Listen to an audio version of the article.

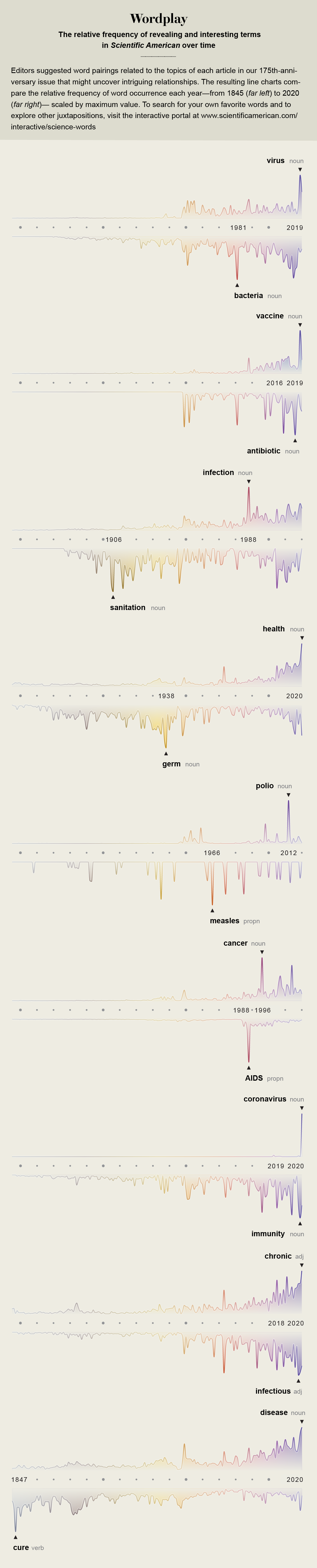

In 1972 the distinguished virologist Frank Macfarlane Burnet looked back over medical progress made in the 20th century with considerable satisfaction, surveying it for the fourth edition of the book Natural History of Infectious Disease. That very year routine vaccination against smallpox had ceased in the U.S., no longer needed because the disease had been eliminated from the country. During the previous year the combined vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella had been licensed, and four years before, in 1968, a pandemic of influenza had been quelled by a new vaccine formula. In 1960 Albert Sabin had delivered an oral vaccine against polio, and five years before that Jonas Salk had produced the first polio shot, preventing the dreaded paralysis that crippled children every summer. Since the time of World War II, drug development had delivered 12 separate classes of antibiotics, beginning with natural penicillin and ending seemingly forever the threat of deadly infections from childhood diseases, injuries, medical procedures and childbirth.

A few pages from the end of his book (co-authored with David O. White), Burnet made a bold prediction: “The most likely forecast about the future of infectious disease,” he wrote, “is that it will be very dull.”

Burnet was an experienced scientist who had shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960 for pioneering ideas about the way people developed immune reactions. And at 73 he had lived through devastating epidemics, including the planetspanning flu pandemic of 1918 while he was a university student in Australia. So he had seen a lot of advances and had played a role in some of them. “From the beginnings of agriculture and urbanization till well into the present century infectious disease was the major overall cause of human mortality,” he wrote on the book’s first page. “Now the whole pattern of human ecology has, temporarily at least, been changed.”

Four years after Burnet made his optimistic prediction, the headmaster of a village school in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo collapsed with an unexplained bleeding disorder and died, the first recognized victim of Ebola virus. Nine years after his forecast, in 1981, physicians in Los Angeles and an epidemiologist at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention diagnosed five young men in Los Angeles with an opportunistic pneumonia, the first signal of the worldwide pandemic of HIV/AIDS. In 1988 the gut bacterium Enterococcus, a common source of hospital infections, developed resistance to the last-resort antibiotic vancomycin, turning into a virulent superbug. And in 1997 a strain of influenza designated H5N1 jumped from chickens to humans in a market in Hong Kong, killing one third of the people it infected and igniting the first of multiple global waves of avian flu.

Those epidemics represent only a few of the infectious disease eruptions that now occur among humans every year, and efforts to stem them have taken on a renewed and urgent role in modern medicine. Some of these contagions are new to our species; others are resurgent old enemies. Sometimes their arrival sparks small outbreaks, such as an eruption of H7N7 avian flu in 2003 among 86 poultry-farm workers in the Netherlands. Now a never-before-seen illness, COVID- 19, has caused a global pandemic that has sickened and killed millions.

