It was a November midnight, year 2000, on Nancowry, one of the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. One of us (Singh) waited in the pitch-black darkness, listening to the roar of waves crashing on the shore some 20 meters away, the stars brilliant in the sky above. Soon villagers appeared carrying dried-leaf torches. Chacho, a shaman, had died in July, and tonight was the culmination of the Tanoing festival commemorating her death. All day family and friends had ritually expressed their grief by sacrificing pigs they had raised and smashing beautiful objects they had spent hours or days crafting. (To the Nicobarese, something that took time and effort to create represents wealth, and its destruction signifies detachment from the material world.) They had decorated Chacho's home elaborately and feasted on pandanus (a starchy fruit), pork and other delicacies. Now they arrived in procession, led by Chacho's brother Yehad, a minluana (spirit healer) named Tinfus and a few other elders, followed by dozens of men, women and children, all in a celebratory mood.

Yehad and his companions carried Chacho's possessions—her tools, baskets and other things that she had treasured. Some they hung on a nearby tree; the remainder they placed on a bamboo platform at the head of the grave. Then the elders festooned the grave, wrapping meters of colorful cloth around the pole that marked the site until it resembled a standing mummy. Everyone was steadily getting tipsy from the toddy (the sap tapped from coconut palms) being passed around in coconut shells, and teenagers were flirting. A few beautifully dressed girls offered the guests tobacco and betel leaves from decorated baskets.

After the elders had finished the rites, the crowd returned to Chacho's home, laughing and joking. Tinfus installed a delicate winged figure representing her spirit, which he had carved and painted, inside the house. The mourners began singing and swaying, entering an ecstatic collective trance as they consumed more and more toddy. The joyous mood continued for most of the next day: the shaman had transitioned to the spirit world, where she would live on and protect the community.

In the Nicobarese worldview, death is the continuation of life in another form. All their ceremonies involve the veneration and celebration of ancestral and natural spirits channeled through carved and painted statues. These objects are regarded as living beings who guard the home, the village and the community. No one ever really dies. If any society has the cultural and psychological resources to cope with the staggering trauma of sudden mass death from a natural disaster, it is the indigenous peoples of these remote islands.

