A hairlike, translucent creature that builds colonies on hermit crab shells is strange enough in appearance and living arrangements, but hydractinia's oddities do not stop there. Scientists have now pinpointed a key gene—one also found in humans—that triggers this ocean floor dweller's rare ability to make an unlimited supply of sperm and eggs. It is the first time a gene has been confirmed to solely activate an organism's germ cell production, the researchers say.

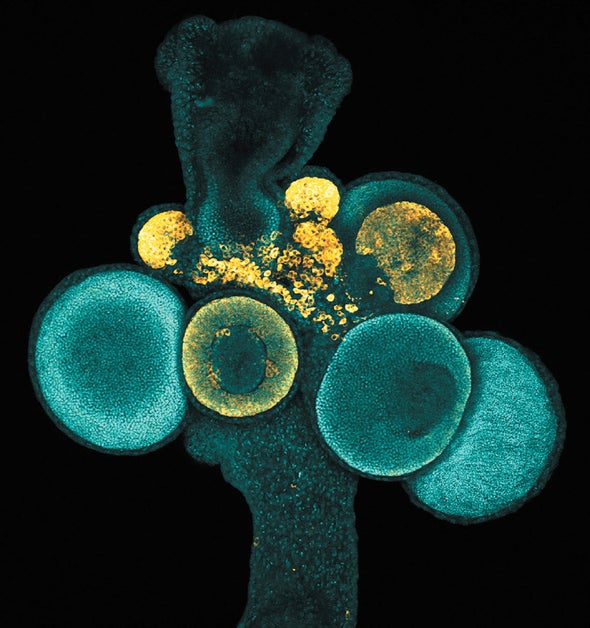

Biologist Timothy DuBuc's laboratory at Swarthmore College is one of a handful studying hydractinia, which has multiple genes in common with humans. DuBuc and his collaborators tested new ways to snip a gene called Tfap2 from the embryonic animal's DNA and manipulate its activity in particular cells, as reported in February in Science. Hydractinia's translucent body let the researchers easily observe the effect of removing the gene: once mature, the animal did not produce eggs and sperm. The team also confirmed that the gene's activation in adult hydractinia stem cells turns them into germ cells (precursors of sperm and eggs) in an endlessly repeating cycle.

Cassandra Extavour, a developmental biologist at Harvard University, who was not involved in the research, calls the study's technical advances a “heroic feat.” She says the work introduces multiple ways to interfere with hydractinia gene function, as well as the most robust gene-editing protocol to date for cnidarians—hydractinia and their relatives, including jellyfish and anemones.

In other animals scientists have investigated, Tfap2 triggers germ cells only during embryonic development—and the gene is involved in myriad other developmental processes, too. In humans, Tfap2 sparks a set number of germ cells just once during development, allowing sperm and egg production. Losing these germ cells results in sterility, and disruption of Tfap2 has been implicated in maladies such as testicular and ovarian cancer. Watching the gene in action could help researchers better understand and treat human reproductive conditions, according to the study authors.

“For those of us interested in finding the core program that makes a germ cell,” DuBuc says, “this could be the animal to do it.”