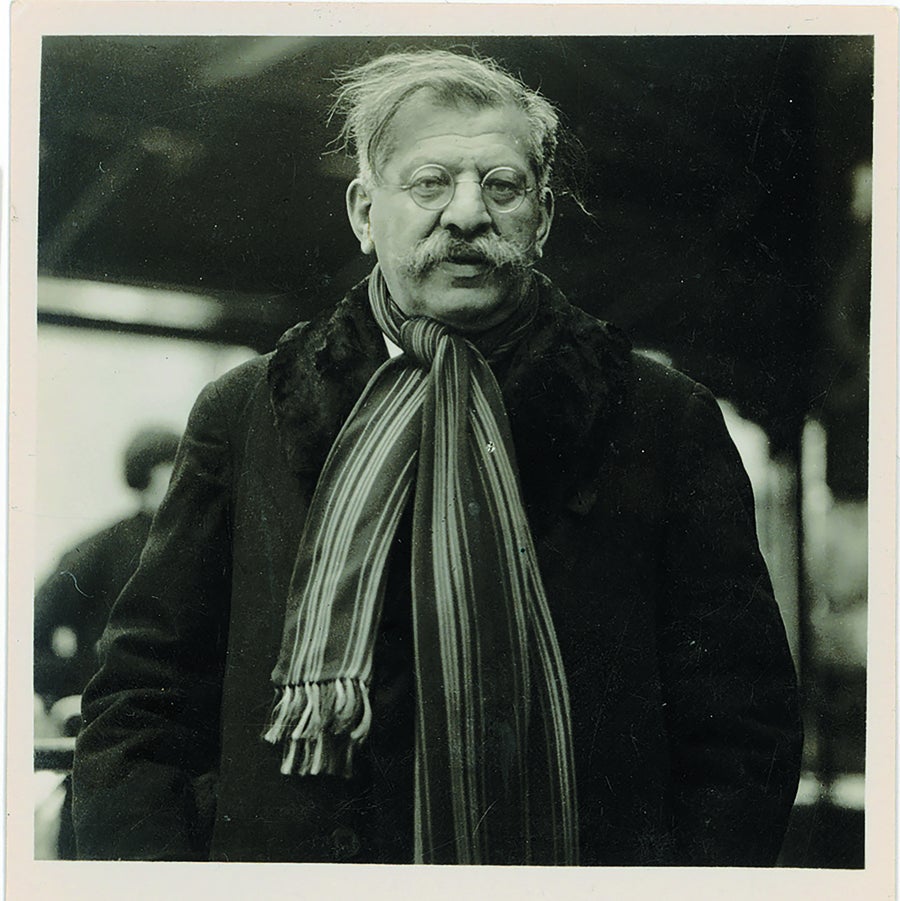

Late one night on the cusp of the 20th century, Magnus Hirschfeld, a young doctor, found a soldier on the doorstep of his practice in Germany. Distraught and agitated, the man had come to confess himself an Urning—a word used to refer to homosexual men. It explained the cover of darkness; to speak of such things was dangerous business. The infamous “Paragraph 175” in the German criminal code made homosexuality illegal; a man so accused could be stripped of his ranks and titles and thrown in jail.

Hirschfeld understood the soldier’s plight—he was himself both homosexual and Jewish—and did his best to comfort his patient. But the soldier had already made up his mind. It was the eve of his wedding, an event he could not face. Shortly after, he shot himself.

The soldier bequeathed his private papers to Hirschfeld, along with a letter: “The thought that you could contribute to [a future] when the German fatherland will think of us in more just terms,” he wrote, “sweetens the hour of death.” Hirschfeld would be forever haunted by this needless loss; the soldier had called himself a “curse,” fit only to die, because the expectations of heterosexual norms, reinforced by marriage and law, made no room for his kind. These heartbreaking stories, Hirschfeld wrote in The Sexual History of the World War, “bring before us the whole tragedy [in Germany]; what fatherland did they have, and for what freedom were they fighting?” In the aftermath of this lonely death, Hirschfeld left his medical practice and began a crusade for justice that would alter the course of queer history.

Hirschfeld sought to specialize in sexual health, an area of growing interest. Many of his predecessors and colleagues believed that homosexuality was pathological, using new theories from psychology to suggest it was a sign of mental ill health. Hirschfeld, in contrast, argued that a person may be born with characteristics that did not fit into heterosexual or binary categories and supported the idea that a “third sex” (or Geschlecht) existed naturally. Hirschfeld proposed the term “sexual intermediaries” for nonconforming individuals. Included under this umbrella were what he considered “situational” and “constitutional” homosexuals—a recognition that there is often a spectrum of bisexual practice—as well as what he termed “transvestites.” This group included those who wished to wear the clothes of the opposite sex and those who “from the point of view of their character” should be considered as the opposite sex. One soldier with whom Hirschfeld had worked described wearing women’s clothing as the chance “to be a human being at least for a moment.” He likewise recognized that these people could be either homosexual or heterosexual, something that is frequently misunderstood about transgender people today.

