Over the past year, the successful development of highly effective vaccines to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection has moved forward at a rapid pace—but the use of treatments for patients sickened by the virus has lagged. A number of barriers have stood in the way of using the drugs known as monoclonal antibodies, including logistical challenges and the emergence of new viral variants that are resistant to some of these antibodies. Although they are not a cure for COVID, monoclonals can serve as an effective therapeutic option that can prevent a patient with mild or moderate disease from becoming sicker and ending up in the hospital.

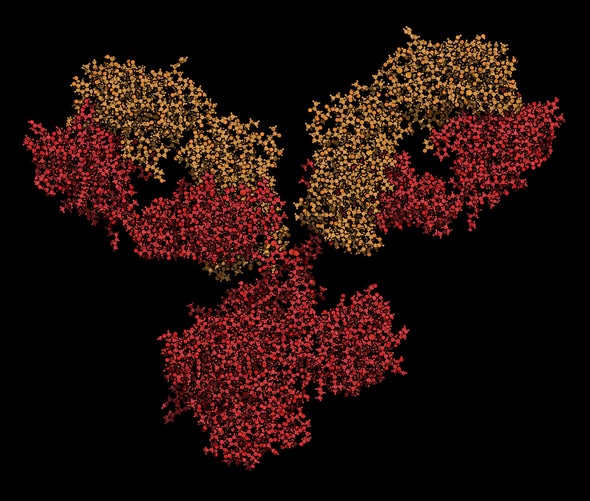

Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-made molecules that in this case mimic the immune system response to SARS-CoV-2, targeting a specific portion of the protruding “spike” proteins on the surface of the virus, preventing it from binding to cells or tagging it for destruction. Researchers first isolate antibody-producing B cells from patients who have recovered from COVID. They go on to find the most potent of these antibodies and then produce them in mice engineered with components of the human immune system.

The use of monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of COVID gained national and international attention last October, when President Trump received an antibody cocktail made by Regeneron after he was diagnosed with the illness. Shortly thereafter, two monoclonal compounds received Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the U.S. FDA and were expected to be a key part of the response to the pandemic.

But a number of factors have limited their use. There has been a rise in more contagious SARS-CoV-2 variants, some of which exhibit decreased susceptibility to the monoclonal antibodies. Difficulties have also arisen in administering these compounds to outpatients with mild and moderate disease in overwhelmed hospitals. Nonetheless, the use of these drugs can still slow disease in some patients who are at risk of worsening, and they may also be useful in prevention.

Today there are several monoclonal antibodies that have been studied and for which the FDA has given EUA. This designation is not a formal approval, but it lets drugs be used during public health crises. Drugs with EUAs initially included bamlanivimab (also known as LY-CoV555 and LY3819253), etesevimab (LY-CoV016 and LY3832479), casirivimab (previously REGN10933) and imdevimab (previously REGN10987). In November, the FDA granted an EUA for both bamlanivimab and, separately, the combination of casirivimab/imdevimab for use in outpatients with mild to moderate COVID who are at high risk of progression to severe illness.

These approvals were based on an interim analysis of two mid-stage (phase II) clinical studies among outpatients with mild to moderate COVID in which these compounds appeared to accelerate the decline in viral load in a patient. However, because of an increase in the number of SARS-CoV-2 variants resistant to bamlanivimab (from approximately 5 percent in mid-January to 20 percent in mid-March 2021), the FDA revoked the EUA for bamlanivimab on April 16, 2021, and it is no longer available for use as a sole treatment for patients. Nevertheless, two products that combine monoclonals (bamlanivimab plus etesevimab, or casirivimab plus imdevimab), are still available through an EUA for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID in nonhospitalized patients at high risk of progressing to severe disease or hospitalization. None of these drugs have been shown to be of benefit in sicker hospitalized patients.

Currently the NIH COVID treatment guidelines recommend that one of the two cocktails be administered for the treatment of outpatients diagnosed with mild to moderate COVID infection who are at high risk of progression to severe disease. The treatment criteria include having a body mass index of 35 or more, being 65 or older, having diabetes, chronic kidney disease or an immunosuppressive disease, or taking an immunosuppressive drug. Some people younger than 65 are also eligible if they meet specific requirements. Data on the use of these drugs for patients younger than 18 years old are limited.

When prescribing these therapies, it is important that treatment be started as soon as possible after the diagnosis and within 10 days of onset of symptoms. The Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines note that the data are stronger for bamlanivimab/etesevimab than for casirivimab/imdevimab. However, they also recommend that prescribers take into account which variants are circulating in the community and whether or not they are susceptible to monoclonal treatments.

The rollout for monoclonals came only slightly before the introduction of highly effective vaccines. With the vaccines’ arrival, monoclonals have not been as widely used as originally contemplated and are being reserved for people who cannot be vaccinated, those who do not respond to the vaccine or people who need immediate prophylaxis after a significant exposure.

After President Trump was treated with monoclonals and after the FDA issued its EUA, the federal government purchased over 500,000 doses of both bamlamivimab and casirivimav/imdevimab, expecting high demand for these drugs.

Not only was the demand from patients weaker than projected but hospitals and clinics struggled to get these treatments to patients. There are several explanations as to why. Patients sometimes delay seeking care until more than 10 days after the onset of symptoms. Test results may lag. Logistical issues emerge in administering an infusion or injection at a site where a patient with COVID can be safely seen. Probably the largest barrier over the December-to-January period was that hospitals were overwhelmed with sick patients and simply lacked the staff to administer these drugs to patients that were “not sick enough.”

So, do I still think these are useful drugs? Absolutely. We are currently recording around 60,000 new infections per day in the U.S., and many are occurring among persons who would benefit from monoclonal antibody therapy to prevent progression of COVID to severe disease and hospitalization. The word about monoclonals still needs to get out. Regeneron, in fact, aired an advertisement during the 2021 Academy Awards, hoping to educate patients about the value of these compounds.

For monoclonals to be more widely distributed, the possibility of administering them subcutaneously or intramuscularly rather than intravenously should be explored. We should also move their administration from the clinic into pharmacies and testing sites where it can be more easily and readily done.

As long as we continue to have cases of COVID, vaccination should not be the only strategy we implement for control. While progress has been made vaccinating high-risk populations in the U.S., we still need to increase access to effective therapies that can prevent disease progression, hospitalization and death among those who get infected with SARS-CoV-2.

This is an opinion and analysis article.