This past winter several polls asked respondents whether they would get a COVID-19 vaccine when one became available to them. Nearly half of Americans—47 percent by one count—said “no” or “maybe.” Vaccine hesitancy has been decreasing in recent months as evidence of vaccine safety has accumulated, but this number indicates a potentially major challenge to achieving herd immunity and returning life in this country to normal. Even more troubling is that U.S. vaccine hesitancy is not evenly distributed.

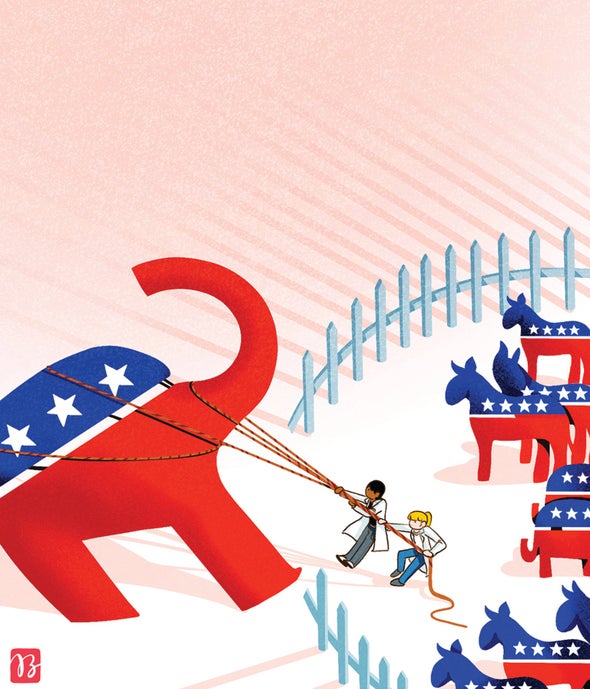

At the start of the vaccine rollout, there was a lot of talk about vaccine hesitancy among Black and Hispanic populations, but recent data suggest the problem was one more of access than of reticence. A CBS news poll in March, for example, found that vaccine hesitancy among these groups was no more prevalent than among white populations. But such hesitancy is disproportionately high among Republicans.

A different CBS news poll in January found that only 28 percent of Republicans planned to get a vaccine as soon as possible, and a whopping 71 percent said they would either “wait to see what happens to others” (42 percent) or never get one (29 percent). In contrast, 54 percent of Democrats and 38 percent of Independents planned to get the vaccine right away. In February a Monmouth University poll yielded a similarly worrisome result: 42 percent of Republicans said they would avoid ever getting the vaccine. In March the number was still at 33 percent. Moncef Slaoui, head of Operation Warp Speed under Donald Trump, said he was very concerned that people were knowingly putting themselves in harm's way and asked Trump and other Republicans to speak up to encourage vaccination.

Would that help? It's not clear. Among Americans in general, the top two reasons for vaccine hesitancy around that time were concerns that vaccines were still too untested (58 percent) and that there was a risk of side effects (47 percent). For these people, facts about vaccine safety may help allay their objections. Republican hesitancy, however, seems to have different and deeper roots.

In March longtime Republican pollster Frank Luntz led a focus group with Trump voters. Many of them stressed that they were not “anti-vaxxers” who opposed all vaccines. Nor were they “COVID deniers.” They acknowledged that the disease was real; many had family and friends who had had it, and some had been ill themselves. But they were suspicious of the federal government and had a sense that science was often oversold. CBS found similar results, reporting that 60 percent of respondents say “scientists have been wrong on the coronavirus most or all of the time” and that mask mandates and social distancing requirements do not help control the spread of the virus. And most of these people are Republicans. Luntz concluded the best approach would not be for Republican leaders to tout the vaccine but for apolitical messengers—a person's own doctor, say, or spouse—to offer facts in an honest, nonpartisan way.

Fair enough, but why do so many Republicans distrust government, including government science, and think scientists are “always getting it wrong”? A large part of the answer is that this is what the party's spokespeople have been saying for 40 years, from the early days of acid rain to our ongoing debates about climate change. It was Luntz himself who, more than 20 years ago, designed the Republican party's strategy to fight climate change by insisting there was no scientific consensus on the issue. It has mostly been Republican governors resisting mask mandates, even when science showed they slowed the spread of COVID-19. And it was, by and large, Republican governors lifting those mandates in the spring, even while Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, begged them not to.

Everyone deserves accurate information to be presented in an apolitical way and to be addressed with respect and not condescension. But the reality is that most of the science that matters most comes from the government or from scientists funded by the government. Until Republican leaders stop telling voters not to trust the government, many of them won't trust science.”