Editor’s Note (11/11/20): On November 10, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance on cloth face masks to add that they can protect the wearer as well as prevent that individual from infecting others.

Any mask worn for day-to-day protection against COVID-19 is going to be imperfect, at least for now. Supplies of N95 respirators—the most effective mask type—should find their way to those in daily close contact with infected people. This requirement leaves the rest of us reusable cloth face coverings and single-use paper surgical masks. (The latter are also in high demand for frontline folks, so if you’re looking to buy, try to acquire fabric masks.)

“These are not going to be perfectly efficient,” says Kirsten Koehler, an occupational and public health expert who studies personal protection at Johns Hopkins University. But they can still help limit the virus’s circulation, especially if they are worn by those infected with the novel coronavirus—many of whom may be asymptomatic. “We’re trying to prevent spreading disease to other people,” Koehler says. “Hopefully the mask is helping to protect us, too.” Even with our faces covered, she adds, we should continue to perform social distancing and isolation. A handful of best practices can help make the most of our imperfect personal protection.

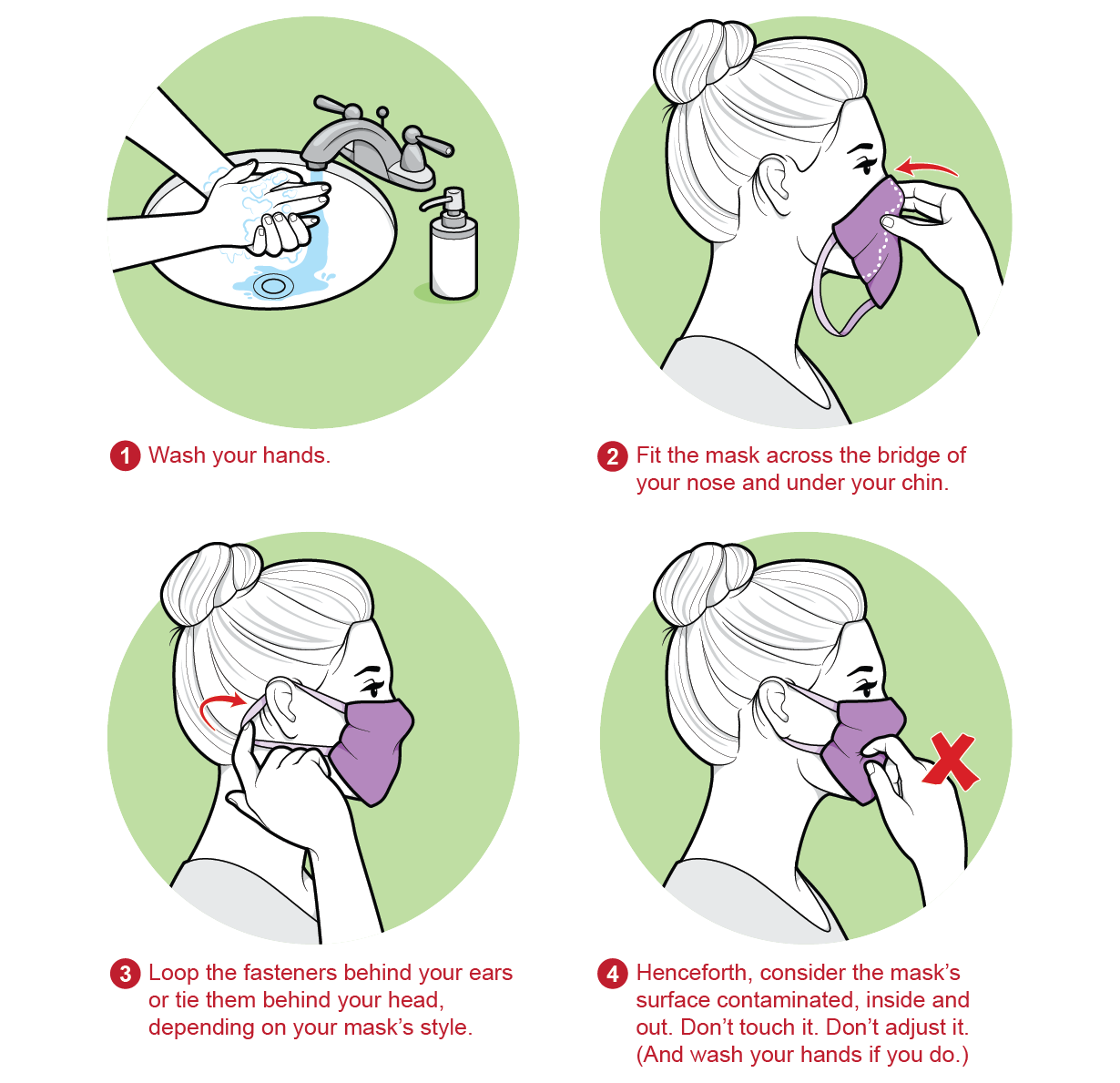

How to Put on a Mask

How to Wear a Mask

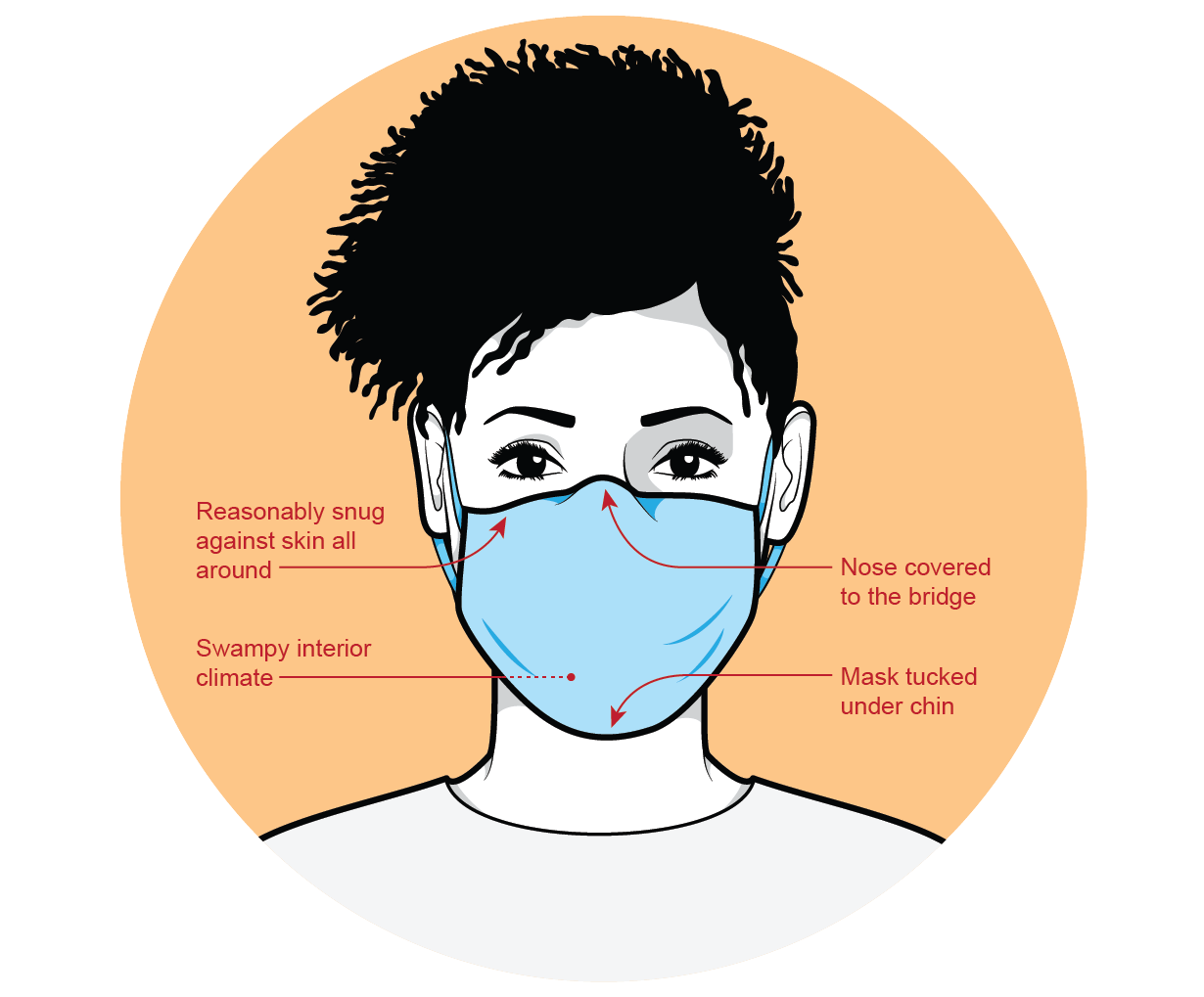

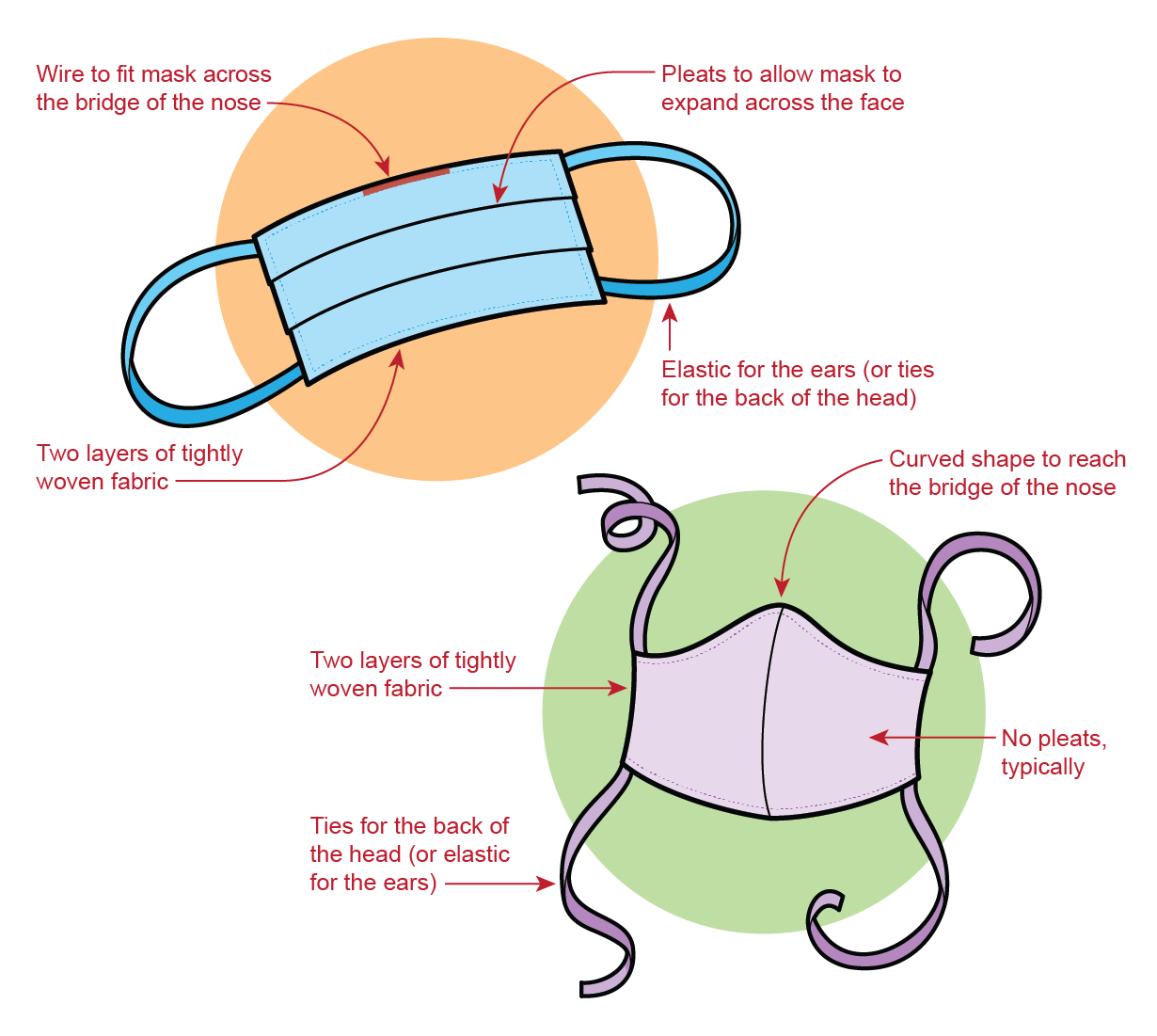

The mask should fit without gaps and fully cover your nose and mouth. Take special care to ensure a snug fit across the bridge of the nose. If your mask doesn’t have a flexible wire built in, you may be able to MacGyver a pipe cleaner, a tie for a coffee bag or another object into the role.

Are there special precautions bearded individuals should take? Koehler doesn’t think so. “None of us are getting a perfect seal around our nose anyway,” she says. “It shouldn’t make that big of a difference.”

If the mask is on correctly, air will pass through it rather than around it. Your breath will probably make it feel kind of humid and “swampy” inside.

When to Take a Mask Off

There is not a lot of data on how long a mask can be effectively worn. According to the World Health Organization, a face covering should be replaced when you have breathed through it enough for it to become damp. That effect is only likely to happen after several hours: For a trip to the grocery store, one mask will probably do. If you will be out longer, bring a spare if possible.

