The biggest debate among experts on the Anthropocene is when, exactly, a geologic epoch marked by humanity's influence began. As an astrobiologist who studies major historical transitions in planetary evolution, I am more interested in another question: When, and how, will the Anthropocene end?

Epochs are relatively short periods of geologic time. Much more consequential are the boundaries separating the geologic timescale's longest phases, the billion-year-scale chunks of history called eons. These transitions left the world permanently and profoundly changed. From the hellish conditions of the Hadean eon, Earth shifted to a cooler, quieter Archean eon that nurtured the emergence of life. During the Proterozoic eon, some of those microbes became a disruptive, planet-altering force, flooding the atmosphere with photosynthetic oxygen. This change in atmospheric chemistry poisoned much of the biosphere, but it also led to the flourishing of complex multicellular life, ushering in our current eon, the Phanerozoic.

The Anthropocene may be the beginning of another fundamental transition. This fifth eon could be defined by a radically new type of global change in which cognitive processes—the thoughts, deeds and creations of human beings—become a key part of the functioning of our planet. I propose we call this potential new eon the Sapiezoic, for “wise life.” For the first time in Earth's history, a self-aware geologic force is shaping the planet.

But an epoch only becomes an eon if it endures for hundreds of millions of years or longer. For that to happen, we have to endure that long. Are we up to it?

What is the chance Homo sapiens will survive for the next 500 years?

I would say that the odds are good for our survival. Even the big threats—nuclear warfare or an ecological catastrophe, perhaps following from climate change—aren't existential in the sense that they would wipe us out entirely. And the current bugaboo, in which our electronic progeny exceed us and decide they can live without us, can be avoided by unplugging them.”

—Carlton Caves Distinguished Professor Emeritus in physics and astronomy at the University of New Mexico

Avoiding Extinction

Our most immediate challenges over the next century are to stabilize our population and to construct energy and agricultural systems that can provide for us without wrecking natural systems. There is no doubt that we will shift away from fossil fuels, but the speed with which we do so may determine whether the displacement and suffering caused by climate disruption in the 21st century will rival or surpass those caused by the wars, revolutions and famines of the 20th.

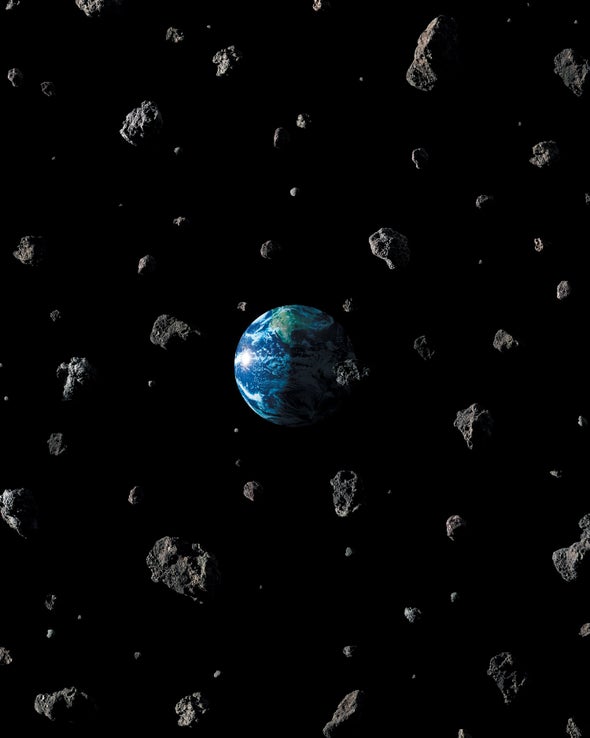

Anthropogenic global warming is waking us up to our inescapable role as planetary-scale operators, but it is not the only large-scale, long-term challenge we will face. Over the coming centuries, for example, we will need to devise effective defenses against dangerous asteroids and comets. A much smaller object than the 10-kilometer rock that did in the dinosaurs could devastate human civilization. Soon we will have catalogued most of the dangerous Earth-crossing asteroids. But a dark and dangerous comet can always come screaming from the fringes of the solar system with little warning. We should be ready to deflect such an interloper.