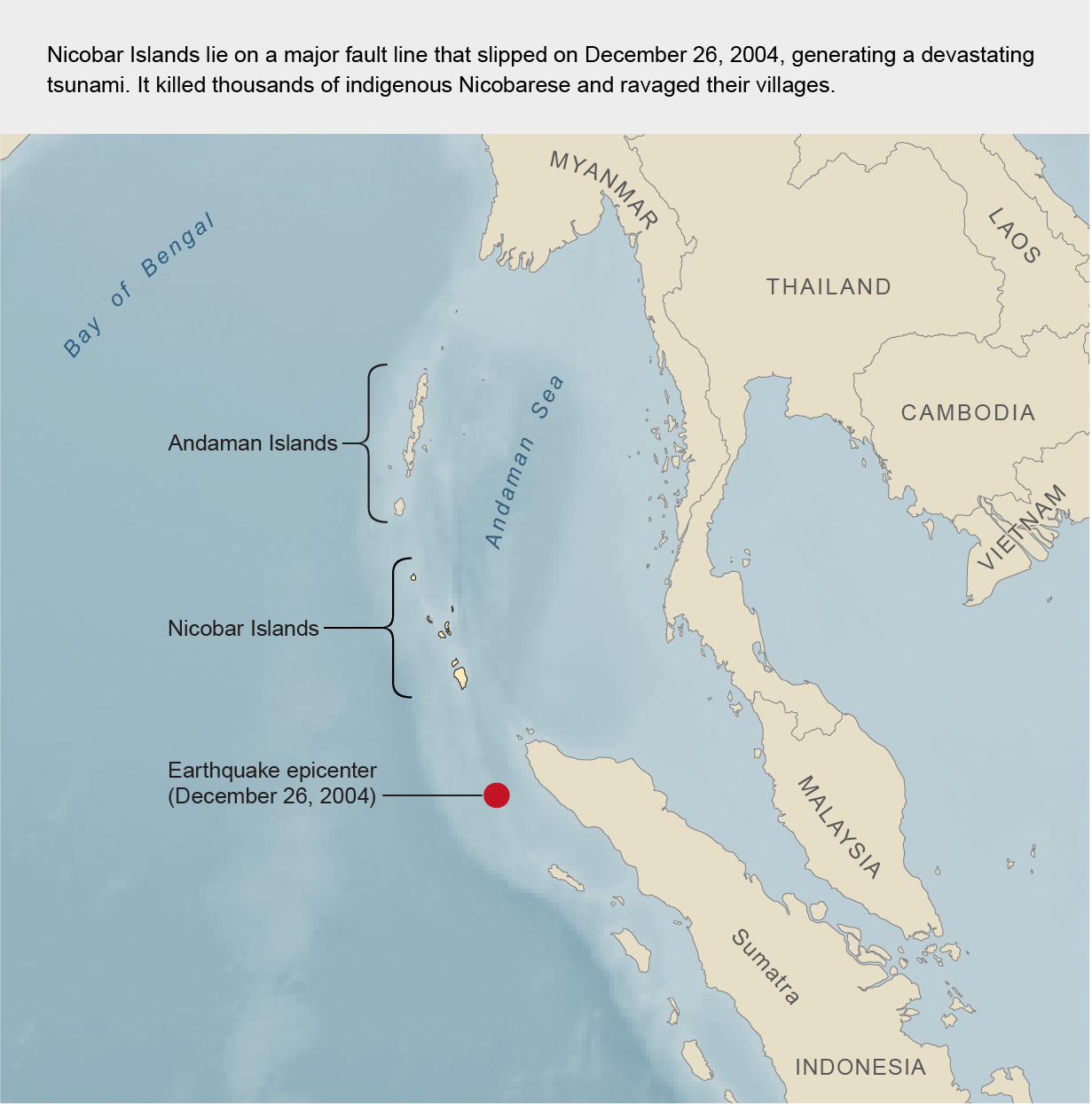

Early in the morning on December 26, 2004, the Indian continental plate slid under the Burma microplate at a depth of 30 kilometers off the western coast of northern Sumatra. The resulting magnitude 9.1 earthquake triggered a tsunami—the deadliest in recorded history. The Nicobar archipelago, comprising 22 islands with a combined landmass of only 1,841 square kilometers, lay along the fault line and very close to the earthquake's epicenter. Waves more than 15 meters high hit several times, washing clean over the smaller islands and taking with them entire villages. Tens of square kilometers of land sank under the water because of rupture and submergence; the beautiful island of Trinket broke into three pieces. Official numbers put the human toll on the Nicobars at 3,449 missing or dead, but estimates from independent researchers were as high as 10,000. (The population was 42,068 according to the 2001 census, with about 26,000 being ethnic Nicobarese.) Some 125,000 domestic animals were killed, and more than 6,000 hectares of coconut plantations, 40,000 hectares of coral reefs and almost three quarters of the houses were destroyed.

Tradition saved a few people. The chief of the village of Munak on Kamorta Island remembered ancestors' warnings about the aftermath of a colossal earthquake and urged the villagers to flee from the beach. Fortunately for them, the island has an elevated hinterland; no one from Munak died. And incredibly, many from Chowra Island were able to swim back after having been swept away by the giant waves.

The magnitude of the catastrophe led to a massive humanitarian response. More than $14 billion was mobilized, 39 percent of which came from voluntary private donations, to help tsunami victims around the Bay of Bengal and elsewhere. The Indian government—which had inherited the Nicobar Islands from the British Empire in 1947—launched a rescue-and-relief operation, and aid agencies arrived in force. Over the ensuing months and years these benefactors inundated an essentially isolated society with packaged foods, a wide range of electronic and consumer goods, and enormous cash handouts.

It might seem that such a generous effort would have left the Nicobarese far better off than before the tsunami. But the culturally insensitive aid undermined what was historically a resilient society with centuries-old institutions for independent and democratic decision-making. It ended up bringing a formerly close-knit community to the point of disintegration, with many of its members beset by alcoholism, diabetes and other formerly alien ailments. Now, 15 years later, the desperate plight of the islanders raises questions about the effectiveness of humanitarian aid that is driven by the priorities of donors rather than of recipients.