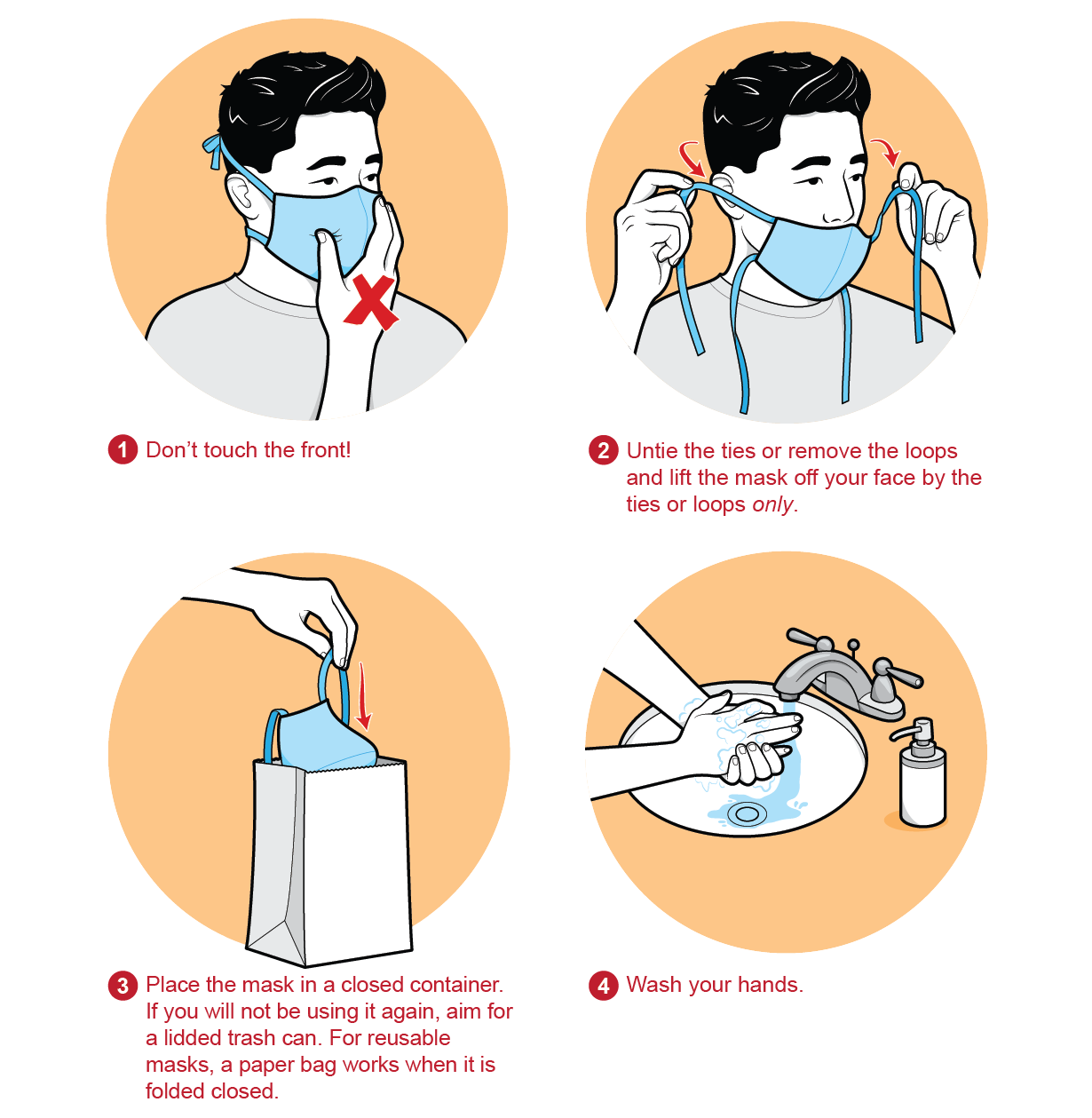

How to Take a Mask Off

How to Clean a Reusable Mask

Placing a cloth mask in a paper bag immediately after taking it off has two purposes: the container isolates the mask from accidental handling, and the paper allows it to dry out. Before wearing the covering again, let it sit in a warm spot—still in that paper bag—for two or three days. (The science here is nascent, but one study found that the coronavirus reaches undetectable levels on fabric after two days. And after a week, levels were undetectable on the insides of surgical masks, though they remained detectable on the outsides. Koehler recommends setting the paper bag on a sunny windowsill or in the natural oven of your car because the virus becomes inert faster at higher temperatures. Alternatively, if you have your own laundry facilities, you can pop a used mask straight into the washing machine with the regular laundry. A bag for washing delicates will keep mask ties from making a knot of the whole load. You can also wash a mask by hand: soak it in bleach suitable for disinfection for five minutes and then rinse it thoroughly. Face coverings should be decontaminated after each use—so have a few on hand if you are going out more often than your decontamination schedule allows.

How to Keep Your Glasses from Fogging

For the bespectacled among us, the foggy-glasses struggle is real. And in general, it means your mask isn’t fitting super well. If the material were tight across your nose, air would not be leaking from the top in the first place. Here are a few ideas to improve that fit:

Tissue: A piece of facial tissue tucked between the glasses and the mask can both push the latter into a tighter fit and prevent exhaled vapor from rising.

Tape: A bit of medical tape across the top of the mask can hold it more securely to your face at the cheeks.

Soap: A little soap on the insides of the lenses can keep fog from forming. One paper recommends dousing the inner surface with soapy water and allowing it to air-dry. A pinky nail’s worth of liquid soap, rubbed directly onto the insides of the lenses, is another option.

Materials and Effectiveness

The science on mask efficacy is spotty. A few laboratory studies have examined how fabrics protect against particles of different sizes. They were mostly done in the pre-COVID-19 era to examine air pollution and the flu. But the medical gold standard—a randomized controlled trial of masks in daily use—is difficult and has ethical concerns, because it would require knowingly exposing people to pathogens or pollutants. That said, the existing lab studies have helped teach researchers a lot about how particles interact with fabrics and paper.

Are paper or fabric masks more effective?