On a longer timescale—tens of thousands of years—we must learn how to prevent natural climate changes that dwarf the present warming spike. Civilization has developed during what is essentially a 10,000-year summer, a multimillennial period of unusually warm and stable climate. This will not last—unless we decide it should. Over tens of thousands to many millions of years, Earth goes through cycles of glaciation and global warming. Another ice age would wipe out most of our agriculture and thus our civilization while causing the extinction of countless other species. Geoengineering techniques to artificially cool (or heat) the planet could free the Sapiezoic eon from these destructive fluctuations in climate.

Most discussions of geoengineering center on desperate short-term fixes for our self-inflicted climate woes, but our present ignorance of the complexities of Earth's climate makes such attempts exceedingly risky. Geoengineering is best regarded as a long-term project for the distant future, when we know much more about the Earth system and when that system will be pushed to the brink either by intrinsic climate fluctuations or—much further still in the future—by our home star reaching its senescence.

Stars like the sun grow more luminous as they age, meaning that a few billion years from now, our oceans will boil away like Venus's did billions of years ago. Fortunately, this is a long way off. Provided we overcome nearer-term existential threats, we will have plenty of time to work on that problem. Perhaps we could somehow rejuvenate the sun, move Earth to a wider orbit or partially shade our planet. Alternatively, we may decide to emigrate to another, younger star system.

Are we any closer to preventing nuclear holocaust?

Since 9/11, the U.S. has had a major policy focus on reducing the danger of nuclear terrorism by increasing the security of highly enriched uranium and plutonium and removing them from as many locations as possible. A nuclear terrorist event could kill 100,000 people. Three decades after the end of the cold war, however, the larger danger of a nuclear holocaust involving thousands of nuclear explosions and tens to hundreds of millions of immediate deaths still persists in the U.S.-Russian nuclear confrontation.

“Remembering Pearl Harbor, the U.S. postured its nuclear forces for the possibility of a bolt-out-of-the-blue first strike in which Russia would try to destroy all the U.S. forces that were targetable. We don't expect such an attack today, but each side still keeps intercontinental and submarine-launched ballistic missiles carrying about 1,000 warheads in a launch-on-warning posture. Because the flight time of a ballistic missile is only 15 to 30 minutes, decisions that could result in hundreds of millions of deaths would have to be made within minutes. This creates a significant possibility of an accidental nuclear war or even hackers causing launches.

“The U.S. does not need this posture to maintain deterrence, because it has about 800 warheads on untargetable submarines at sea at any time. If there is a nuclear war, however, U.S. Strategic Command and Russia's Strategic Missile Forces want to be able to use their vulnerable land-based missiles before they can be destroyed. So the cold war may be over, but the Doomsday Machine that came out of the confrontation with the Soviets is still with us—and on a hair trigger.

—Frank von Hippel Emeritus professor at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and co-founder of Princeton University's Program on Science and Global Security

The World in Our Hands

If intelligence can arise as a self-aware geologic force here, then it can probably emerge elsewhere. As we peer deeper into the universe, we may find that there are three kinds of worlds: dead, living and sapient. Of course, there is a chance that ours is the only sapient world in a vast and silent cosmos. If so, then in addition to shaping the well-being of all future life on Earth, our choices dictate the fate of all sentient life in the universe. That is quite a responsibility.

History offers hope that we can handle it. One of humanity's most ancient hallmarks is our capacity to respond to existential threats. We seem to have survived a genetic bottleneck around 75,000 years ago, when climate change, probably caused by a “volcanic winter,” led to the death of most humans. Earlier, between 200,000 and 160,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans arose in Africa after a devastating ice age almost eradicated all our predecessors. The secret to our ancestors' survival was probably our use of language to develop new modes of social cooperation.

Right now we are struggling to find our way through a dawning Anthropocene. If we endure, however, we could learn to protect Earth's biosphere almost indefinitely. In the long run, we could prove to be the best thing that ever happened to planet Earth.