Democrats and Republicans may often be at odds over climate change, but the U.S. military is not waiting for the debate to be settled. It is preparing for a hotter world, which is already altering geopolitical relations and could lead to armed conflict.

The U.S. Department of Defense breaks the menace into two parts: a direct threat to its infrastructure (think naval bases that face rising seas) and the indirect threats posed around the world if societies become destabilized. Although the first danger is relatively easy to prepare for–figure out what is vulnerable, then strengthen the infrastructure or move away from the danger—it is already proving costly and difficult to prioritize. In 2018 and 2019 the military faced nearly $10 billion in damage to its bases from climate-related impacts: Hurricane Florence caused $4 billion in damage to Marine Corps bases in North Carolina, Hurricane Michael caused $4.7 billion in damage when it leveled Tyndall Air Force Base, and Midwest flooding caused $1 billion in damage to Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. In just one year, three bases suffered more damage from climate-related threats than enemy action has caused in the past 60 years.

Although climate change will drive costs to infrastructure, the second threat—how it is driving global conflict—is altogether more complicated. Weather, governments and societies are complex systems, so predicting how each will react to higher temperatures is difficult. Yet credible voices have found clear links; a 2015 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, for example, noted that climate change fueled the beginning of Syria’s civil war by making a regional drought deeper and longer. That drought, when combined with the government’s refusal to deal with crop failures and livestock deaths, pushed hundreds of thousands of people to migrate from their farms into cities such as Aleppo and Raqqa. Once protests began in the country in early 2011, many people with little to lose and resentment toward the government joined in. The unrest turned to civil war when the Syrian government started shooting protesters, and that civil war allowed ISIS, also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, to rise, terrorizing the world.

The U.S. military does not explicitly say that climate change will directly cause wars, but it does call it an “accelerant of instability” or a “threat multiplier.” Such language appeared in the DOD’s formal 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review, its major planning document for the next four years. It also kicks off the department’s 2014 Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap, a strategic analysis of how to begin to tackle climate threats.

The Trump administration, which will withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement on climate change and has rescinded as many environmental regulations as it can, has tried to take away the military’s explicit focus on climate change. The 2018 National Defense Strategy, for instance, includes no mention of “climate change,” and a 2017 executive order rescinded Obama-era initiatives to assess and plan for the risks of climate change. When questioned in Congress, however, senior civilian and military leadership have affirmed the security threats of climate change and recommitted the military to planning for it—given that the military must plan for reality, respond to disasters and prevent humanitarian crises from sliding into conflict.

The military has not suddenly become an arm of the Peace Corps. Its mission is to safeguard U.S. interests around the world. Protecting human lives can prevent struggling countries from becoming failed states. Recent history has shown that failed states, such as Afghanistan and Syria, present real threats to U.S. national security by destabilizing regions and breeding terrorists who could threaten Americans.

The U.S. military assesses security around the world, but there are three hotspots where climate change could lead to new conflicts—sub-Saharan Africa, the Asia-Pacific region and the Arctic. A fourth theater, the Middle East, could also be on the list, but the multiple challenges of ongoing wars in Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan have precluded longer-term thinking about climate threats.

Africa: Drought and Terrorism

Geographers often judge Africa as the continent most vulnerable to unrest in response to climate change because poverty is widespread, much of the population relies on rain-fed subsistence agriculture, climate variations can be extreme and governance in numerous nations is poor. Disease outbreaks, crop failures, persistent ethnic and religious rivalries, and corruption abound. The continent’s population is expected to grow rapidly from 1.2 billion today to double that, or more, by 2050. Adding the stresses of climate change to this already dangerous brew, it is thought, could accelerate the existing threats and tip fragile states toward war.