None of these scenarios matches what Burnet envisioned. He thought of our engagement with infectious diseases simply as one mountain that we could climb and conquer. It might be more accurate to understand our struggle with microbes as a voyage across a choppy sea. At times we crest the waves successfully. In other moments, as in the current pandemic, they threaten to sink us.

It is difficult, under the weight of the novel coronavirus, to look far enough back in American history to perceive that—surprisingly—freedom from infectious disease was a part of the early New England colonists’ experience. Beginning in the 1600s, these people fled English and European towns drenched in sewage and riven with epidemics where they might be lucky to live to their 40th birthday. They found themselves in a place that felt blessed by God or good fortune where a man—or a woman who survived childbearing—could, remarkably, double that life span.

This was true, of course, only for the colonizers and not for the Indigenous Americans whom they displaced. The Spanish who arrived in Central and South America about a century earlier, and other European colonists who followed to the North, brought diseases so devastating to the precontact population that researchers have estimated 90 percent of the existing inhabitants were killed. Nor was it true for enslaved people brought to American shores, whose lives were cut short by abuse in the South’s plantation system.

New Englanders before the 19th century, however, “had a very strange and unusual experience with infectious diseases,” says David K. Rosner, a historian and co-director of the Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health at Columbia University. “When infections hit, and they did hit—smallpox, yellow fever—they were largely very localized and of relatively short duration.”

At the time and through the early 1800s, disease was understood as a sign of moral transgression, a visitation meant to guide an erring population back to righteousness. In 1832 the edge of a worldwide pandemic of cholera washed up on the East Coast of the U.S., carried into port cities by ships plying trade routes. The governors of a dozen states declared a mandatory day of prayer and fasting. In New York the well-off fled the city for the socially distanced countryside, blaming the poor left behind for their own misfortune. A letter preserved by the New-York Historical Society, written by its founder, captures the callousness of some wealthy people: “Those sickened … being chiefly of the very scum of the city, the quicker [their] dispatch the sooner the malady will cease.”

Cholera was a global devastation, but it was also a doorway to our modern understanding of disease. Dogma held that its source was miasmas, bad air rising from rotting garbage and stagnant water. As late as 1874—20 years after physician John Snow traced the source of a London cholera outbreak to a neighborhood’s well and halted it by removing the pump handle—an international conference on the disease declared that “the ambient air is the principal vehicle of the generative agent of cholera.” It was not until 10 years later, when bacteriologist Robert Koch found identical bacteria in the feces of multiple cholera victims in India and reproduced the bacterium in a culture medium, that a microbe was proved to be the cause. (Koch was not aware that Italian bacteriologist Filippo Pacini had made the same observations in the year when Snow took the handle off the pump.)

This explanation for the source of cholera became one of the foundations of germ theory. The concept that disease could be transmitted and that the agents of transmission could be identified—and possibly blocked—transformed medicine and public health. The idea ignited a burst of innovation and civic commitment, a drive to clean up the cities whose filthy byways allowed disease-causing microbes to fester. Towns and states established municipal health departments and bureaus of sanitation, built sewer systems and long-distance water supplies, regulated food safety and ordered housing reform.

These improvements tipped industrial nations toward what would later be called the epidemiological transition, a concept coined by Abdel Omran in 1971 to describe the moment when deadly infections would retreat and slow-growing chronic diseases could become society’s priority. Science started a seemingly unstoppable climb up the mountain of 20th-century achievement: viral identification, vaccine refinement, the development of antibiotics, the introduction of immunotherapies, the parsing of the human genome. Life expectancy in the U.S. rose from an average of 47 years in 1900 to 76 years toward the end of the century. The last case of smallpox, the only human disease ever eradicated, was recorded in 1978. The Pan American Health Organization declared its intention to eliminate polio from the Americas in 1985. The future seemed secure.

It was not, of course. In October 1988, in this magazine, Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier wrote: “As recently as a decade ago it was widely believed that infectious disease was no longer much of a threat in the developed world. The remaining challenges to public health there, it was thought, stemmed from noninfectious conditions such as cancer, heart disease and degenerative diseases. That confidence was shattered in the early 1980’s by the advent of AIDS.”

