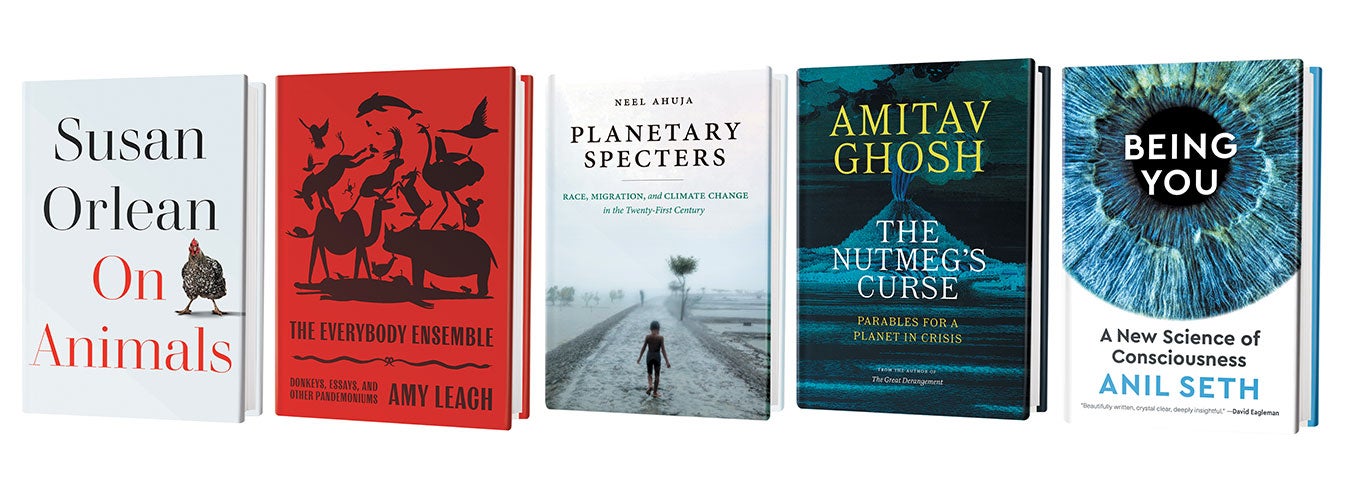

On Animals

Susan Orlean

Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, 2021 ($28)

In On Animals, a new collection of old essays, veteran journalist Susan Orlean is almost the obverse of wonder-seeking naturalists like David Attenborough. Her focus is not on wild creatures and their swiftly disappearing worlds but on animals that live in human-dominated spheres: pets, working animals, and those kept as barnyard companions, livestock, or curiosities. Her subjects are the familiar denizens of the home, farm, zoo and marketplace.

Orlean explores the human machinations around show dogs and celebrity megafauna such as captive giant pandas and the movie star orca Keiko of Free Willy fame. She tells the unsettling saga of an American woman who kept numerous tigers, written long before the airing of the notorious series Tiger King. The differences between mules and donkeys are illuminated here, as are the decline and fall of pack animals in the armed forces and the poignancy of a young girl's devotion to her homing pigeons.

Orlean deftly captures some of the ways in which categories like “pet” and “revenue source” or “food” overlap, sometimes painfully. And how in other cases, such as donkeys in Morocco's medinas, working animals are seen as machines and unmourned when, after years of devoted service, they die. Some readers may be startled by her rosy account of a meet and greet with a privately owned African lion, brought to her New York apartment as an apparently charming Valentine's Day surprise; it doesn't stop to contemplate, as her story “The Lady and the Tigers” does, the ethical dimensions of personal wild-animal ownership. But in general, these well-researched and readable essays—originally published in the New Yorker and Smithsonian Magazine beginning in 1995—open onto a world of troubled human relationships with charismatic beasts.

In her introduction, a piece called “Animalish”—the only newly written material in the collection—Orlean describes her lifelong interest in animalkind and speculates that she has a rare affection for it. But there's little evidence in the book of the author as an outlier. Clearly, she loves dogs, chickens, horses, and other long-time familiar companions and has gone to great lengths to make caring for many of them a focus of her wide-roaming investigative life. But the proposition that her affinity is outlandish lands with an oddly unexamined weight. Is a fondness for other animals strange?

Even in a culture willfully detached from the wild, animal sign is visible everywhere. I rarely enter a home, office or store that doesn't contain a simulacrum of one of them—usually several. Animal forms, references and mimicries hover all around us, even in places where no living nonhuman animals are present (at least, beyond the miniature and microscopic). They populate our language with their richness, diversity and color and play a critical role in helping us raise our children.

