On an overcast late April day in Newark, N.J., after more than a year of pandemic suffering, some 2,000 people queued up at a public college campus to start healing. Inside a hangar-style tennis facility at the New Jersey Institute of Technology that had been converted into a mass vaccination site, they came face to face with one of the most remarkable biomedical achievements in history: a safe and highly effective COVID vaccine designed and tested in a 10-month sprint in 2020. During that same period, while scientists were racing to develop this virus blocker, more than 300,000 Americans and nearly two million people worldwide died of COVID.

Although the two-dose vaccine made by Pfizer-BioNTech and given in Newark was configured rapidly for the SARS-CoV-2 virus—along with a similar inoculation from biotech firm Moderna—both are the careful culmination of decades of research into technology known as synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA). The shots gave the world its first real sign that humanity could break free of the pandemic.

Research into vaccines made from mRNA, conducted at the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense and several academic laboratories, yielded a way to use this compound to get the body’s own cells to make a viral protein that provokes a strong immune response. Two different clinical trials, involving more than 70,000 people, were reviewed by vaccine and safety experts at the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as outside advisory panels; the tests showed that the shots are healthy and extremely effective and led to vaccine authorization.

But the shots have not reached everyone equally. In the U.S., social and material barriers confront many people of color, including lack of transportation to clinics and computer access for making appointments and no paid time off, and the obstacles have meant that white people receive a disproportionate share of vaccine doses. The Newark site was created to address this problem. It is a joint state and federal effort that is managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Defense. The site is located near train stations and bus stops. People who show up without appointments get booked for an upcoming date or even accommodated that day if supplies allow. Messages and instructions are available for visitors more comfortable in one of more than 50 languages, and some staffers are fluent in Portuguese, Spanish, and more. A video is available for people who communicate in American Sign Language. On April 30, a month after it opened, the site vaccinated its 150,000th person.