Gallo and Montagnier were co-discoverers of the HIV virus, working on separate teams in different countries. When they wrote their article, there had been more than 77,000 known cases of AIDS on the planet. (There are 76 million now.) As the researchers noted, recognition of the new illness punctured the sense of soaring assurance that infectious diseases had been conquered. Four years after Gallo and Montagnier wrote, 19 eminent scientists gathered by the Institute of Medicine (now part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine) broadened the point in a sober book-length assessment of what they termed “emerging infections.” Scientists and politicians had become complacent, they said, confident in the protection offered by antibiotics and vaccines and inattentive to the communicable disease threats posed by population growth, climate warming, rapid international travel, and the destruction of wild lands for settlements and mega-farms.

“There is nowhere in the world from which we are remote,” the group warned, “and no one from whom we are disconnected.” The scientists recommended urgent improvements in disease detection and reporting, data sharing, lab capacity, antibiotics and vaccines. Without those investments, they said, the planet would be perpetually behind when new diseases leaped into humans and catastrophically late in applying any cures or preventions to keep them from spreading.

Their warning was prescient. At the time of their writing, the U.S. was recovering from its first major resurgence of measles since vaccination began in the 1960s. More than 50,000 cases occurred across three years when epidemiological models predicted that there should have been fewer than 9,000. The year after the Institute of Medicine’s report was published, five healthy young people collapsed and died in the Southwestern U.S. from a hantavirus passed to them by deer mice. In 1996 researchers in Chicago discovered that antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus bacteria had leapfrogged from their previous appearances in hospitals into everyday life, causing devastating illnesses in children who had no known risks for infection. Across health care, in urban life and in nature, decades of progress seemed to be breaking down.

“We forgot what rampant infectious disease looked like,” says Katherine Hirschfeld, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, who studies public health in failing states. “Science built us a better world, and then we got cocky and overconfident and decided we didn’t have to invest in it anymore.”

But unlike illnesses in the past—cholera epidemics in which the rich fled the cities, outbreaks of tuberculosis and plague blamed on immigrants, HIV cases for which gay men were stigmatized—infections of today do not arrive via easy scapegoats (although jingoistic politicians still try to create them). There is no type of place or person we can completely avoid; the globalization of trade, travel and population movement has made us all vulnerable. “We cannot divide the world anymore into countries that have dealt with infectious disease successfully and those that are still struggling,” Hirschfeld says. “Countries have enclaves of great wealth and enclaves of poverty. Poor people work for rich people, doing their landscaping, making things in their factories. You cannot wall off risk.”

The planet that slid down the far side of the 20th century’s wave of confidence is the planet that enabled the spread of COVID-19. In the five years before its viral agent, SARS-CoV-2, began its wide travels, there were at least that many warnings that a globally emergent disease was due: the alerts appeared in academic papers, federal reports, think-tank war games and portfolios prepared at the White House to be handed off to incoming teams. The novel coronavirus slipped through known gaps in our defenses: it is a wildlife disease that was transmitted to humans by proximity and predation, spread by rapid travel, eased by insufficient surveillance, and amplified by nationalist politics and mutual distrust.

We were unprepared, with no vaccine or antiviral. In past epidemics of coronaviruses, such as SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2012, scientists had begun work on vaccines, but funding and interest dried up as the outbreaks waned. If research had continued, the current emergency might have been shortened. Preventions and pharmaceuticals were the stellar achievements of the 20th century, but among scientists and physicians who deal with emerging diseases, there is a sense that attempts to repeat such successes will not be sufficient to save us. What is equally urgent, they argue, is attending to and repairing the conditions in which new diseases arise.

“Poverty has more impact than any of our technical interventions,” says Peter J. Hotez, a physician and vaccine developer and founding dean of the Baylor University National School of Tropical Medicine. “Political collapse, climate change, urbanization, deforestation: these are what’s holding us back. We can develop all the vaccines and drugs we want, but unless we figure out a way to deal with these other issues, we’ll always be behind.”

Evidence for Hotez’s statement is abundant in the toll of those who have suffered disproportionately in the current pandemic—people who rely on urban transit, live in public housing or nursing homes, or are subject to the persistent effects of structural racism. What has made them vulnerable is not primarily a lack of drugs or vaccines. “My hospital is buried in COVID-19 patients,” said infectious disease physician Brad Spellberg, chief medical officer at Los Angeles County–University of Southern California Medical Center, one of the largest public hospitals in the U.S., in mid-2020. “We serve a community of people who cannot physically distance. They are homeless, they are incarcerated, they are working poor living with a family of four in one room.”