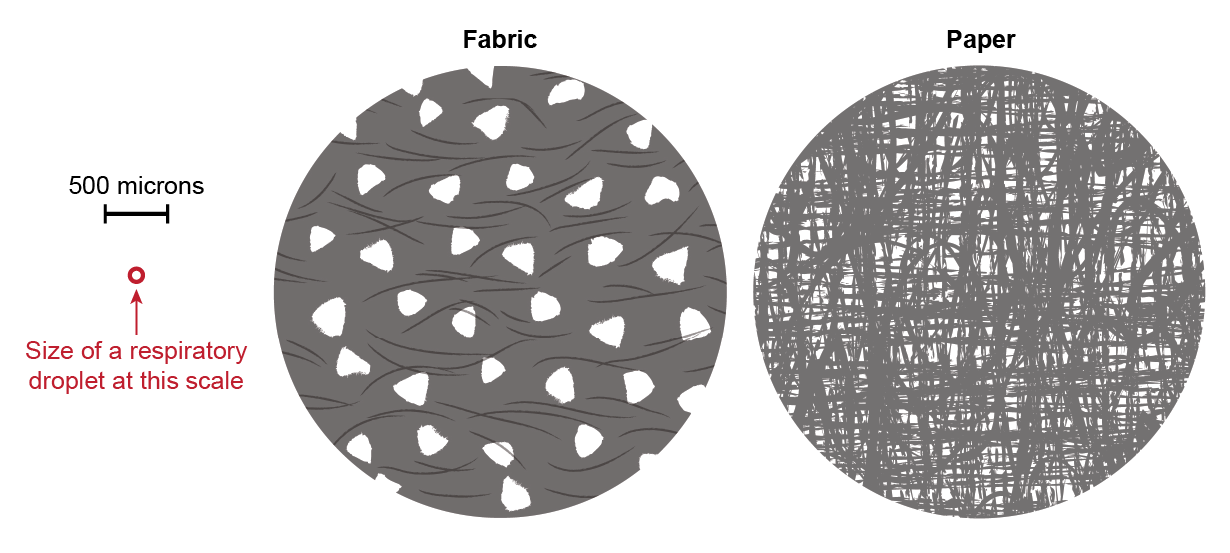

One study compared fabric and paper surgical masks’ ability to filter air pollution. Researchers examined the materials under a microscope and found fabric had a more open structure with bigger holes—often larger than the droplets believed to transmit the coronavirus. These droplets cover a huge size range: they can be wider than 100 microns—big enough to see as they fly out—down to the submicron scale.

Another study found paper masks were more effective than cloth ones at protecting against the flu. But there is more to consider than material. Fabric masks are typically sewn with two layers, which helps them trap more particles than a single cloth layer alone.

In general, even if paper face coverings are more effective, they have a shorter lifetime than cloth masks. And they are in high demand. Although the supply of surgical masks is starting to rebound, Koehler still advises the use of cloth ones. “We want to make sure that medical personnel have access to the supplies that they need,” she explains.

Okay, so what should I look for in a cloth mask?

Whether you acquire one from someone else or make it yourself, there are a few things to pay attention to. The fabric should be high-quality and tightly woven. In woven fabric, the fibers cross at right angles, whereas a knit’s structure involves tiny V’s of thread. Look for a right-angle weave and avoid knits. A tight weave—such as one you might find in a fancy pillowcase—blocks most of the light if it is held up to a window. These are, of course, difficult properties to assess when buying online.

The shape of the mask should fit your face well. Rectangular coverings usually have a length of wire built into the top so they can be molded to your face, while those with a curved design rise up over the nose a little more.

To make your own covering, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Web site has several designs for different levels of crafting skill. Designs for curved-style cloth masks are fairly widespread as well.

Experts recommend the public should avoid masks with built-in valves. They are designed to release air when the wearer exhales, reducing humidity but also allowing unfiltered breath to exit the coverings.

Are masks for the protection of the wearer or those around that person?

Both. They are most effective at preventing an infected mask wearer from spreading the virus to others. But ideally, they can also provide some protection against incoming virus-laden droplets.

Droplets evaporate as they move through the air, so they are biggest when they are first coughed out. Because cloth masks are more effective at blocking larger particles, they are most efficient at stopping the spread if they stop the droplets at their source.

Have we proved that masks themselves significantly help? Or do mask wearers tend to simply be more careful in general?

Randomized controlled studies have shown mask wearing is indeed effective against the flu, but such trials do not currently exist for masks and the coronavirus. “The evidence isn’t always as perfect as we would like it to be,” Koehler says. “Based on the aerosol science, we know that the masks are going to help reduce the transmission of these particles. Can it be 100 percent effective? Maybe not. But can it help? I think so.”

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.