Every year the world experiences approximately 350 natural disasters, which harm millions of people. Over the past three decades nation-states and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have aimed to reduce the impact of these tragedies through prevention, mitigation and preparedness. Unfortunately, however, governments and other actors often regard indigenous cultures “as being inferior, primitive, irrelevant, something to be eradicated or transformed,” according to an assessment by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. These communities become especially vulnerable during disasters, with economically and politically dominant sections of modern society imposing ideologically motivated changes on them, forever alienating them from their culture and territory.

We are two anthropologists whose studies of the Nicobarese, conducted independently, span two decades and have given us deep insight into the society and culture before and after the tsunami. Singh conducted his fieldwork between 1999 and 2009, whereas Saini has been studying the indigenous peoples since 2010.

The Nicobarese migrated to the archipelago from the Malay Peninsula thousands of years ago and speak an Austro-Asiatic language. Before the tsunami they subsisted by hunting, foraging, raising pigs, and fishing in the rich coral reefs surrounding the islands. Some extended families, called tuhets or kamuanses, grew crops such as tubers, oranges, sugarcane, lemons, bananas, yams, papaya, jackfruit and, especially, coconuts, many of which they traded with outsiders. The entire family, made up of three or more generations, tended the orchards together, singing, joking and enjoying toddy; work and leisure were integrated. Social capital—how much help one could summon from friends and neighbors in times of need—varied and was considered a significant form of wealth. But social codes ensured that no one suffered from want.

For centuries ships sailing between India and China anchored at the Nicobars to replenish food and other supplies during their long voyages. In 1756 Danish settlers colonized the archipelago, eventually giving way to the Austrians, the British, the Japanese (during World War II), the British again and then the Indians. None of these occupations left a significant mark on the indigenous culture. In 1956 India introduced legislation limiting entry to the islands to administrators, military personnel and select businessmen and settlers. The Nicobarese began drying coconut flesh into copra, which they bartered with private traders or local cooperatives for rice, sugar, kerosene, cloth and other goods not produced on the islands. Cash rarely changed hands.

But when Singh reached the archipelago three weeks after the 2004 catastrophe, nothing was as it had been in the past. The coastline was unrecognizable, with the sea washing over the remains of many villages. Smashed corals, downed trees and other debris impeded access by boat, and SUVs got stuck in swamps, requiring arduous treks.

