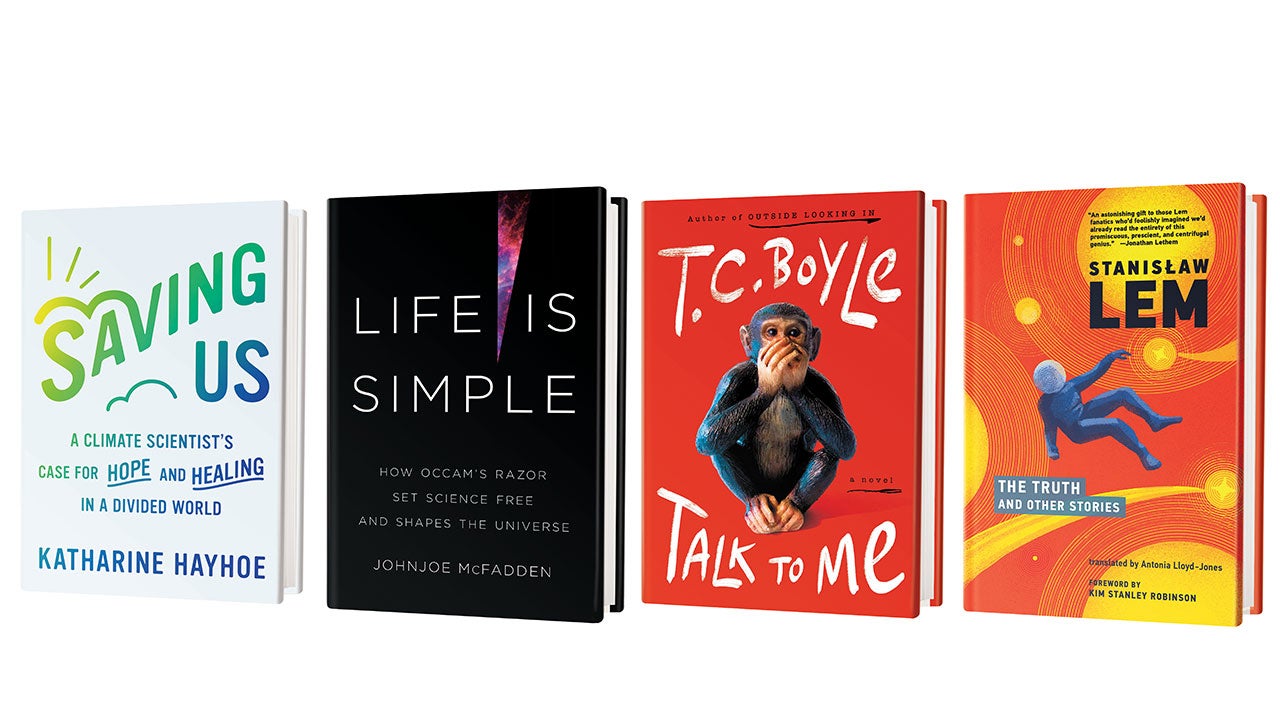

Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World

by Katharine Hayhoe

Atria/One Signal, 2021 ($27)

Once upon a time there was a world in mortal danger. Some people tried to stop it; others claimed it was ≈all a hoax. They squabbled on the Internet, calling one another terrible names, until they were swallowed up by the rising sea.

Once upon a time there was a polar bear. It died. And it was all your fault. You are to blame for the drought in California and the impending disintegration of the Greenland ice sheet.

Once upon a time there was a world, but who cares? It was doomed. Nothing could be done, and everyone was destined to be miserable.

I don’t like any of these stories, and I bet you don’t either. Much of the world’s failure to address climate change stems from a failure to tell different ones. I want to read climate science fiction that isn’t set in a dystopia. I want to see heist movies where charismatic teams pull off audacious robberies of fossil-fuel companies. I want time-traveling paleoclimate action scenes where the heroes fight Siberian volcanoes. I want personal narratives about anger crystallized into action and eulogies for the things we’re losing. I want a story that begins with scientists issuing desperate warnings, and then everybody listens and takes appropriate action, and it turns into a nice romantic comedy. If we’re going to save the planet from extreme weather and social chaos, we need more stories with heroes who make a better future possible.

As far as heroic characters go, I’m not sure you could do better than Katharine Hayhoe. She is an accomplished climate scientist and charismatic communicator as well as an evangelical Christian living in Lubbock, Tex. And she’s much nicer than most of us. This is evident on her social media feeds, where she tirelessly responds to bad-faith questions with grace. I don’t know how she summons the will to say for the umpteenth time that yes, it’s warming; no, it’s not a natural cycle; yes, it matters. But in doing so, she’s trying to make a point. The easiest climate solution, she says, is to talk about it. Not necessarily to the “dismissives,” the small but loud minority who are convinced it’s all a hoax, but to their audiences, the lurkers who read but don’t engage. Hayhoe knows that on the Internet, someone is always watching.