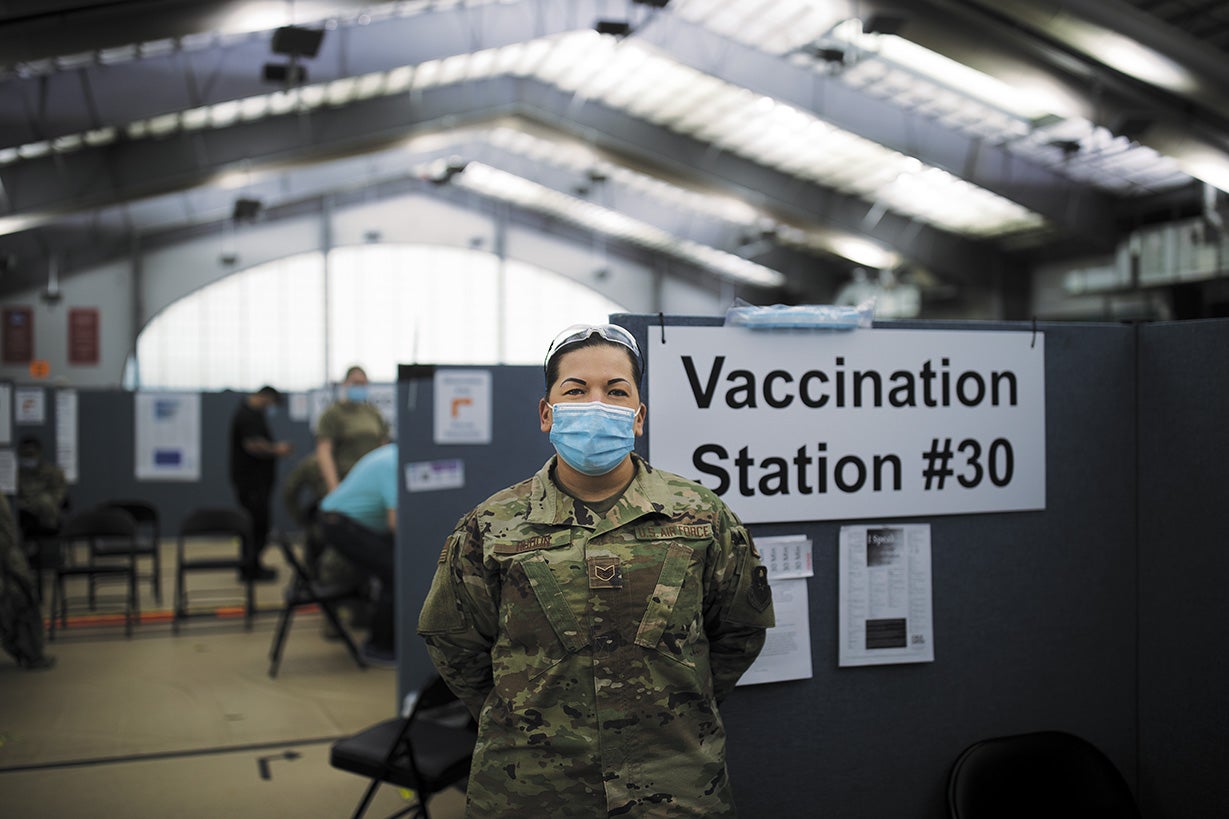

People arriving at the facility moved between rows of folding tables. After registering at one of 36 intake stations with Plexiglas barriers between patients and seated workers, patients walked down an improvised corridor toward one of 50 vaccination stations staffed by members of the military in fatigues. Tall partitions covered in steel-blue fabric maintained a sense of privacy. A military medic explained the two-dose regimen for the vaccine and the protection it provides, then asked if patients had any concerns.

These sites cannot reverse the huge missteps of the pandemic’s first year or fix the web of health disadvantages spun by structural inequalities. And what has been done in the wealthy U.S. is still beyond the reach of much of the planet; large areas continue to suffer. But these photographs, taken on April 20, show encounters between people and the vaccines that can save them after a tragic year. They reveal the human side of the progress that is possible when societies use science—and compassion—to tackle the biggest problems.

Carmita Andrade, 51 (center), thought she might die when she had COVID last year in April. She could hardly breathe. Her trauma, which included a week-long hospitalization, helped to inspire her son, Christopher, and her daughter, Nicole, to join her in getting vaccinated this spring. “I’m a survivor here,” she says. “My biggest concern was to go to the hospital because you didn’t know if you were coming back again. A lot of people who passed away because of COVID, they couldn’t say goodbye to their families. But I’ve been very blessed to be back again with my family.”

Alex Appiah Frimpong, 50, a former life insurance agent who is now studying for an M.B.A., chose to get vaccinated after the pastor at his Pentecostal Church counseled his congregation to get inoculated. “There are rumors out there that people are dying because of the shot, and I don’t really believe it,” Frimpong says. “The first shot, I didn’t feel anything. And this is the second shot. I’m okay right now. So I’m good.”

Layla Sayed, 17, an aspiring lawyer working at a Thai rolled ice cream shop, says she got vaccinated in part to protect her mom, with whom she lives. Getting the vaccine also brought to mind the risks facing her family members living in Egypt. “They don’t have the kind of precautions we have,” she says. “They don’t have the vaccinations. They don’t have the tests. Some of them don’t even have masks, or they don’t have the money to get one. So having the privilege to be able to get something like this, it was really important to me.”

Mary Breanna Hudon, 30, a military medic and U.S. Air Force staff sergeant, injects people with vaccines. She typically gives more than 200 shots daily, working two or three days in a row, at times in 11-hour shifts. She remembers vaccinating a 9/11 survivor in his 60s who mentioned that his toxic exposures at the World Trade Center site led to kidney cancer. “So I thanked him because at that time, they were there for us,” she says. “I let him know: ‘Thank you. We appreciate you. It’s time for us to have your back.’”

Cecilia Sessions, 46, a physician and the site’s chief medical officer and a U.S. Air Force colonel, begged to be deployed to Newark. She desperately wanted to help, in part because New Jersey had one of the highest COVID mortality rates among U.S. states. “Many of the people who come in talk to us about how they’ve personally been affected and the people that they’ve lost during the pandemic. So there’s definitely a need. We had a deaf patient a couple of days ago, and I used my phone to ask for a sign language interpreter. And when the patient finished, when he got his vaccine, he just shouted, ‘Thank you, God. Thank you, everyone.’ He was so overcome with emotion. He was crying.”

Medics prepare vaccines ahead of time, often prepping for several patients at once. Each setup typically contains one alcohol wipe, one prefilled syringe and one adhesive bandage. Out of public view, medical technicians thaw trays of frozen vaccine vials to start the process of reconstituting up to 6,000 vaccine doses a day. Six doses are drawn from each vial into syringes. A U.S. Public Health Service pharmacist or a Veterans Administration nurse checks the quality of each step in this process, including a final check of every loaded syringe.

Hodan Bulhan, 39, who works as a legal assistant at a law firm, has several family members and friends who got severe COVID. They have recovered, she says, but “this [vaccination] would have been helpful if it was available at the time.” The pandemic has been a frightening experience for her. “Anything that we can do to prevent ourselves from getting ill or hospitalized is important. I believe in vaccinations. I’m a child of the 80s, and I was vaccinated and I turned out okay. So I think this will work out.”

