Opioids have been blamed for the deaths of at least 400,000 U.S. residents in the past two decades—but research now shows that number could be much higher.

Researchers looked at data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on about 630,000 people who died of drug overdoses between 1999 and 2016. They separated the deaths into two categories: those with and without a specific drug indicated.

For the first category, they analyzed how contributing causes of death (such as injuries and heart problems) and personal characteristics (such as age and gender) correlated with opioid involvement. They then used these analyses to calculate the probability of opioid involvement for each unidentified drug overdose, and they found that the number of opioid deaths is likely 28 percent higher than generally reported.

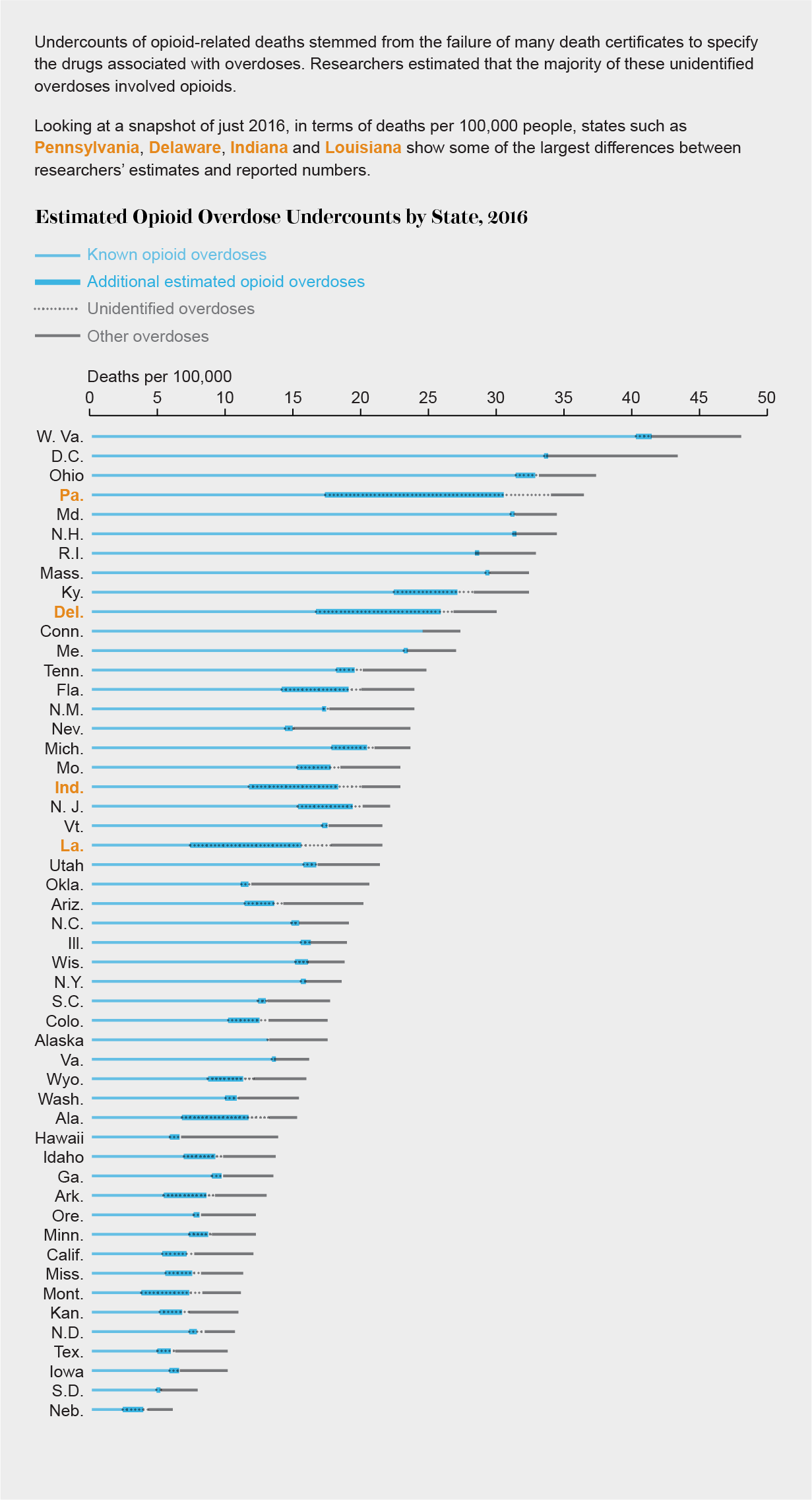

The researchers also noticed that in five states—Alabama, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi and Pennsylvania—the number of apparent opioid deaths over the seven-year period more than doubles after taking into account their adjustments.

“Opioid deaths serve as one of the main measures of the opioid crisis, and if opioid deaths are not counted accurately, the extent of the crisis can be severely misrepresented,” says Elaine L. Hill, an applied microeconomist at the University of Rochester Medical Center and study co-author. The findings appeared online in February in Addiction.

Hill says this research highlights “the potential role of state-level medical examination systems and other policies in driving high rates of underreporting.” For instance, a lack of detail in death certificates could relate to whether counties have a coroner or medical examiner, the study authors say. Either can declare cause of death, notes Alina Denham, study co-author and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Rochester. But not all coroners conduct autopsies—so Denham says coroner-based jurisdictions may be more likely to have missing information on particular drugs' involvement in overdoses. Most counties in the five states with the highest discrepancies have coroners.

Robert Anderson, chief of the mortality statistics branch of the National Center for Health Statistics, who was not involved in the study, says the research highlights what his department has known for some time: drugs are often not clearly identified in drug-related deaths, and “there is substantial variability by state and by county in the level of specificity.” Because of that, he adds, overdose mortality statistics for opioids—and other drugs—can be misleading. Using calculations like the ones in this study, he says, should help capture more accurate and geographically comparable opioid death estimates.

The researchers say they hope government officials and other researchers will use their new prediction model to calculate estimates for future deaths and to reexamine past data.