In Hayhoe’s excellent new book, Saving Us, she argues that everyone can take a role in this performance. After a deliberately perfunctory summary of the facts (it’s real; it’s us), she gets right to the point: they’re not enough. We’re swimming in more facts than any human brain can process. We’re prone to information overload and motivated reasoning, especially when something threatens our identity, feelings or sense of morality. What if, Hayhoe suggests, we talked about that?

The central argument of Hayhoe’s book is that we can counter bad narratives with better ones. For instance: Is climate change an abstract concept? No, it is already strengthening hurricanes, causing droughts and amplifying heat waves. Is the cure worse than the disease? No, climate solutions have massive health benefits. Can we afford climate action? We can’t afford the effects of climate change. For more productive conversations, Hayhoe suggests focusing on shared values. Her stories go something like this: Once upon a time, a climate scientist gave a talk to a hostile audience. They were prepared to tune her out or shout her down. But she spoke their language, cared about the things they loved and understood their fears. So they listened. And that, for her, was a good start.

Saving Us also confronts some of the most unhelpful climate stories. Hayhoe has no patience for public shaming and purity tests. She admirably debunks the myth that we’re doomed. I’ve always thought that people who say climate action is impossible because of “human nature” don’t understand humans or nature. I agree with Hayhoe that not only is a better future physically possible, but we have most of the tools we need to bring it about.

That’s not to say the book is perfect. Hayhoe can seem too credulous at times. I found it hard to believe that an oil-drilling executive might change his career trajectory after one of her talks, and I’m wary of accepting the climate commitments of fossil-fuel companies at face value. Climate action is pro-life, she says, and I agree completely. But a cynic might suggest that branding other objectively pro-life policies (gun control, humanitarian aid, death-penalty abolition) as such has not increased their traction in conservative circles. Climate action requires not just narrative but amassing and exercising raw political power. Many wealthy people stand to lose influence and easy money when the rest of the planet gains. They have vested interests in stopping climate action. And they know how to talk, too.

Can the voices of millions counter the megaphones of the rich? Is the power of empathy, character and storytelling enough to overcome the power of, well, power? Hayhoe thinks so—at least she is convinced that good stories can change the world. It can be tempting to read her book and think: What planet is Katharine Hayhoe living on? The answer, of course, is one in which greenhouse gas emissions do not continue their unabated rise, where we can limit global warming to avoid the worst-case scenarios. We may not all live on the same planet as Katharine Hayhoe, but I hope we can get there soon.

Because whatever our world looks like right now, the science says it’s rapidly becoming something else. That means another story is possible, and it goes something like this: Once upon a time, there was a world full of wondrous creatures who built roads and cities, canals and fields. All of this was powered by cheap energy that they dug out of the ground. When they learned how that energy was poisoning the world, they embraced their agency rather than denying their impact on the planet. Everyone played their part to restore balance: some harvested the wind and sun, some worked to draw the poison out, some demanded their leaders take things seriously. They rebuilt it all, grieving what they lost and saving what they could. —Kate Marvel

Life Is Simple: How Occam’s Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe

by Johnjoe McFadden

Basic Books, 2021 ($32)

Named for 14th-century philosopher William of Ockham, Occam’s razor is the scientific principle that “entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity.” In Life Is Simple, geneticist Johnjoe McFadden offers a breezy but well-researched look at how the razor has inspired some of science’s biggest ideas, from Copernicus’s view of the universe to the Standard Model of particle physics. Taken together, his examples illustrate with persuasive power how “simplicity continues to present us with the most profound, enigmatic and sometimes unsettling insights” into how the universe works. —Amy Brady

Talk to Me

by T. C. Boyle

Ecco, 2021 ($27.99)

In T. C. Boyle’s latest novel, clearly inspired by the infamous Nim Chimpsky experiment—an attempt to prove, contra Chomsky, that humans weren’t the only animals able to acquire language—fictional animal behaviorist Guy Schermerhorn is raising a Chimpskyesque ape named Sam in a house outside his California college town, teaching him to “speak” American Sign Language. Schermerhorn wants to “lift the roof right off of everything we’ve ever known about animal consciousness”; he also wants to go on Johnny Carson. What starts as a comedy about an interspecies love triangle quickly moves into darker territory. The book’s real subject is human selfishness and cruelty, particularly as practiced by the male of the species. —Seth Fletcher

The Truth and Other Stories

by Stanisław Lem, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

MIT Press, 2021 ($39.95)

This collection by the late Polish writer Stanislaw Lem is made up of mostly mid-20th-century stories that have been translated and published in English for the first time. Lem’s protagonists embody both “inflamed curiosity” and resigned unease as they encounter the runaway consequences of new technologies. Sci-fi writer Kim Stanley Robinson, who wrote the foreword, calls Lem’s voice “passionately rational.” Novelist and critic John Updike once described Lem’s writing as engaging, “especially for those whose hearts beat faster when the Scientific American arrives each month.” Indeed, as our world changes faster than we can make sense of it, Lem’s prescient imagination shows the power of science fiction for peering into the future. —Jen Schwartz