Some gestures can be understood almost anywhere: pointing to direct someone’s attention, for instance. New research shows that certain vocalizations can also be iconic and recognizable to people around the world—even when a speaker is not simply imitating a well-known sound. These findings, published in Scientific Reports, may help explain the rise of modern spoken language.

In 2015 language researchers challenged some English speakers to make up sounds representing various basic concepts (“sleep,” “child,” “meat,” “rock,” and more). When other English speakers listened to these sounds and tried matching them to concepts, they were largely successful. But “we wanted to be able to show that these vocalizations are understandable across cultures,” says study co-author and University of Birmingham cognitive scientist Marcus Perlman.

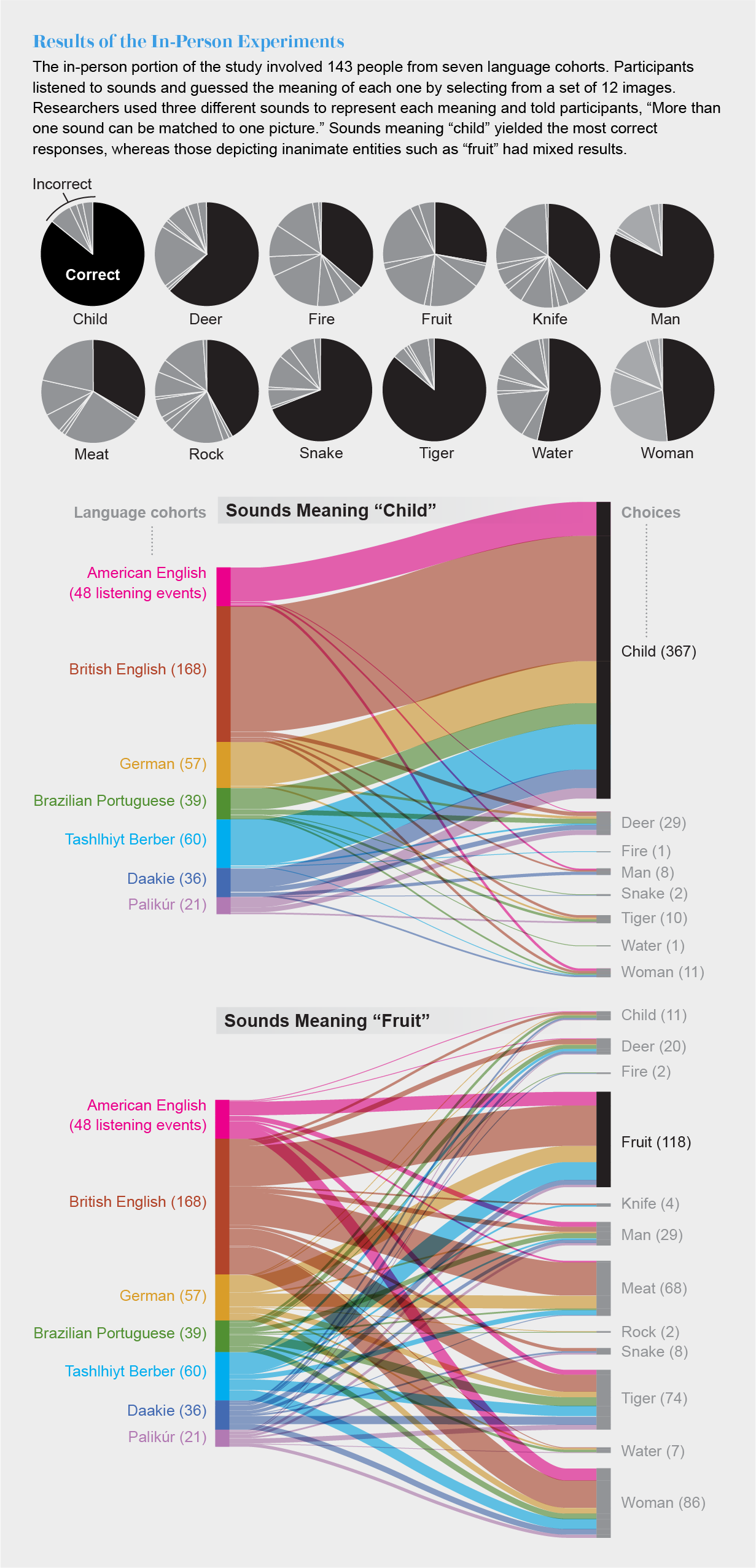

So Perlman and his colleagues conducted online and in-person experiments in seven countries, from Morocco to Brazil. They recruited more than 900 participants, who spoke a total of 28 languages, to listen to the best-understood vocalizations from the 2015 investigation and select matching concepts from a set of words or images. Vocalizations that evoked well-known sounds—for example, dripping water—performed best. But many others were also understood at rates significantly above chance across all languages tested, the team found. “There is a notable degree of success outside of just onomatopoeia,” Perlman says.

This is likely because certain acoustic patterns are universal, the team suggests. For example, short and basic sounds often convey the concept of “one,” and repeated sounds are typically associated with “many.” Likewise, low-pitched sounds accompany something big, and high-pitched sounds convey small size. These findings of “iconic” sounds could help scientists understand how human ancestors started using rich acoustic communication, says co-author Aleksandra Ćwiek, a linguist at the Leibniz-Center General Linguistics in Berlin. The human voice, she says, might “afford enough iconicity to get language off the ground.”

University of Tübingen linguist Matthias Urban, who was not involved in the research, agrees. “It’s unclear how words came into being in the first place,” he says. Iconic vocalizations are “potentially one pathway that could have been involved.”