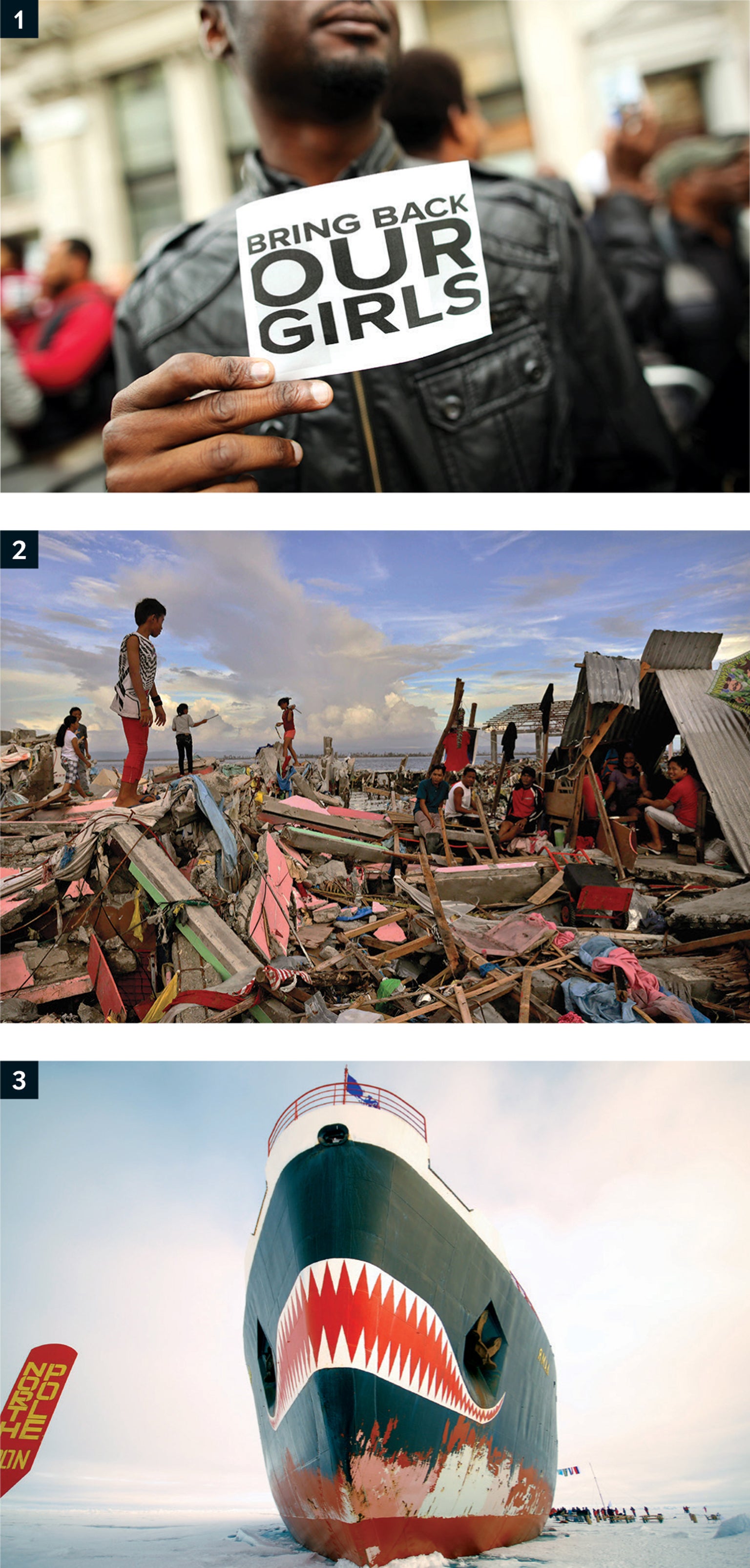

In fact, it already has. In northern Nigeria deforestation, overgrazing and increased heat from global warming have turned what was once productive farmland and savanna into an extension of the Sahara Desert. Lake Chad has lost more than 90 percent of its original size from drought, mismanagement and waste. Together these factors, along with a Nigerian government that was perceived as unresponsive, led the local population into poverty and prompted migrations to find sustenance and safety.

The violent Islamist insurgent group Boko Haram stepped into the miserable vacuum left by these factors. Though originally focused on northern Nigeria, in March 2015 the group pledged allegiance to ISIS, demonstrating a clear threat to U.S. allies and interests. A chain of causation from climate change to desertification, to food insecurity, to migration and then to conflict fueled Boko Haram’s rise.

The main mission of the U.S. military’s Africa Command (AFRICOM) is to contain existing threats such as Boko Haram and to prevent new ones from starting. (AFRICOM is one of six combat commands based on geography that the U.S. military has formed to cover the globe. Although the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the secretary of defense give direction, each command plans most of its operations.)

Scientists know that warming in Africa will lead to more extreme weather and less water availability, which will lead to lower food productivity in places that already struggle with food security. Warmer temperatures are also allowing mosquitoes to expand their range, increasing disease transmission. Those trends, in turn, could cause more poverty and migration, which could lead to local conflicts over increasingly scarce resources, thereby undermining the stability of states and leading to violent uprisings that could rear terrorists. The military’s intent is to cut this chain of causation early enough to prevent a war from starting.

One primary strategy is to help build accountable governments and government institutions, nationally and locally. To do that, the military has to know which countries are most vulnerable to climate-related conflicts and then devote resources to strengthening them.

To that end, the DOD funded a 2014 study by the University of Texas at Austin’s Climate Change and African Political Stability program. It identified the most vulnerable regions of the continent. Researchers produced granular maps that overlaid climate and other security threats, showing “hot zones” where conflict would be most likely.

