When the COVID pandemic finally retreats, the world will be different. We will have lost millions of lives—a tragic disaster that will devastate families and communities for decades to come. Other changes, of a less catastrophic nature, may not be bad things. For example, we will have lost some traditional habits and gained new ones. Take the way we greet one another: In March 2020 handshakes and cheek kisses were abruptly put on the do-not-do list to slow the spread of the virus. Once we're given the all-clear to resume those behaviors, however, we might still be wise not to do so. Even if COVID dwindles to become a mostly seasonal illness like influenza, both potentially deadly afflictions will still be with us. Do we really want to go back to rubbing our germy hands on one another or exchanging virus-laden kisses at close quarters? Not if we're wise.

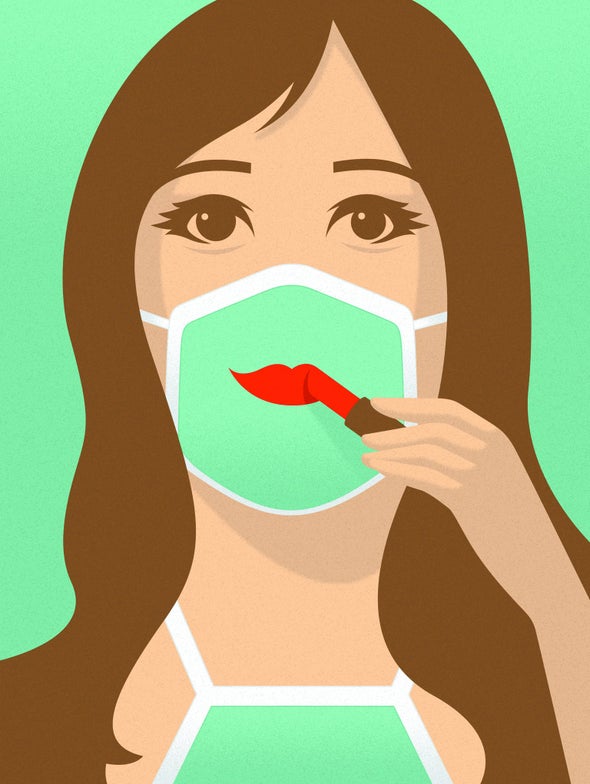

Greetings are just some of the deep-seated habits that have been cast in a new light by the year of COVID. The virus has taught us that we need a major culture change when it comes to basic public health hygiene. We learned, for example, that mask wearing is incredibly helpful in stopping the spread of all kinds of respiratory illnesses—something people in many Asian countries have known for years. Flu cases have been at record lows this year—the U.S. had at least 24,000 flu deaths during the 2019–2020 season, for instance, but so far about 450 this season. Although it is likely that many factors affected these rates, such as lockdowns, school closures and decreased travel, experts say masking has probably played a significant role. Now that most of us have impressive mask collections and lots of practice wearing them correctly, there is no excuse not to don one in public when you're under the weather. “It's considerate,” says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Georgetown Center for Global Health Science and Security. “I really hope that becomes part of our culture and that we are more conscious of how even mild infections can potentially impact other people.”

Better yet, if you may be falling sick, stay home. In some cultures, notably in the U.S., going to work with cold or even flu symptoms can seem heroic—a stoic prioritizing of work over personal comfort. This now seems ridiculous. The pandemic has taught us to take community health more seriously and to recognize our personal responsibility to avoid sickening others. All workers who have the option of taking a sick day should do so when they need to, and all workplaces must focus on giving their employees this protection—for everyone's sake. The best move would be a federal law requiring employers to offer paid sick leave. Right now almost 34 million people in the U.S. lack this benefit—that's nearly a quarter of civilian workers, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. And it is even scarcer among lower-paid workers. Predictably, people who are not paid when they call in sick are 1.5 times more likely to go to work with contagious illnesses, a 2010 study by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago found.

When companies expand their sick-leave policies, workplaces become healthier. A study carried out during the COVID crisis showed that when one company allowed more paid sick leave and encouraged employees to stay home when ill, more workers self-isolated when they got sick, and the company's offices avoided outbreaks. “This company did everything right, and it didn't have to close down,” says Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease expert at the University of California, San Francisco, who co-authored the study. “Going to work when you're sick is all too common—especially among doctors, by the way. We need to encourage a culture to stay home when you don't feel well.”

People are also much more likely to send their sick kids to school—triggering outbreaks of diseases that come home from class and infect parents—when they can't take paid time off from their job to care for them. We need employers to extend paid sick leave to include time to take care of ill family members, and we also need government support for backup child care, such as nannies who can come to a home to watch sick children if their parents must be at work.

If we do nothing else, we can at least keep up our improved handwashing habits this year.