So when Orlean asks the question, in “Animalish,” of whether her life among the other animals and her yearning for their company is atypical, I find myself wishing she'd answered the question in greater depth—wishing that, given this collection's central theme, she'd examined how humanness is constructed through and around the existence of nonhuman animals. How our notions of personhood are built on the vast foundation of our extensive evolutionary and social history with the other species that define our lived experience. In a time of pressing and accelerating biodiversity crisis, it seems more urgent than ever that we grapple with the implications of our use and abuse of other life-forms, whether domesticated or wild—with how our love for them is mediated by, and subsumed into, our exploitation of their bodies and habitats. With how and why our culture has taught us that other animals are little more than useful idiots and that, therefore, our love of them is childish, hobbyistic or weird. When in fact, our stories, homes and minds are furnished with the artifacts of a far deeper love.

The best writing in On Animals—about Keiko the orca, say, or about donkeys or about Biff the prizewinning boxer—occurs where the mundane meets the tragic, at the crossroads between our compulsion to care for and be near animals and our dawning realization that those animals are always, finally, beyond our sphere of nurturing and control.—Lydia Millet

Reveling in Nature's Eccentricities

The Everybody Ensemble: Donkeys, Essays, and Other Pandemoniums

by Amy Leach

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021 ($26)

Amy Leach's latest effort—an expansive, thought-provoking reflection on the natural world—is a worthy successor to her celebrated first book, Things That Are. A winner of the Whiting Award and the Pushcart Prize, Leach charms even as she challenges the reader with this new collection.

In the titular essay, a choir director encourages everyone on the “Existence Boat” to raise their voices in a joyous cacophony of Being. It is an apt kickoff for a book so planetary in scope. The “Pandemoniums” that follow cover everything from the chaotic mindfulness of Beanstan, Leach's unhinged Pomeranian, to Elon Musk's recent spaceflight, the premise of which she rejects on the basis of her loyalty to Earth: “Yes to the Earth, my Earth, for I do not hope to find a better where.

But Leach's love for Earth is not unexamined. She often criticizes humanity's reductive view of animals, noting our propensity to collapse them into anatomy or taxonomy and rejecting our tendency to use them as religious symbols. (One example of the latter is “Dogness defies dogma.”) Instead, Leach argues, our animal brethren's identity is inherent, and they stand for nothing but themselves.

In “Non Sequiturs,” she illustrates the application of this through an animal- oriented exegesis of the Book of Job, highlighting how God “brings lions and lightning and various other non sequiturs, like donkeys” to answer Job's many questions. “Perhaps,” Leach remarks, “we could try his rhetorical method ourselves.” And she does just that, illuminating her essays with a dizzying array of nature references: some household names (eagles, grapes, seahorses), others less so (strawberry frogs, Gegenschein, Flabellina). After importing them, she does not just set them blithely down, but rather she rubs them together with her point until insights shoot like sparks. If they are non sequiturs, they still forge links via revelation rather than relatedness.

Leach's essays are passionate, but they refresh more than burn. While breathtakingly sophisticated in their content, their tone recalls the best and most beloved children's books: playful but gentle, earnest without being naive, reverberant with ontological wonder. Fusing poetry and biology, philosophy and commentary, this collection offers something for everyone on the Existence Boat. —Dana Dunham

Planetary Specters: Race, Migration, and Climate Change in the Twenty-First Century

by Neel Ahuja

University of North Carolina Press, 2021 ($95)

When journalists and policy makers discuss migration crises, Neel Ahuja writes, they tend to blame the amorphous boogeyman of “climate change” without interrogating the web of underlying roots. In Planetary Specters, he tugs at the thread—namely, oil—that connects much of the global economy to unravel how capitalist production doesn't just generate cascading conditions for warming but creates a “shrinking horizon of habitation” for the much of the world's poor. There are no easy answers, of course. But as the planet continues hurtling toward disaster at breakneck speed, Ahuja presents a convincing framework for understanding environmental racism. —Tess Joosse

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis

by Amitav Ghosh

University of Chicago Press, 2021 ($25)

In this essayistic follow-up to his 2016 book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh sees the seeds of our climate emergency in the violent 17th-century occupation of the nutmeg plantations of the Banda Islands in Indonesia. To Ghosh, the policies of the Dutch East India Company illustrate “the unrestrainable excess that lies hidden at the heart of the vision of world-as-resource—an excess that leads ultimately not just to genocide but an even greater violence, an impulse that can only be called ‘omnicide,’ the desire to destroy everything.” Ghosh finds hope in the promise of renewable energy and the “vitalist politics” of Greta Thunberg, the activists of Standing Rock, and others. —Seth Fletcher

Being You: A New Science of Consciousness

by Anil Seth

Dutton, 2021 ($28)

Being You is a logically rigorous (verging on tedious) treatise on consciousness. An acclaimed British neuroscientist, Anil Seth handily summarizes the knowns and significantly more numerous unknowns of our current understanding about how “the inner universe of subjective experience relates to, and can be explained in terms of, biological and physical processes.” He is just as likely to cite Immanuel Kant as recently published studies to support his claims about personhood and perception. But Seth's vivid descriptions of real-life experimental setups—such as an artificial neural network creating visual hallucinations of dogs in virtual reality—prove more imaginative and compelling than philosophical hypotheticals of false selves and teleportation. —Maddie Bender