One particular zone was the small Central African state of Burundi. Sure enough, in early 2015 a conflict began there when President Pierre Nkurunziza sought a third term in office, even though the constitution limited him to two. Protests and an attempted coup d’état killed roughly 500 people and displaced at least 250,000 more. A cocktail of factors—including climate change—made conflict in an already unstable country more likely. But a full-scale civil war did not erupt, because the Burundian military stayed neutral throughout the crisis. And that neutrality was a testament to the American military, which trained, equipped and reformed the Burundian armed forces over the course of a decade.

Because the U.S. military does not have many boots on the ground or fleets of ships around Africa, AFRICOM’s leaders see their role as a hybrid “civil-military” command that works with other parts of the U.S. government, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development, to prop up military and government institutions in African countries. It is ironic that one of the best ways to prevent climate change from sparking conflict has nothing to do with environmental measures.

The Pacific: Stormy Seas

There is no shortage of American military power in the Pacific, and the country is shifting even more of its overall might into this region. The new military focus on “great power competition” is clearly targeted toward a rising China. The U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM) has more than enough traditional military threats to care about, including nuclear blackmail in North Korea, maritime disputes in the South and East China Seas, tensions over the political status of Taiwan and the rising military power of China. Climate change adds two main, overlapping threats to people in the Pacific: more frequent and intense storms caused by warmer oceans, accompanied by rising sea levels. Together these developments could threaten the existence of small island states such as the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu or Micronesia. Sea-level rise could inundate key food-growing regions such as the Mekong River Delta, and storm surges are threatening the long-term viability of major population centers such as Shanghai, Jakarta, Manila and Bangkok.

In 2018 eight out of the 10 deadliest natural disasters occurred in the Asia-Pacific region, according to the United Nations.

The military’s overall aim is to maintain peace, freedom of trade and international law. Meeting those goals in this economically growing region is challenging. Of special concern to U.S. military leaders is China’s rapidly expanding naval strength and assertiveness there, which, if uncontested, could allow China to control the area’s seas. More than half of the world’s trade by ship passes through the South China Sea alone, where China is building military bases on islands it has annexed and physically expanded. The Philippines and other nations claim territory or rights to some of these islands, but Chinese leaders say the land belongs to them.

Climate change factors into the U.S. strategy to build alliances in the region. In cases of natural disasters such as typhoons, which are getting stronger because of climate change, the U.S. Navy is often the only force with the logistical experience to arrive quickly, with enough people and materials, to make a difference immediately after any destruction. China’s navy does not have the capability, and the country rarely provides aid to Pacific nations following calamities. The U.S. has solidified alliances with countries around the Pacific by intervening at their hour of maximum need.

A dramatic example occurred in November 2013. Super Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines with winds of 195 miles per hour. The storm drove water inland at 46 feet above sea level in some places. More than 7,000 people died, making Haiyan the deadliest typhoon in Philippine history. Immediately after the storm people became desperate for aid. Credible reports came in that the New People’s Army, an armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines, was attacking government convoys of relief supplies going to remote areas. In the city of Tacloban, eight people were killed, and more than 100,000 sacks of rice were looted from a government warehouse. Society was unraveling.

In response, then Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel ordered the USS George Washington’s battle group, which was on a port visit to Hong Kong, “to make best speed” to the Philippines. Once the aircraft carrier arrived, 13,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines provided food, freshwater and supplies. Their presence stopped the street violence, severing the chain between climate change and conflict.

Less than six months later President Barack Obama visited Manila to sign a new Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement that would deepen the alliance between the U.S. and the Philippines. Certainly a big motivation for signing this treaty was to counter China’s assertiveness in claiming and occupying islands in the South China Sea. But the quick U.S. response to Haiyan reminded the Philippine government and people, who historically had been skeptical of American military engagement, why it was important to have the U.S. Navy on their side.

Cementing alliances is crucial to U.S. efforts to counter China in Asia. Admiral Samuel Locklear, the recently retired commander of PACOM, said in 2013 that climate change could “cripple the security environment” in the Pacific by destabilizing the region. If an American ally always fears the next typhoon, it is unlikely to invest in the naval forces necessary to deal with traditional security threats, such as the territorial expansion of a rising power.

PACOM activities now include annual events such as the high-level Pacific Environmental Security Forum, coordinating military and civilian communications networks and helping to connect and train military personal, civilian aid workers, local governments and the U.N. The American armed forces are also helping to train Pacific militaries to fight and defeat an enemy, in part through exercises with names such as RIMPAC, Cobra Gold and Balikitan. The teams practice amphibious assaults, major naval actions and combined air defense. These multilateral exercises now also include a simulated humanitarian-assistance mission.

