When adults claim to have suddenly recalled painful events from their childhood, are those memories likely to be accurate? This question is the basis of the “memory wars” that have roiled psychology for decades. And the validity of buried trauma turns up as a point of contention in court cases and in television and movie story lines.

Warnings about the reliability of a forgotten traumatic event that is later recalled—known formally as a delayed memory—have been endorsed by leading mental health organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The skepticism is based on a body of research showing that memory is unreliable and that simple manipulations in the lab can make people believe they had an experience that never happened. Some prominent cases of recovered memory of child abuse have turned out to be false, elicited by overzealous therapists.

But psychotherapists who specialize in treating adult survivors of childhood trauma argue that laboratory experiments do not rule out the possibility that some delayed memories recalled by adults are factual. Trauma therapists assert that abuse experienced early in life can overwhelm the central nervous system, causing children to split off a painful memory from conscious awareness. They maintain that this psychological defense mechanism—known as dissociative amnesia—turns up routinely in the patients they encounter.

Tensions between the two positions have often been framed as a debate between hard-core scientists on the false-memory side and therapists in clinical practice in the delayed-memory camp. But clinicians who also do research have been publishing peer-reviewed studies of dissociative amnesia in leading journals for decades. A study published in February in the American Journal of Psychiatry, the flagship journal of the APA, highlights the considerable scientific evidence that bolsters the arguments of trauma therapists.

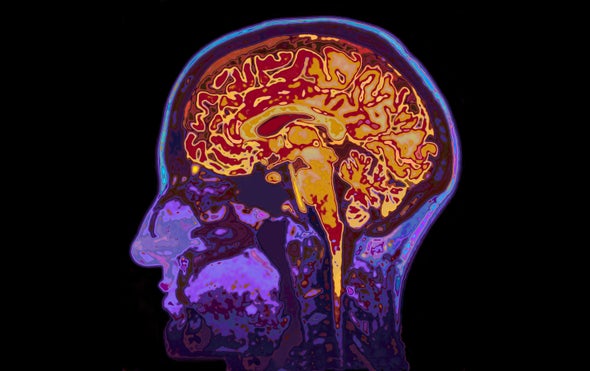

The new paper uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study amnesia, along with various other dissociative experiences that are often said to occur in the wake of severe child abuse, such as feelings of unreality and depersonalization. In an editorial published in the same issue of the journal, Vinod Menon, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, praised the researchers for “[uncovering] a potential brain circuit mechanism underlying individual differences in dissociative symptoms in adults with early-life trauma and PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder].”

Milissa Kaufman is senior author of the new MRI study and head of the dissociative disorders and trauma research program at McLean Hospital, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard Medical School. She notes that, as with earlier MRI studies of trauma survivors, this one shows that there is a neurological basis for dissociative symptoms such as amnesia. “We think that these brain studies can help reduce the stigma associated with our work,” Kaufman says. “Like many therapists who treat adult survivors of severe child abuse, I have seen some patients who recover memories of abuse.”

Since 1980, dissociative amnesia has been listed as a common symptom of PSTD in every edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—psychiatry’s diagnostic bible. The condition has been backed up not just by psychiatric case studies but by dozens of studies involving victims of child abuse, natural disaster, torture, rape, kidnapping, wartime violence and other trauma.

For example, two decades ago psychiatrist James Chu, then director of the trauma and dissociative disorders program at McLean Hospital, published a study involving dozens of women receiving in-patient treatment who had experienced childhood abuse. A majority of the women reported previously having partial or complete amnesia of these events, which they typically remembered not in a therapy session but while at home alone or with family or friends. In many instances, Chu wrote, these women “were able to find strong corroboration of their recovered memories.”

False-memory proponents have warned that the use of leading questions by investigators might seed an untrue recollection. As psychiatrist Michael I. Goode wrote of Chu’s study in a letter to the editor, “Participants were asked ‘if there was a period during which they “did not remember that this [traumatic] experience happened.”’ With this question alone, the actuality of the traumatic experience was inherently validated by the investigators.”

MRI studies conducted over the past two decades have found that PTSD patients with dissociative amnesia exhibit reduced activity in the amygdala—a brain region that controls the processing of emotion—and increased activity in the prefrontal cortex, which controls planning, focus and other executive functioning skills. In contrast, PTSD patients who report no lapse in their memories of trauma exhibit increased activity in the amygdala and reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex.

“The reason for these differences in neuronal circuitry is that PTSD patients with dissociative symptoms such as amnesia and depersonalization—a group comprising somewhere between 15 and 30 percent of all PTSD patients—shut down emotionally in response to trauma,” says Ruth Lanius, a professor of psychiatry and director of the PTSD research unit at the University of Western Ontario, who has conducted several of these MRI studies. Children may try to detach from abuse to avoid intolerable emotional pain, which can result in forgetting an experience for many years, she maintains. “Dissociation involves a psychological escape when a physical escape is not possible,” Lanius adds.

False-memory researchers remain skeptical of the brain-imaging studies. Henry Otgaar, a professor of legal psychology at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, who has co-authored more than 100 academic publications on false-memory research and who often serves as an expert witness for defendants in abuse cases, maintains that intact autobiographical memories are rarely—if ever—repressed. “These brain studies provide biological evidence just for the claims of patients who report memory loss due to dissociation,” he says. “There are many alternative explanations for these correlations—say, retrograde amnesia, in which the forgetting is due to a brain injury.”

In an effort to provide a firmer grounding for their arguments, Kaufman and her McLean colleagues used artificial intelligence to develop a model of the connections between diverse brain networks that could account for dissociative symptoms. They fed the computer MRI data on 65 women with histories of childhood abuse who had been diagnosed with PTSD, along with their scores on a commonly used inventory of dissociative symptoms. “The computer did the rest,” Kaufman says.

Her key finding is that severe dissociative symptoms likely involve the connections between two specific brain networks that are active at the same time: the so-called default mode network—which kicks in when the mind is at rest and involves remembering the past and envisioning the future—and the frontoparietal control network—which is involved in problem-solving.

The McLean study is not the first attempt to apply machine learning to dissociative symptoms. In a paper published in the September 2019 issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry, researchers showed how MRI scans of the brain structures of 75 women—32 with dissociative identity disorder, for which dissociative amnesia is a key symptom, and 43 matched controls—could discriminate between people with or without the disorder nearly 75 percent of the time.

Kaufman says additional research needs to be carried out before clinicians can begin using brain connectivity as a diagnostic tool to assess the severity of dissociative symptoms in their patients. “This study is just a first step on the pathway to precision medicine in our field,” she says.

Richard Friedman, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, considers the goal of the McLean researchers laudable. But he notes that the road ahead remains challenging and warns that the history of psychology is filled with “objective assessments” for a particular diagnosis or state of mind that never lived up to their hype. Friedman cites the case of lie-detector tests, in which false positives and false negatives abound.

While a brain-based test that could diagnose dissociative symptoms is not likely anytime soon, research on neurobiological explanations show the controversy over forgetting and remembering traumatic memories is far from settled.