera does not think this pattern will reverse any time soon. The new research is detailed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Higuera finds the recent unprecedented fire seasons unsurprising but still agonizing. “I’ve spent 20 years writing about this,” he says. “But I have not spent 20 years thinking about how this would feel.”

This work shows that the past may no longer guide us when it comes to understanding and handling wildfires, says Humboldt State University environmental geographer Rosemary Sherriff, who was not involved in the study. “We have to accept that we’re going to see an increase in fire activity,” she says. “We have to adapt to the new norm.”

Many communities hit by recent wildfires have fire-protection plans, Higuera adds, but “they’re based on our expectations that these forests burn once every few centuries. That’s not where we are. That’s not where we’re going.”