In 1954 Nobel Laureate Roger Penrose, then a young mathematician, visited an exhibition on Dutch artist M.C. Escher. Inspired by Escher’s art, Penrose devised the impossible figure known as the tribar (independently from Oscar Reutersvärd, its first creator) and sent his sketch to the artist. Escher then embedded Penrose’s design into his work Waterfall, further blurring the line between math and art.

Following in Escher’s footsteps, Australian artist Michael Cheshire routinely turns geometry into the art of the impossible, using one of the earliest and most concrete materials: wood. It all started in the early 1970s with a Rotring Rapidograph high-precision pen, says Cheshire at his workshop in Brisbane. Later, in the 1990s, a book on impossible figures provided “understanding and inspiration.” That discovery, along with newly available computer-drawing software, allowed Cheshire to develop his unique art style. “I made a table with small bits of veneer, and I was hooked,” he recalls.

Cheshire thinks of his creations as wall sculptures that translate “the latest thinking to a tactile, primitive medium.” His personal connection to the rain forests of the Australian Outback near Brisbane has been key to his artistry. Using the local timbers to build his own home, Cheshire found the wood tones delightful, ranging in brightness and color from pale yellow to brown to deep red. He discovered veneers and realized that he could arrange the natural timber colors in the correct sequences and patterns to achieve myriad geometric illusions.

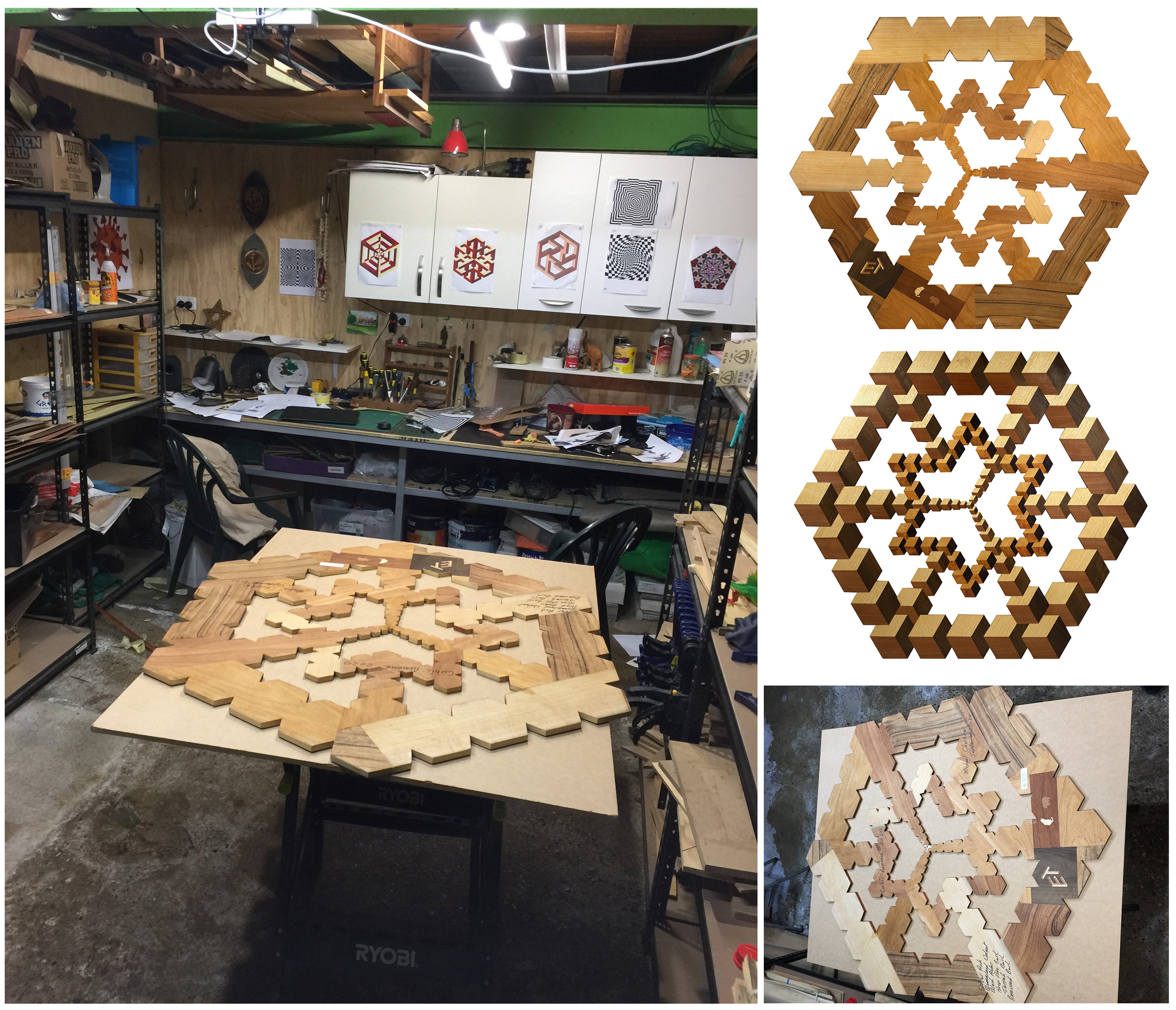

Today Cheshire’s creations start with an original design rendered in software, which determines the number, size and shape of the veneer chips he must make from each type of wood. He then cuts the veneers with a scroll saw, making manual adjustments to perfect the fit between the wood in each pattern. For the last step, Cheshire lays out the veneers and glues them on a medium-density fiberboard, which he finally backs with more veneers. “I do have a lot of setbacks as the wood can splinter easily,” he explains.

Cubic Nonsense, Cheshire’s most cent creation, featured here, conjoins six different types of native woods into a locally reasonable, yet globally impossible figure. The unassuming, palpable pieces of veneer coalesce into a three-dimensional, emergent form that defies human comprehension.

Cheshire’s impossible art exemplifies how our brains construct global percepts by sewing together multiple local percepts—in this case, individual veneers. If the relation between local elements is viable, our neural circuits will not hesitate to generate an overall form that is not.

On Facebook, Cheshire’s followers grew so puzzled that they demanded to see the back of the artwork. Cheshire was only happy to comply, revealing that the ostensibly unsolvable, apparently hovering multicubed sculpture is made of a flat board.

“I love that people can look at a still picture and have strong experiences, sometimes feeling nauseous. With impossible figures not having a focal point people tend to go round and round,” he says.