Microplastics—minuscule, hard-to-degrade fragments of clothing fibers, water bottles and other synthetic items—have made their way into air, water and soil around the world.

Now new research published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces shows a way to promote their deterioration, at least in water, with technology on an even smaller scale: microrobots. When added to water along with a bit of hydrogen peroxide, the bacterium-sized devices glom onto microplastic particles and begin breaking them down.

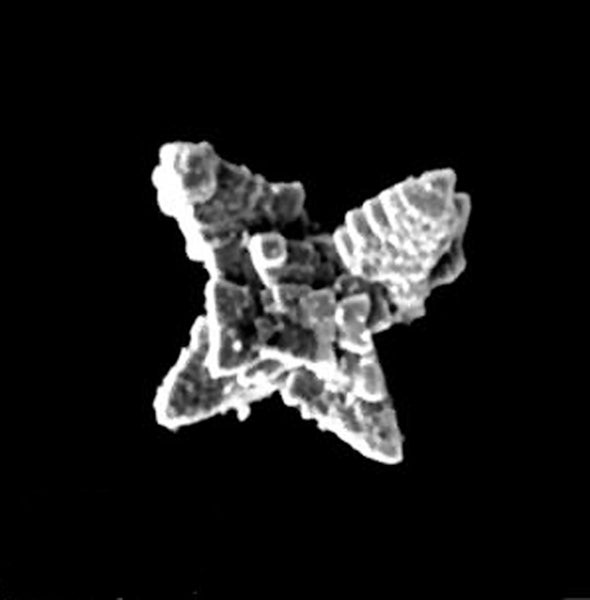

The metallic microrobots are shaped like four-pointed stars and coated with magnetic particles. Exposure to visible light causes electrons in the devices to absorb energy from and react with the surrounding water and hydrogen peroxide (a process called photocatalysis), making the bots move. “They can sweep a much larger area than you would be able to touch with stationary technology,” says study co-author Martin Pumera, a researcher at the University of Chemistry and Technology, Prague. As the microrobots adhere to plastic, photocatalysis also produces charged molecules. These break chemical bonds in the plastic's molecules, like a jeweler snipping bracelet links.

The researchers tested the microrobots on four types of plastic. After a week, all four had begun degrading, losing between 0.5 and 3 percent of their weight. In another test, the microrobots propelled themselves through a small channel and were collected by a magnet, bringing up to 70 percent of microplastic particles along for the ride.

Pumera envisions releasing future iterations of the bots into the sea to latch onto microplastics, then collecting the bots for reuse. But Win Cowger, who studies plastic pollution at the University of California, Riverside, and was not involved in the study, says any microrobots' potential usefulness is likely limited to closed systems such as those used to treat drinking water or wastewater.

Cowger notes that the current bots can also adhere to substances other than plastic and might not be safe if left in the water in large numbers. Pumera's team is now testing microrobots made from different materials that could address both concerns and could operate without hydrogen peroxide.

“The work is indeed highly interesting, but it needs further investigation to make this approach a really viable and potentially attractive technology to deal with the huge scale of microplastics,” University of Oxford chemists Peter Edwards and Sergio Gonzalez-Cortes wrote in an e-mail. The two researchers, who were not involved in the study, have proposed using microwave radiation to break down plastic waste.

For now, Cowger says, “the best way to remove microplastics from the environment is to stop them from getting there in the first place.”