Perhaps even more surprising was Hirschfeld’s inclusion of those with no fixed gender, akin to today’s concept of gender-fluid or nonbinary identity (he counted French novelist George Sand among them). Most important for Hirschfeld, these people were acting “in accordance with their nature,” not against it.

If this seems like extremely forward thinking for the time, it was. It was possibly even more forward than our own thinking, 100 years later. Current anti-trans sentiments center on the idea that being transgender is both new and unnatural. In the wake of a U.K. court decision in 2020 limiting trans rights, an editorial in the Economist argued that other countries should follow suit, and an editorial in the Observer praised the court for resisting a “disturbing trend” of children receiving gender-affirming health care as part of a transition.

Related: The Disturbing History of Research into Transgender Identity

But history bears witness to the plurality of gender and sexuality. Hirschfeld considered Socrates, Michelangelo and Shakespeare to be sexual intermediaries; he considered himself and his partner Karl Giese to be the same. Hirschfeld’s own predecessor in sexology, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, had claimed in the 19th century that homosexuality was natural sexual variation and congenital.

Hirschfeld’s study of sexual intermediaries was no trend or fad; instead it was a recognition that people may be born with a nature contrary to their assigned gender. And in cases where the desire to live as the opposite sex was strong, he thought science ought to provide a means of transition. He purchased a Berlin villa in early 1919 and opened the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (the Institute for Sexual Research) on July 6. By 1930 it would perform the first modern gender-affirmation surgeries in the world.

A Place of Safety

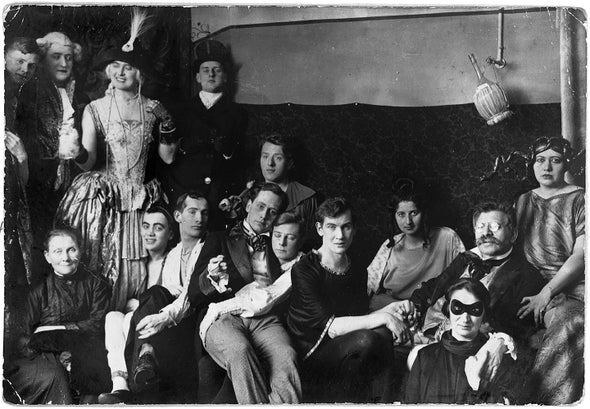

A corner building with wings to either side, the institute was an architectural gem that blurred the line between professional and intimate living spaces. A journalist reported it could not be a scientific institute, because it was furnished, plush and “full of life everywhere.” Its stated purpose was to be a place of “research, teaching, healing, and refuge” that could “free the individual from physical ailments, psychological afflictions, and social deprivation.” Hirschfeld’s institute would also be a place of education. While in medical school, he had experienced the trauma of watching as a gay man was paraded naked before the class, to be verbally abused as a degenerate.

Hirschfeld would instead provide sex education and health clinics, advice on contraception, and research on gender and sexuality, both anthropological and psychological. He worked tirelessly to try to overturn Paragraph 175. Unable to do so, he got legally accepted “transvestite” identity cards for his patients, intended to prevent them from being arrested for openly dressing and living as the opposite sex. The grounds also included room for offices given over to feminist activists, as well as a printing house for sex reform journals meant to dispel myths about sexuality. “Love,” Hirschfeld said, “is as varied as people are.”

The institute would ultimately house an immense library on sexuality, gathered over many years and including rare books and diagrams and protocols for male-to-female (MTF) surgical transition. In addition to psychiatrists for therapy, he had hired Ludwig Levy-Lenz, a gynecologist. Together, with surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt, they performed male-to-female surgery called Genitalumwandlung—literally, “transformation of genitals.” This occurred in stages: castration, penectomy and vaginoplasty. (The institute treated only trans women at this time; female-to-male phalloplasty would not be practiced until the late 1940s.) Patients would also be prescribed hormone therapy, allowing them to grow natural breasts and softer features.

Their groundbreaking studies, meticulously documented, drew international attention. Legal rights and recognition did not immediately follow, however. After surgery, some trans women had difficulty getting work to support themselves, and as a result, five were employed at the institute itself. In this way, Hirschfeld sought to provide a safe space for those whose altered bodies differed from the gender they were assigned at birth—including, at times, protection from the law.