The Arctic: Open to Aggression

U.S. engagement in the Arctic is different. The Arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on earth. In less than a decade the territory has undergone a fundamental change in state, from an ocean world enclosed in ice to one open to human exploitation. Sea ice has diminished so extensively that both the Northern Sea Route over Russia and the Northwest Passage over Canada are now open to travel and energy exploration for many months out of the year. Indeed, the rapid melting of Arctic sea ice in 2007 was one of the catalysts prompting the military to think about climate security implications because the U.S. Navy would have a new ocean to patrol. Ironically, though, the military’s preparation for the security consequences of climate change in this part of the world seems surprisingly weak.

The Arctic falls under the U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM), but the European Command (EUCOM) also plays a role because it is responsible for any military action involving Russia, which is the preeminent military power in the Arctic. In many ways, the commands face a traditional suite of security challenges: rivalries among great powers, overlapping claims to resources and disputes over freedom of navigation.

A global rush is on to secure the oil and gas that the U.S. Geological Survey says sit underneath the ocean. Shipping companies are hurrying to build Arctic-capable ships that can transit over the top of the world. And countries as far from the Arctic as Singapore and India are pushing to join the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental organization of the eight countries that border or hold Arctic territory, to ensure their interests are represented. The DOD and each branch of the military have released Arctic planning documents focused on using multinational resources to improve cooperation. At a 2019 Arctic Council meeting in Finland, however, the Trump administration signaled a move to a more confrontational approach in the Arctic to counter Chinese and Russian activities. This approach has not yet been matched with new resources.

On paper, the international rule of law in the Arctic is strong; claims to territory in the Arctic Sea are governed by the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (although the U.S. Senate has never ratified it). The Arctic Council is widening its influence by bringing in new observer states (which cannot vote or propose policies) such as China, Italy, Japan and India.

The power of institutions can only go so far, however. In the Arctic, the U.S. Navy faces a competitor with more resources and ambition: the Russian Northern Fleet. Headquartered in Severomorsk off the Barents Sea, the fleet is the country’s largest naval operation and conducts regular exercises. It controls the biggest icebreaker fleet on the globe and currently is constructing what will be the world’s foremost nuclear-powered icebreaker.

In what are apparently direct orders from President Vladimir Putin, Russia’s military has created a Joint Strategic Command North dedicated to protecting the nation’s interests in the Arctic Circle. The command has reopened cold war bases across Russia’s Arctic coastline, including one at Wrangel Island, only 300 miles from Alaska. Long-range bombers that could test American and Canadian air defenses in the Arctic are being upgraded. And it is worth noting that Putin has continued to display a disregard for borders and international rules, flouting the global condemnation and sanctions brought on by his invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

China, too, has shown a growing interest in the Arctic, sending its two Snow Dragon icebreakers there on highly publicized tours to small communities in Iceland, Greenland and Canada.

In response to such moves by its great power rivals, the American military has begun to train surface vessels for operations in the unique environment of the High North, including a 2019 NATO exercise with an aircraft carrier above the Arctic Circle for the first time since the cold war.

This strategy is being tested as both Russia and China make very public maneuvers in the Arctic, however. To counter them, the U.S. could also show a greater “presence” with port visits to Iceland and exercises with NATO allies. History has shown time and again that when a powerful nation expands to claim more land, more sea or more natural resources, if other powers do not push back the expansion continues until a border war erupts.

Even so, NORTHCOM is reluctant to expand its Arctic presence, in part because of resources. It has said that operations in the Arctic would be extremely costly. As it stands, the U.S. Navy does not have the infrastructure, the ships or the political ambition to sustain surface operations there. The coast guard has only two icebreakers, and one of them, the Polar Star, is 40 years old. (Icebreakers are needed, even as sea ice retreats, because they provide year-round access and because ice flows are unpredictable and could trap ordinary ships.) In the 2020 defense budget, Congress approved new funding for the first new icebreaker in decades: construction has started, and it will enter service in 2023.

Does the Presidency Matter?

It took a long time for foreign policy and national security experts to persuade the U.S. military to prepare for a changing climate. That’s why it may surprise many that climate action within the military has continued, even under a skeptical Trump administration. The issue of climate change remains frustratingly political, with many Republicans dismissing it altogether.

Perhaps the more telling question is whether the military will be able to devote enough money to climate-related efforts, given competing priorities. The Arctic approach is not encouraging. The main source of funding for civilian-assistance operations by the DOD is the Overseas Humanitarian, Disaster and Civic Aid program, but its annual appropriation has declined to about $100 million even though the mission has been expanding.

Ultimately the truth always wins: the climate is changing, and the military commands will have to deal with its effects. It is certainly better to plan in advance for possible threats than to respond after the fact. Right now the military will not suffer a sneak attack from climate change—two of the six commands, at least, are starting to face the threat head-on. Whether that is enough to continue to cut the chain from climate change to conflict is uncertain.