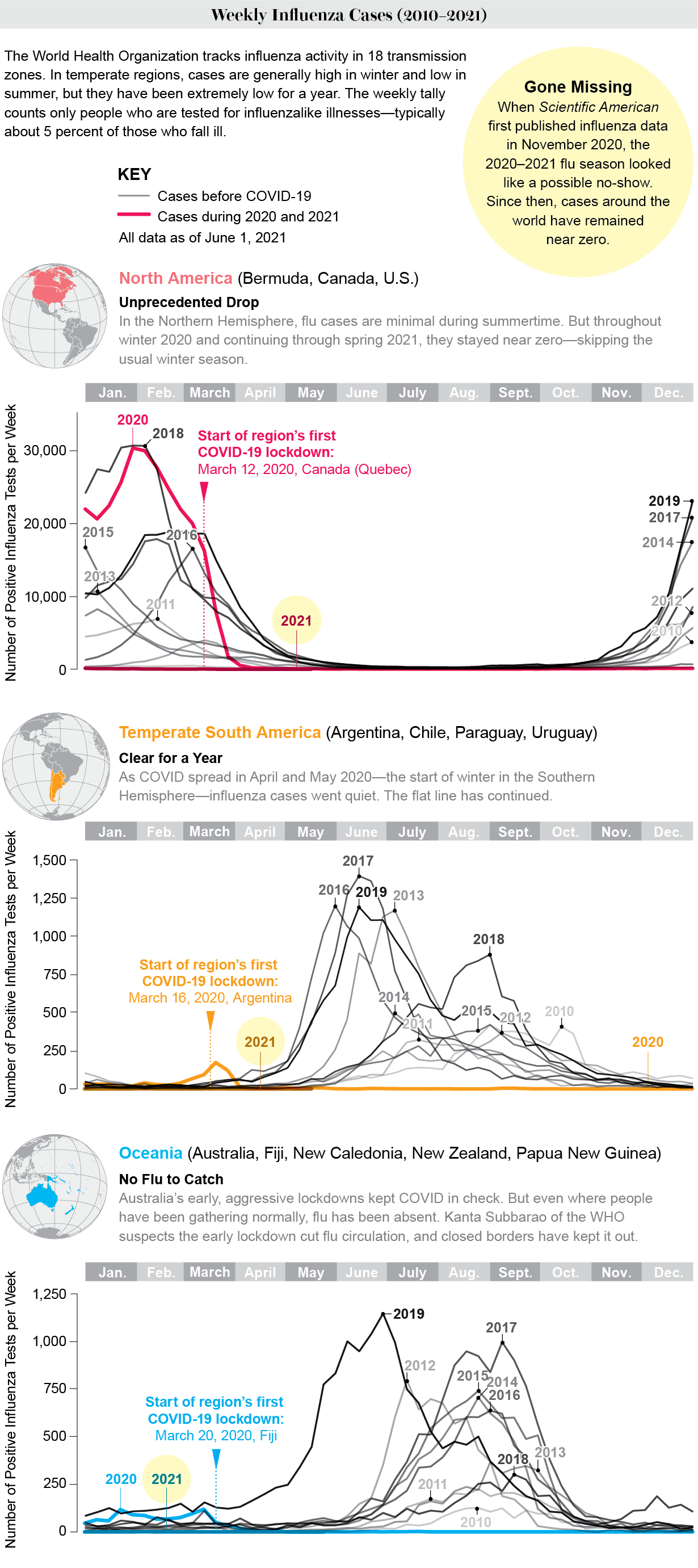

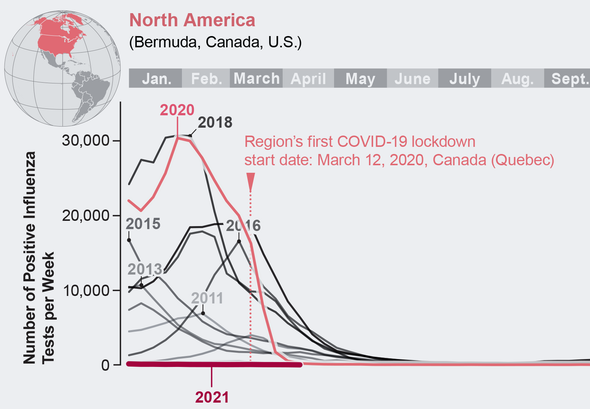

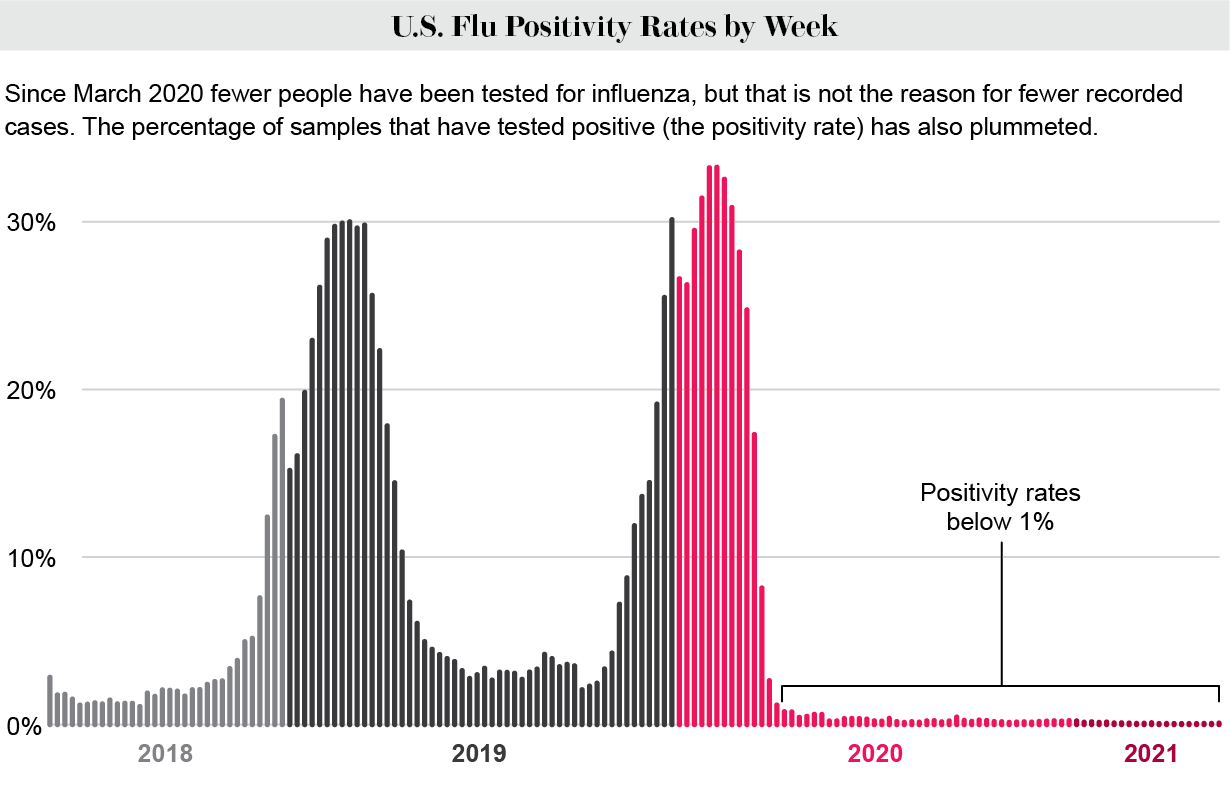

Since the novel coronavirus began its global spread, influenza cases reported to the World Health Organization from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres have dropped to minute levels. The reason, epidemiologists think, is that the public health measures taken to keep the coronavirus from spreading—notably mask wearing and social distancing—also stop the flu. Influenza viruses are transmitted in much the same way as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and they are less effective at jumping from person to person.

As Scientific American reported in November 2020, the drop-off in flu numbers following COVID’s arrival was swift and global. Since then, cases have stayed remarkably low. “There’s just no flu circulating,” says Greg Poland, who has studied the disease at the Mayo Clinic for decades. The U.S. saw about 700 deaths from influenza during the 2020–2021 season. In comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates there were approximately 22,000 U.S. deaths in the prior season and 34,000 deaths two seasons ago.

Because each year’s flu vaccine is based on strains that have been circulating around the world during the past 12 months, it is unclear how the upcoming 2021–2022 vaccine will fare should the typical patterns of infection return. The WHO made its flu strain recommendations in late February as usual, but they were based on far fewer cases than normal. Yet with less virus circulating, there is a reduced chance of mutation, so the upcoming vaccine could be especially effective.

Public health experts are grateful for the reprieve in cases. If the future includes more hand washing, face covering and temporary social distancing when people become sick, perhaps flu seasons can be less severe, even as health restrictions lift and groups gather together again.