In downtown New York, mysterious deliveries of heavy equipment were arriving at the Devlin & Co. clothing store on Warren Street and Broadway. In the middle of the night, metal rods would periodically poke up through the roadbed from somewhere below. A grand and secret project was underway, which its mastermind thought would revolutionize urban life.

Horse-drawn cart traffic was choking the city, which in 1869 housed nearly a million people. Getting around plagued residents with “filthy, health destroying, patience-killing street dust,” as a Scientific American writer put it—much of it probably dried horse manure. Alfred Ely Beach, who almost 25 years earlier, at the age of 20, acquired Scientific American with a partner, had a plan that would clean up traffic and clean the air.

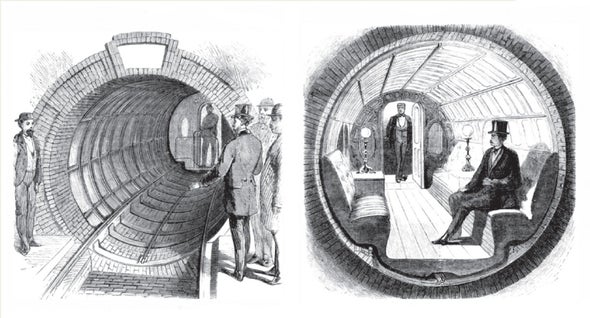

In 1867 Beach, who was a prodigious inventor, demonstrated an aboveground, pneumatically powered train inside a tube at the American Institute Fair in New York City. It was a visitor favorite. Forced-air tubes were being used to transport mail in London, and as a later Scientific American article mused, “If a package of letters could be blown through a tube, why not a package of human beings in a car?”

Beach, a chief editor at the magazine, had also published a design for a short, cylindrical tunneling machine, or shield, nine feet in diameter, made of iron and timber, that could dig a round tunnel underground by ramming forward, driven by hydraulic power. He had everything he needed to create a clean, modern transportation system for Manhattan—except for permission to build it.

The city was ruled by the notoriously corrupt William “Boss” Tweed, who among many illegal doings was getting kickbacks from the city's steampowered train and horse-pulled bus lines. Hiding his true vision, Beach managed to gain city permits to build small pneumatic tubes belowground to carry mail and later snuck through an amendment that allowed a single, large tube that ostensibly would hold the smaller tubes.

Having made money through a very successful patent agency, which he oversaw while working at the magazine, Beach put up $350,000, and the project quietly got underway 21 feet below bustling Broadway. Using the shield, workers dug the tunnel two feet at a time, reinforcing the newly exposed walls. Periodically, the crew would force a metal rod up through the soil to the road above to check that they were on course.

It is hard to keep a secret in New York City, though, and word of the project began to leak. On February 26, 1870, less than two months after it was begun, Beach revealed the finished sample section of Beach Pneumatic Transit. Lawmakers, scholars and members of the press descended to the basement of an adjacent store and stepped into a new subterranean rail station. The visitors did not find “damp and dimly lighted cellars, but commodious, airy, and comfortable apartments,” as Scientific American noted soon after. There was even a fountain. The tunnel itself, as if to highlight its cleanliness, was lined in white brick.

The day after the opening the New York Times wrote: “It must be said that every one of [the visitors] came away surprised and gratified.... And those who entered to pick out some scientific flaw in the project were silenced by the completeness of the machinery, the solidity of the work and the safety of the running apparatus.”

On March 1 the pneumatic train opened to public patrons, who paid $0.25 for a ride on the curiosity. A gigantic, 100-horsepower fan installed at the back of the station pushed an enclosed train car, rolling on tracks, about 300 feet that included a bend, to the next and only stop. Engineers then reversed the fan to create negative pressure that pulled the train back to its starting point. The one cylindrical car slowly whooshed along with just 1.5 inches of clearance between it and the tunnel walls. The car's interior was lavishly outfitted with upholstery, bright zirconia lamps and seats for 18 people. Thousands of patrons would take the joy ride in the ensuing months.

Beach planned to eventually run the pneumatic wonder the full length of Manhattan, boasting luxury cars 100 feet long. Tweed, however-infuriated at being fooled and upstaged-blocked the project and directed his administration to allocate funds for an elevated railway on the west side of the island instead. Beach also took a hit in the 1873 financial crisis and closed Beach Pneumatic Transit. He continued to work diligently at the magazine until, on January 1, 1896, perhaps in cruel irony, he died from a lack of air, perishing from pneumonia at age 69.

Three years later, after a building on Broadway burned down, workers who were clearing rubble happened on the tunnel, which had been closed off for a quarter of a century. A Scientific American article reported that the tunnel was “still in a good state of preservation, demonstrating beyond a doubt its utility for rapid transit purposes.”