After her teenage daughter tested positive for the novel coronavirus this past January, Jennifer Scruggs got to work disinfecting surfaces in their home in Bethpage, N.Y. Then she noticed that she couldn't smell the Lysol she was spraying. “Uh-oh—this wasn't a good sign,” she recalls thinking. “So I got tested, and sure enough, I was positive for COVID.”

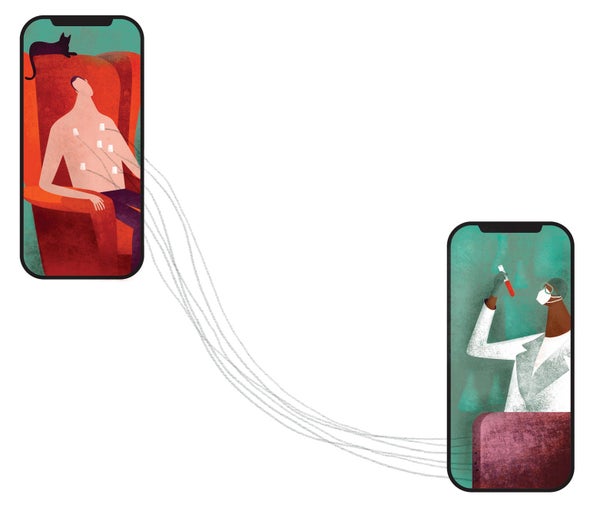

Scruggs, an administrative employee at Northwell Health, a network of hospitals and clinics based in Long Island, N.Y., heard that her employer was recruiting nonhospitalized COVID patients for a clinical trial. The goal was to find out whether famotidine, the active ingredient in the heartburn drug Pepcid, could reduce the severity of the infection. Eager to contribute to science, Scruggs was thrilled to learn she could participate without leaving home. Everything needed for the monthlong study—pills, instruments to measure her respiratory capacity and oxygen levels, a scale, a fitness tracker and an iPad—was delivered to her doorstep. Readings from the devices were transmitted via Bluetooth to the iPad, which conveyed them to the research team. Once a week a phlebotomist wearing protective garb arrived at her home to take blood samples. “Honestly,” Scruggs says, “they made it very easy.”

In the early months of the pandemic, medical research was radically disrupted for safety reasons. Nearly 6,000 clinical trials unrelated to COVID were stopped during the first five months of 2020, about twice the usual number, according to one analysis. But the outbreak has also accelerated a shift toward digital and remote research methods that make participation easier for patients and make data collection more efficient for scientists. Across diverse disciplines, study designs are being revamped to bring the trial to the patient rather than vice versa. Scientists also hope to show that sluggish processes that have long discouraged people from participating in cutting-edge research can be safely streamlined for a postpandemic era. “One lesson of COVID is that fast is possible,” says cardiologist John H. Alexander, a senior faculty member and researcher at Duke University's Clinical Research Institute.

Trials begun in the past year already reflect changing practices. The original plan for the famotidine study was to have participants come into a clinic. “But we knew that when patients are recovering from COVID at home, the last thing they want to do is to come out for blood work or any kind of follow-up. So we completely revised our protocol,” says Christina Brennan, vice president of clinical research at Northwell's Feinstein Institutes.

Alexander is co-directing a much larger, all-virtual trial comparing two anticoagulant drugs in people who have an artificial aortic valve. Patients are enrolled and followed entirely at a distance by researchers at 56 sites. “Everything is done over the phone,” he says.

At MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, thousands of studies were underway when the pandemic hit. It was not possible to alter the approved protocols, but participant enrollment and some research-related visits have moved to phone or video conferencing, says Jennifer Keating Litton, vice president for clinical research. “The big thing that we had been dying to do for years was to establish remote consenting. Now patients can do it on their phone and sign all the consent forms.”

José Baselga, who heads oncology research for pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, sees COVID as a catalyst for far-reaching changes in cancer research. Studies often call for superfluous hospital visits and tests, he says. For example, “there is nothing written anywhere that you have to do lab work every three weeks,” yet it is the norm. Baselga believes that relying more on remote monitoring of heart rate, respiration and other physical functions, along with reports transmitted daily by patients on their pain, appetite and symptoms, will be not only more convenient but safer. “Instead of waiting for them to show up in the emergency room sick and in pain, we can intervene ahead of that,” he says.

Alexander has pushed for these kinds of updates to medical research as co-chair of the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, a public-private partnership aiming to improve the quality of medical research. “If we could make it easier and less duplicative to be in trials, we would have more participation,” he says. Why, for example, do patients have to come in for separate research-related visits; why not collect research data when they come for ordinary care? But making big changes means confronting an entrenched infrastructure, and he worries that progress will fade when the pandemic ends. Baselga is more sanguine: “There is no way we'll go back to the ‘good old days.’”