Lives Worth Living

That such an institute existed as early as 1919, recognizing the plurality of gender identity and offering support, comes as a surprise to many. It should have been the bedrock on which to build a bolder future. But as the institute celebrated its first decade, the Nazi party was already on the rise. By 1932 it was the largest political party in Germany, growing its numbers through a nationalism that targeted the immigrant, the disabled and the “genetically unfit.” Weakened by economic crisis and without a majority, the Weimar Republic collapsed.

Adolf Hitler was named chancellor on January 30, 1933, and enacted policies to rid Germany of Lebensunwertes Leben, or “lives unworthy of living.” What began as a sterilization program ultimately led to the extermination of millions of Jews, Roma, Soviet and Polish citizens—and homosexuals and transgender people.

When the Nazis came for the institute on May 6, 1933, Hirschfeld was out of the country. Giese fled with what little he could. Troops swarmed the building, carrying off a bronze bust of Hirschfeld and all his precious books, which they piled in the street. Soon a towerlike bonfire engulfed more than 20,000 books, some of them rare copies that had helped provide a historiography for nonconforming people.

The carnage flickered over German newsreels. It was among the first and largest of the Nazi book burnings. Nazi youth, students and soldiers participated in the destruction, while voiceovers of the footage declared that the German state had committed “the intellectual garbage of the past” to the flames. The collection was irreplaceable.

Levy-Lenz, who like Hirschfeld was Jewish, fled Germany. But in a dark twist, his collaborator Gohrbandt, with whom he had performed supportive operations, joined the Luftwaffe as chief medical adviser and later contributed to grim experiments in the Dachau concentration camp. Hirschfeld’s likeness would be reproduced on Nazi propaganda as the worst kind of offender (both Jewish and homosexual) to the perfect heteronormative Aryan race.

In the immediate aftermath of the Nazi raid, Giese joined Hirschfeld and his protégé Li Shiu Tong, a medical student, in Paris. The three would continue living together as partners and colleagues with hopes of rebuilding the institute, until the growing threat of Nazi occupation in Paris required them to flee to Nice. Hirschfeld died of a sudden stroke in 1935 while still on the run. Giese died by suicide in 1938. Tong abandoned his hopes of opening an institute in Hong Kong for a life of obscurity abroad.

Over time their stories have resurfaced in popular culture. In 2015, for instance, the institute was a major plot point in the second season of the television show Transparent, and one of Hirschfeld’s patients, Lili Elbe, was the protagonist of the film The Danish Girl. Notably, the doctor’s name never appears in the novel that inspired the movie, and despite these few exceptions the history of Hirschfeld’s clinic has been effectively erased. So effectively, in fact, that although the Nazi newsreels still exist, and the pictures of the burning library are often reproduced, few know they feature the world’s first trans clinic. Even that iconic image has been decontextualized, a nameless tragedy.

The Nazi ideal had been based on white, cishet (that is, cisgender and heterosexual) masculinity masquerading as genetic superiority. Any who strayed were considered as depraved, immoral, and worthy of total eradication. What began as a project of “protecting” German youth and raising healthy families had become, under Hitler, a mechanism for genocide.

A Note for the Future

The future doesn’t always guarantee progress, even as time moves forward, and the story of the Institute for Sexual Research sounds a warning for our present moment. Current legislation and indeed calls even to separate trans children from supportive parents bear a striking resemblance to those terrible campaigns against so-labeled aberrant lives.

Studies have shown that supportive hormone therapy, accessed at an early age, lowers rates of suicide among trans youth. But there are those who reject the evidence that trans identity is something you can be “born with.” Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins was recently stripped of his “humanist of the year” award for comments comparing trans people to Rachel Dolezal, a civil rights activist who posed as a Black woman, as though gender transition were a kind of duplicity. His comments come on the heels of legislation in Florida aiming to ban trans athletes from participating in sports and an Arkansas bill denying trans children and teens supportive care.

Looking back on the story of Hirschfeld’s institute—his protocols not only for surgery but for a trans-supportive community of care, for mental and physical healing, and for social change—it’s hard not to imagine a history that might have been. What future might have been built from a platform where “sexual intermediaries” were indeed thought of in “more just terms”? Still, these pioneers and their heroic sacrifices help to deepen a sense of pride—and of legacy—for LGBTQ+ communities worldwide. As we confront oppressive legislation today, may we find hope in the history of the institute and a cautionary tale in the Nazis who were bent on erasing it.