2020 has been a historic year— and mostly not in a good way. Among many things, we saw a historic level of disregard of scientific advice with respect to the COVID-19 virus, a disregard that made the pandemic worse in the U.S. than in many other countries. But while the events of 2020 may feel unprecedented, the social pattern of rejecting scientific evidence did not suddenly appear this year. There was never any good scientific reason for rejecting the expert advice on COVID, just as there has never been any good scientific reason for doubting that humans evolved, that vaccines save lives, and that greenhouse gases are driving disruptive climate change. To understand the social pattern of rejecting scientific findings and expert advice, we need to look beyond science to history, which tells us that many of the various forms of the rejection of expert evidence and the promotion of disinformation have roots in the history of tobacco.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, most Americans saw science as something that made our lives better. Science had deepened our understanding of the natural world, which helped us to cure diseases, light our homes and bring new forms of entertainment into our lives. Perhaps most important, physicists helped to win World War II and became cultural heroes. Chemists got their due, too. As DuPont reminded us, we had “better things for better living through chemistry.” At General Electric, scientists and engineers were helping to “bring good things to life.” These were not just slogans; corporate R&D really did produce products that measurably improved many American lives. But corporate America was also developing the playbook for science denial and disinformation.

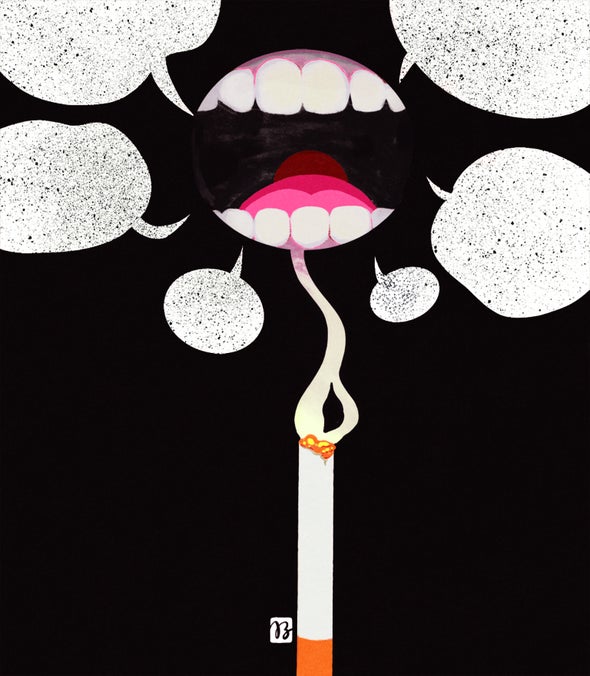

The chief culprit in this darker story was the tobacco industry, whose playbook has been well documented by historians of science, technology and medicine, as well as epidemiologists and lawyers. It disparaged science by promoting the idea that the link between tobacco use and lung cancer and other diseases was uncertain or incomplete and that the attempt to regulate it was a threat to American freedom. The industry made products more addictive by increasing their nicotine content while publicly denying that nicotine was addictive. With these tactics, the industry was able to delay effective measures to discourage smoking long after the scientific evidence of its harms was clear. In our 2010 book, Merchants of Doubt, Erik M. Conway and I showed how the same arguments were used to delay action on acid rain, the ozone hole and climate change—and this year we saw the spurious “freedom” argument being used to disparage mask wearing.

We also saw the tobacco strategy seeping into social media, which influences public opinion and which many people feel needs to be subject to greater scrutiny and perhaps government regulation. In October 2019 Congress held hearings to investigate the role of Facebook in potentially spreading misinformation. In the summer of 2020 a report from civil-rights law firm Relman Colfax suggested that Facebook posts could contribute to voter suppression. Climate scientists have complained that the social media giant contributes to the spread of climate denial by permitting false or misleading claims while hobbling responses by mainstream scientists by labeling their posts “political.”

Without a historical perspective, we might interpret this as a novel problem created by a novel technology. But this past September, a former Facebook manager testified in Congress that the company “took a page from Big Tobacco's playbook, working to make our offering addictive,” saying that Facebook was determined to make people addicted to its products while publicly using the euphemism of increasing “engagement.” Like the tobacco industry, social media companies sold us a toxic product while insisting that it was simply giving consumers what they wanted.

Scientific colleagues often ask me why I traded a career in science for a career in history. History, for some of them, is just “dwelling on the past.” But, as the bard said in The Tempest: “What's past is prologue.” If we are to confront disinformation, the rejection of scientific findings, and the negative uses of technology, we have to understand the past that has brought us to this point.”