Kajal Negandhi, 39, who works in patient safety for a drug company, says she lost a dear friend in India to the pandemic last October. After getting her second dose in Newark, Negandhi thought of her friend as well as her child and her community: “I have a little one at home. I would want her teachers to be vaccinated, so why not us? Save them, save the kids, save everybody all around.”

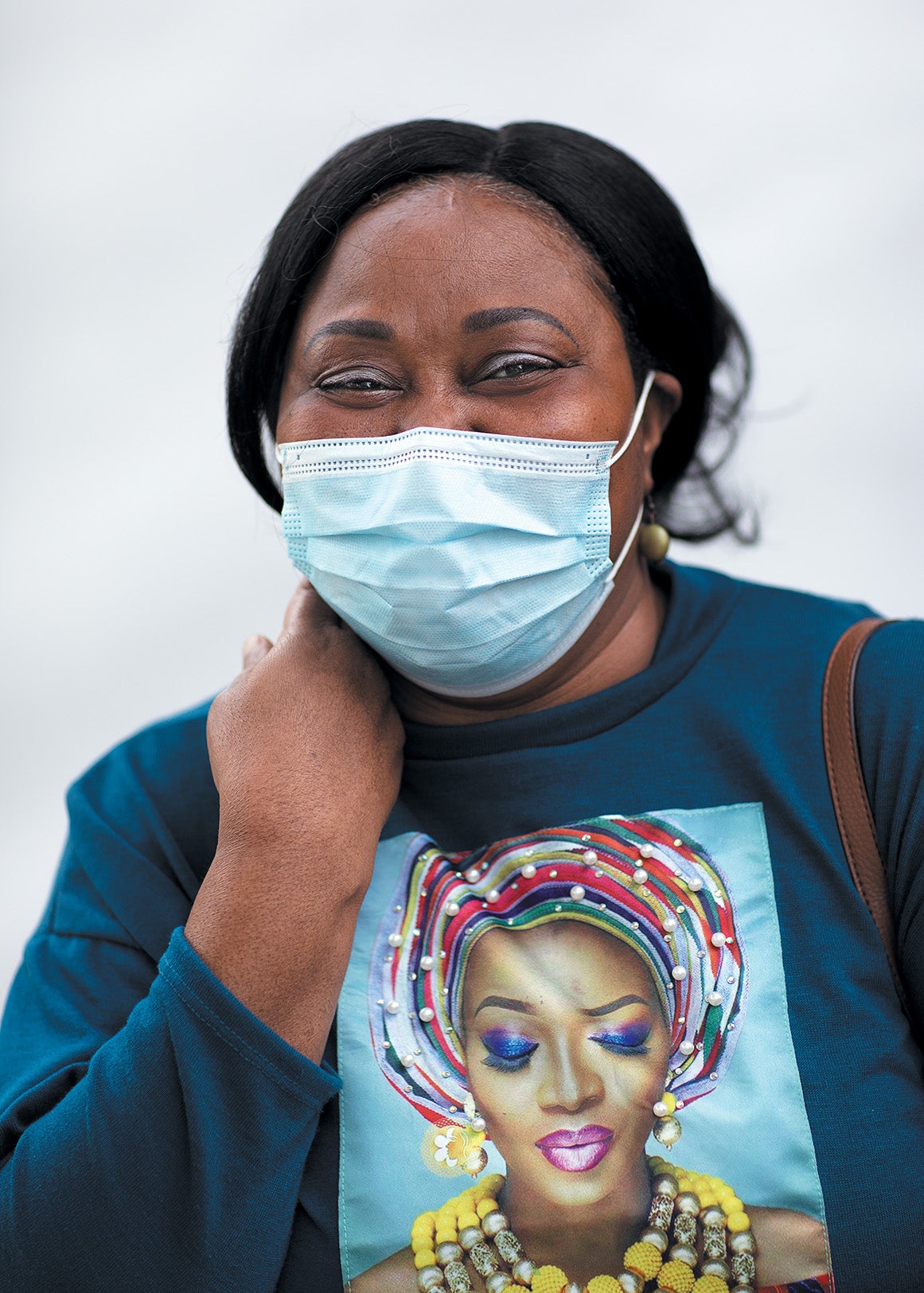

Youlanda Lee-Clendenen, 56, says she got vaccinated because she knows that people her age and those like her with underlying medical conditions are at higher risk for severe COVID. She wants to spend time with her six grandchildren and to travel. She also felt a sense of duty to get vaccinated to reduce the spread of the virus and a responsibility to provide accurate information about the vaccine to reluctant relatives in St. Vincent in the Caribbean. “They are ignorant to not take the vaccine,” she says. “But I tell them, it’s your life. If you want to go ahead and put your life at risk, that’s on you. But I’m going to protect myself.”