Whether it takes weeks, as US President Donald Trump has hinted, or months, as most health-care experts expect, an approved vaccine against the coronavirus is coming, and it's hotly anticipated. Still, it will initially be in short supply while manufacturers scale up production. As the pandemic continues to put millions at risk daily, including health-care workers, older people and those with pre-existing diseases, who should get vaccinated first?

This week, a strategic advisory group at the World Health Organization (WHO) weighed in with preliminary guidance for global vaccine allocation, identifying groups that should be prioritized. These recommendations join a draft plan from a panel assembled by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), released earlier this month.

Experts praise both plans for addressing the historic scale and unique epidemiology of the coronavirus pandemic. And they commend the NASEM for including in their guidance minority racial and ethnic groups—which COVID-19 has hit hard—by addressing the socio-economic factors that put them at risk. The WHO plan, on the other hand, is still at an early stage and will need more detail before its recommendations can become actionable, others say.

“It’s important to have different groups thinking through the problem,” says Eric Toner, an emergency-medicine physician and pandemics expert who has done similar planning at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, Maryland. And although the plans differ somewhat, Toner says he sees a lot of agreement. “It’s great that there’s a consensus of opinion on these issues.”

Head of the line

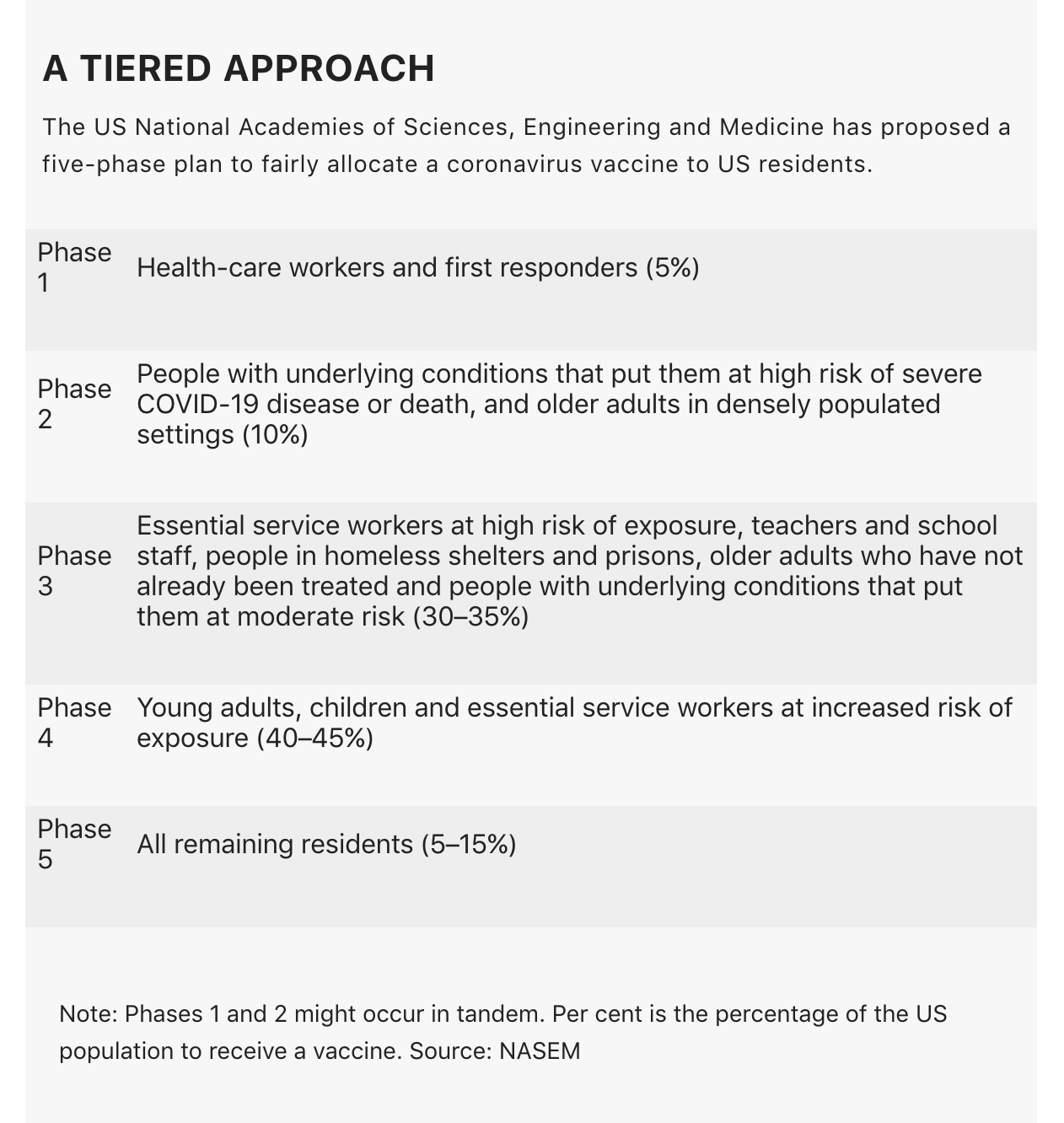

The WHO’s guidance at this point lists only which groups of people should have priority access to vaccines. The NASEM guidance goes a step further by ranking priority groups in order of who should get a vaccine first (see ‘A tiered approach’).