The term often used to denote what Hotez and Spellberg are describing is “social determinants of health.” It is an unsatisfying phrase that lacks the muscular directness of “shot” and “drug,” but it is a crucial and also measurable concept: that social and economic factors, not just medical or innate immunological ones, strongly influence disease risk. Negative social determinants include unsafe housing, inadequate health care, uncertain employment and even a lack of political representation. They are the root cause of why the U.S., the richest country on Earth, has rapidly rising rates of hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and parasitic and waterborne infections, as reported in Scientific American in 2018—infections that first arise among the poor and unhoused but then migrate to the wealthy and socially secure. As research by British epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett has shown, unequal societies are unhealthy ones: the larger the gap in income between a country’s wealthiest and poorest, the more likely that country is to experience lower life expectancy and higher rates of chronic disease, teen births and infant mortality. That phenomenon goes a long way toward explaining why COVID-19 wreaked such devastation in New York City, one of the most financially unequal cities in the country, before the city government applied the brute-force tool of lockdown and regained control.

Lockdowns are effective, but they cannot be sustained indefinitely, and they carry their own costs of severe mental health burdens and of keeping people from health care not related to the virus. And although quarantines may keep a pathogen from spreading for a while, they cannot stop a virus from emerging and finding a favorable human host. What might prevent or lessen that possibility is more prosperity more equally distributed—enough that villagers in South Asia need not trap and sell bats to supplement their incomes and that low-wage workers in the U.S. need not go to work while ill because they have no sick leave. An equity transition, if not an epidemiological one.

It is difficult to enumerate features of this more protected world without them sounding like a vague wish list: better housing, better income, better health care, better opportunities. Still, changes that some places around the globe enacted as defenses against current infection might make future infections less likely. Closing streets to encourage biking as Lisbon did, turning parking spaces into café spaces as has happened in Paris, and creating broadband capacity for remote working and shifting health care to telemedicine, both done in the U.S.—these adaptations sound like technological optimism, but they could help us construct a society in which people need not crowd into unsafe urban spaces and in which income can be detached from geography.

It is certainly also necessary to re-up the investments in preparedness that the Institute of Medicine rebuked the U.S. for dropping almost 30 years ago. “We need to think about this with an insurance mindset,” says Harvey Fineberg, a physician and president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, who was president of the institute when it prepared a 2003 follow-up to its warning. “If your house doesn’t burn down, you don’t bang your head on the wall on December 31 and say, Why did I buy that fire insurance? We buy insurance proactively to prevent the consequences of bad things that happen. That is the mindset we need to adopt when it comes to pandemics.”

The U.S. responded to the coronavirus with an extraordinary federally backed effort to find and test a vaccine in time to deliver 300 million doses by early 2021. This was a tremendous aspiration given that the shortest time in which a vaccine has ever been produced from scratch is four years (that vaccine was against mumps). There is no question that medical science is much better equipped than it was when Burnet was writing in the 1970s; Natural History of Infectious Disease came out before monoclonal antibody drugs, before gene therapy, before vaccines that could target cancers rather than microbes. The apotheosis of such work may be the development of chimeric antigen receptor T cell, or CAR-T, therapies, which debuted in 2017 and reengineer the body’s own specialized immune system cells to combat cancers.

But CAR-T is also a sign of how concern for infectious diseases has slid into a trough of disregard. CAR-T therapies help a rare few patients at an extraordinary cost—their price before any insurance markup hovers around $500,000—whereas antibiotics, which have saved millions from death by infection, have slipped into peril. Most of the major companies that were making antibiotics in the 1970s—Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis, among others—have left the sector, unable to make adequate profits on their products. In the past few years at least four small biotechnology companies with new antibiotic compounds went bankrupt. This happened even though antibiotics are a crucial component of medicine—and now it is clear that they will be needed for some COVID-19 patients to cure severe pneumonias that follow the initial viral infection.

Better structures for preparedness—disease surveillance, financial support for new drugs and vaccines, rapid testing, comprehensive reporting—will not by themselves get us to a planet safer from pandemics any more than car-free streets and inexpensive health care will. But they could give us a place from which to start, a position in which we are relatively more secure as a society, relatively more safe from known diseases, and more likely to detect previously unknown threats and to innovate in response to them.

Rosner, the historian, looks back to the explosive energy of the Progressive Era and wonders what a post-COVID equivalent might be. “In the 19th century we built entire water systems, we cleaned every street in cities,” he says. “We have so constricted our vision of the world that it seems we can’t address these issues. But there are moments in past crises when we have let the better angels in our society come to the fore: after the Great Depression, in the New Deal. It’s not impossible.”