Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis and other conditions, is among the top causes of death in the U.S. No current therapies can prevent or reverse COPD. But thanks to amoebas, a new study has identified genes that may help protect lung cells against such harm—and potentially reverse COPD symptoms.

“I see COPD patients, so this was something very important to me,” says the study's lead author Corrine Kliment, a lung disease researcher and physician at the University of Pittsburgh. To search for potentially useful genes, Kliment and her team turned to the soil-dwelling amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum.

Amoebas have many genes that are also found in humans, but the microscopic creatures have much shorter life cycles—so scientists can use them to quickly spot genes of interest before studying mammalian models. “We often joke that humans are just amoebas with hair,” says study senior author Douglas Robinson, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

About 75 percent of COPD deaths are linked to smoking cigarettes. So Robinson's laboratory (in four short weeks) screened 35,000 amoebas, whose genes were modified to overproduce a range of different proteins, to see if any of those proteins might protect the amoebas from smoke damage. When researchers exposed all the amoebas to cigarette smoke extract, they found the ones that fared best were overproducing certain proteins important for cellular metabolism.

Next they looked for those same proteins in human and mouse lung cells. They found that cells from smokers, COPD patients and mice with long-term smoke exposure produced less of one of those proteins in particular, called ANT2.

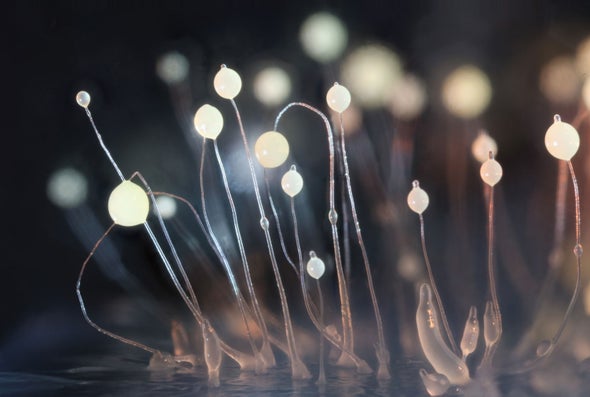

And the researchers were surprised to observe that ANT2 seemed to be playing another, nonmetabolic role as well. Looking at the lung cells under a microscope, Kliment saw ANT2 accumulating on their surfaces around hairlike projections called cilia, which sweep back and forth to clear mucus from lungs. In COPD, these cilia cannot move well; mucus then builds up and can cause respiratory failure. Kliment and her colleagues found that ANT2 boosted hydration, making it easier for cilia to sweep away mucus. Their study appeared in the Journal of Cell Science.

Kliment, Robinson and others now aim to create drugs and gene therapies that increase ANT2 production, which they hope could ease mucus buildup to reverse COPD symptoms. Robinson and some collaborators are working to start a company that will use amoebas to screen candidates for future therapies, including ones for COPD.

Gregg Duncan, a lung disease researcher at the University of Maryland, who was not involved in the study, says he is optimistic that this work may help those with COPD: “It's nice to see an opportunity to reverse the symptoms in a more durable, long-term way.”