After health-care workers, medically vulnerable groups should be among the first to receive a vaccine, according to the NASEM draft plan. These include older people living in crowded settings, and individuals with multiple existing conditions, such as serious heart disease or diabetes, that put them at risk for more-serious COVID-19 infection.

The plan prioritizes workers in essential industries, such as public transit, because their jobs place them in contact with many people. Similarly, people who live in certain crowded settings—homeless shelters and prisons, for example—are called out as deserving early access.

Many nations already have general vaccine-allocation plans, but they are tailored for an influenza pandemic rather than the new coronavirus. They typically prioritize children and pregnant women; the COVID-19 plans do not, however, because most vaccine trials currently do not include pregnant women, and the coronavirus seems to be less deadly to children than influenza is. The NASEM guidance, in fact, recommends giving children COVID-19 vaccines during one of the final phases of its allocation plan.

Unlike the NASEM guidance, the WHO plan notes that government leaders should have early access, but cautions that people prioritized in this way should be “narrowly interpreted to include a very small number of individuals”.

“We were very concerned about the possibility that this group could serve as a loophole through which a truckload of people who identify as important could then push themselves to the front of the line,” says Ruth Faden, a bioethicist at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics in Baltimore, Maryland, who was part of the group that drafted the WHO guidance.

Hard-hit groups

Access for disadvantaged groups is addressed in both the plans. Looking to past failures, the WHO guidance urges richer countries to ensure that poorer countries receive vaccines in the earliest days of allocation. During the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, “by the time the world had gotten around to figuring out how to get vaccines to some low- and middle-income countries, the pandemic was over”, says Faden.

But the WHO proposal does not yet suggest how nations might resolve the tension between allocating vaccines in a country versus allocating them among countries, says Angus Dawson, a bioethicist at the University of Sydney in Australia, who published a review of national pandemic allocation ethics earlier this year. In other words, should harder-hit nations receive a bigger allocation of an early vaccine before other nations have a chance to dose their high-priority groups?

The NASEM was asked to develop its allocation plan by both the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which will set the US government’s COVID-19 vaccination plan, and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is coordinating vaccine and treatment trials. When tapping NASEM to create the proposal, leaders from both agencies requested that the report address how to give vaccine priority to “populations at high risk”, including “racial and ethnic groups” that have been affected by COVID-19 and have died at disproportionately higher rates than have other groups in the United States. The panel determined that these groups are vulnerable chiefly for socio-economic reasons tied to systemic racism—for example, they have high-risk jobs and live in high-risk areas—and therefore addressed the request through this lens, without singling out the groups because of their racial or ethnic identities.

“We really are trying to make sure that people of colour, who have been disproportionately impacted, will also have priority—but for the factors that put them at risk, not highlighting just their racial and ethnic makeup,” says Helene Gayle, president and chief executive officer of The Chicago Community Trust in Illinois, and who is a co-chair of the NASEM committee that drafted the proposal.

Faden says the recommendations acknowledge the current focus on racial injustice in the United States. “I was reading to see: does this report speak to the cultural moment in the United States, does it speak to racism and other forms of structural inequality? And it does,” she says.

The NASEM panel therefore proposes a lengthy list of essential workers who should get priority access to a vaccine, including grocery-store workers, transit workers and postal workers. People from hard-hit ethnic and racial groups are overrepresented in these jobs.

US states should also use the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index to help to make decisions about allocation, the NASEM plan suggests. A geography-based tool that typically guides the allotment of aid after a national disaster, it accounts for where people live, as well as health conditions that are over-represented in Black and Indigenous people, and other people of colour.

Heeding the advice

The WHO’s strategic advisory group will continue to update its guidance, first to assign rankings to its priority groups, and then to include real data from vaccine trials, such as how effective a given vaccine is in older people. Although the guidance is available to all WHO member nations, none is compelled to implement it.

In the United States, the NASEM committee is due to issue a final plan in October. Ultimately, the CDC will consider these recommendations among others while developing its own vaccine-allocation plan for the country, expected later this year.

That will be the guidance that public-health departments, doctors and pharmacies throughout the United States should follow when handing out vaccines—assuming that one has been proven safe and people are willing to take it.

Trump has been rooting for a vaccine to be ready by November, in time for the US presidential election—but a perception that the vaccine has been rushed could erode people’s trust in it, says Sandra Crouse Quinn, a behavioural scientist at the Center for Health Equity at the University of Maryland in College Park. This could make vaccine-allocation plans less effective.

When it comes to putting any of these plans into action, Dawson says, “You have to take into account the political context.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on September 17 2020.