American Sign Language (ASL) users are no strangers to video chatting. The technology—which has been around since 1927, when AT&T experimented with the first rudimentary videophones—lets deaf and hard-of-hearing people sign via the airwaves. But after the coronavirus pandemic began confining people to their homes early last year, the use of platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams and Google Meet exploded. This increased reliance on videoconferencing is altering some common elements of sign language.

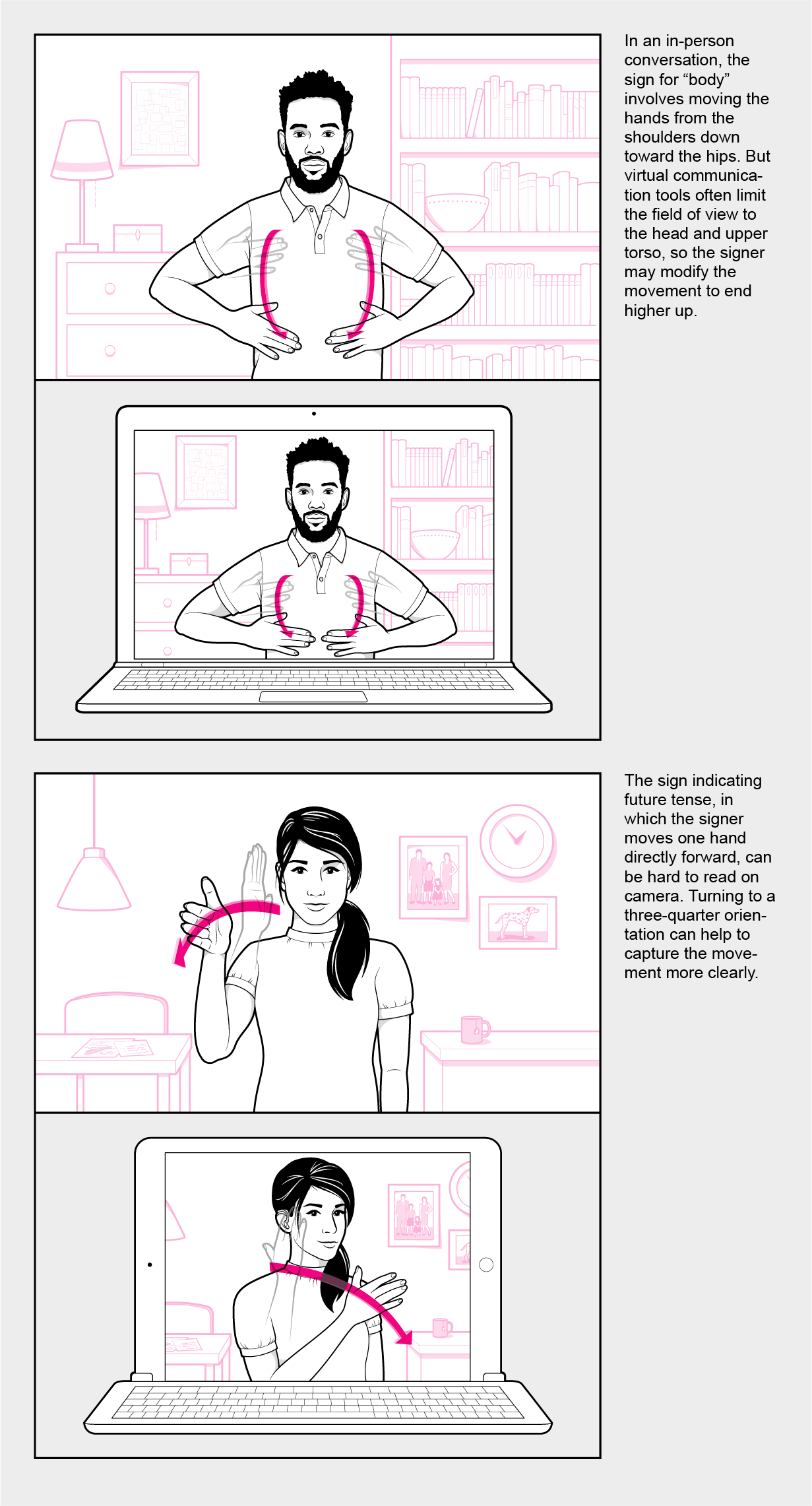

Some adaptations arise as a result of a video meeting's limited window size. “The signing space is expansive,” says Michael Skyer, a senior lecturer of deaf education at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “Even if many signs are produced easily or normally in the ‘Zoom screen’ dimensions, many are not.” The sign for “body,” for example, is usually produced by making a modified “B” hand shape and moving it from the shoulders to the hips. But to fit the reduced signing space demanded by videoconferencing, many signers have been ending it at the chest.

Signs that take up a lot of space may be harder to convey on video, but so are smaller ones with finer differences. Finger-spelled words, for example, as well as numbers and colors, all involve relatively small details formed with a single hand—which can make them harder to see clearly on a tiny conference screen. Skyer says signers must go slower and repeat themselves more often to fill in such gaps.

Signers communicating through video must also consider how they angle their bodies to convey meaning clearly. If two people face each other in person, each can easily see whether the other's hands are moving toward or away from them. This can be crucial for grammatical reasons; for example, signs representing future tense are usually made with a forward motion away from the signer's body, whereas past tense signs move the opposite way. Such nuances are sometimes difficult to detect on a video screen. Skyer is deaf and uses American Sign Language to teach in a bilingual ASL-English environment, in which a teacher typically signs in ASL and also shares content in written English. When using videoconferencing in class, he says, he sometimes has to sign with his body turned to present himself in a three-quarters view, so that signs usually seen head-on are easier to understand.

Some signs require a shared space for their meanings to be clear. Ones that involve indicating or pointing at another person simply do not work in a typical videoconferencing “room,” where multiple speakers may appear in different arrangements on each participant's screen. Julie Hochgesang, an associate professor of linguistics at Gallaudet University, says some people using videoconferencing have begun making signs such as “ask” or “give” (which require indicating an individual person) more explicit by adding a referent, a sign that clarifies the subject of a statement.

Will such changes fade after people return to in-person interactions? They might—but some experts say linguistic shifts are still inevitable. Because sign languages often involve their specific physical environment and are impossible to separate from it, Skyer and Hochgesang both suggest people should not necessarily think of each sign language as having a defined identity. “Instead I like to say there are ASL communities with varying practices and lexicons,” Hochgesang says. “Yes, undoubtedly, the long-term use of Zoom and other videoconferencing platforms (including FaceTime, videophones, and so on) will shape and constrain our language practices. But that's true for anything in our lives.... Our tools, people we interact with, and other aspects of our environment will always be a factor in our language and communicative practices.

Despite the limitations they place on American Sign Language, videoconferencing platforms can also be empowering for deaf people. Skyer says the multimodal features of these tools—which enable both video and text chat—give his students multiple avenues for learning. Instead of being constrained to one way of communicating, they can now type in written English using the chat feature or sign in ASL using the video feature, or do a combination of both—all from home.

“ASL is defined by how it is used,” Skyer says. “How it is used is not static, and the Zoom changes show us this. Words, concepts and pragmatics [the use of language in social contexts] themselves evolve and shift given new mediums of expression.”