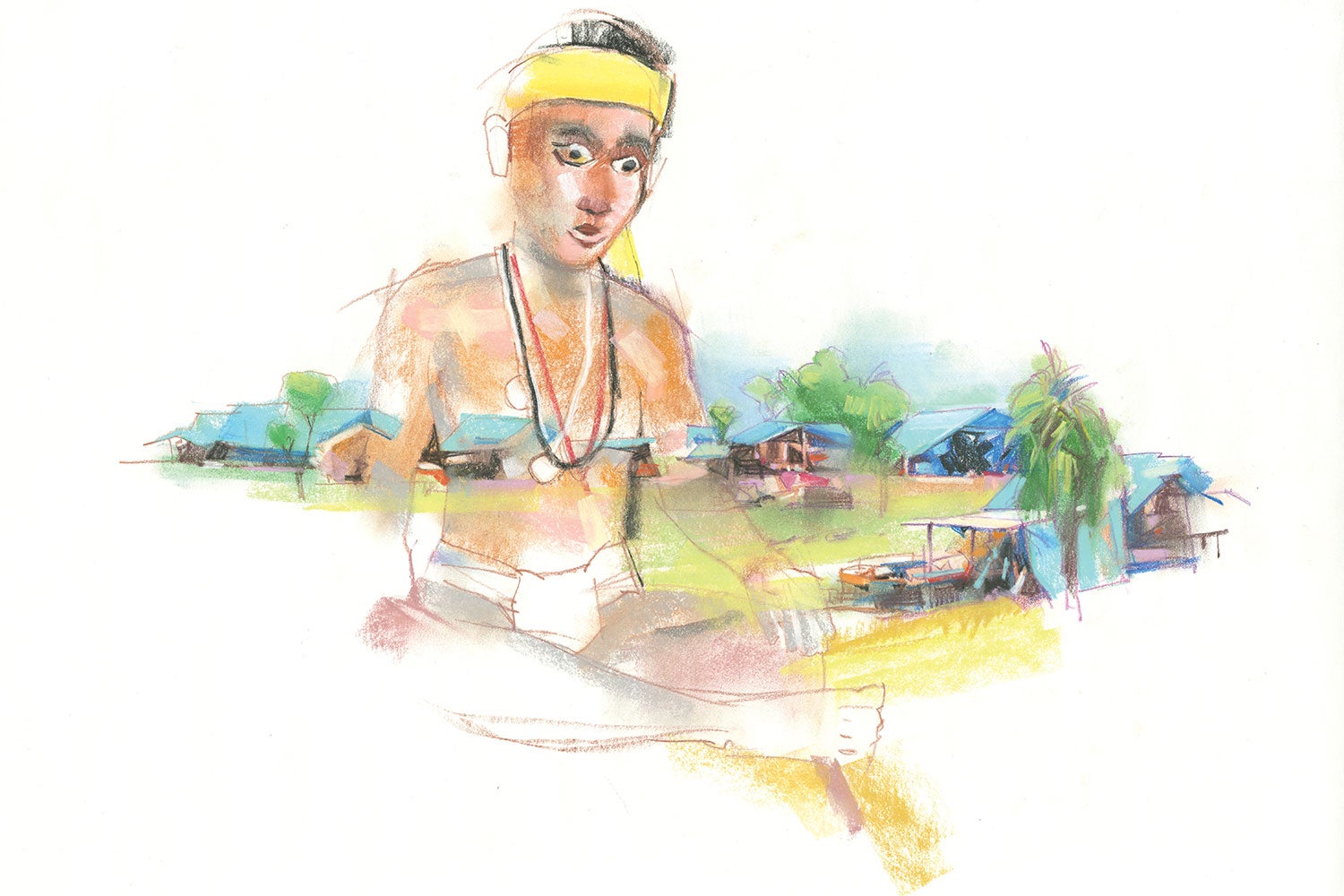

More jarring, however, was what had happened to the people. The Indian armed forces had evacuated almost 29,000 survivors—roughly 20,000 of whom were Nicobarese, including everyone from six of the smaller islands, such as Trinket, Chowra and Bompoka. The local administration, based in the region's capital, Port Blair on South Andaman Island, had accommodated them in 118 relief camps in the higher hinterlands of the remaining islands. Crammed into tents rigged out of blue tarpaulin, they had received clean water and food but little else. Many were still in shock.

It was imperative that the people of Bompoka return right away to construct shelters, tend to the orchards and plant vegetable gardens to ensure future food security, said Kefus, the island's chief. He and other elders feared—presciently—that prolonged separation from their islands could mean the extinction of their roots and their identity. “We may die, but we have to go back,” declared Jonathan, the chief of Chowra. Several chiefs asked government officials for boats and tools. The administrators advised, however, that a major aid effort was being planned by the Indian government in New Delhi (which directly controls the archipelago), which the refugees would forgo if they left. That promise left many of the camp dwellers confused, unsure of whether to rely on their own resources and traditions or trust the officials. Most decided to wait and see.

In the following weeks and months relief materials started to arrive, often poorly matched with the needs and the culture of their recipients. By the middle of 2005 the Nicobarese were living in shelters that the administration had constructed out of tin sheets. The government was providing them with rations and medicines; NGOs supplied other relief materials, including processed foods and consumer goods hitherto unknown to the indigenes. Many were unusable. Camp residents received wool blankets (unfit for a hot and humid climate), saris (worn by Indian women but alien to the Nicobarese) and a range of electronics (where the electric supply was either fitful or nonexistent).

The Indian government's approach to dispersing the aid compounded the problems. Officials consulted with the aid recipients on several issues but preferred to work with inexperienced and impressionable youths who could speak Hindi or English. These so-called tsunami captains could not effectively represent the community and ended up becoming the yes-men of the administrators. The authority of elders, who were previously the decision makers, weakened, engendering conflicts between generations and consolidating power in the hands of the administration.

With the assistance of the tsunami captains, the government deposited large compensations for tsunami damage into newly opened bank accounts. Without exception, nuclear families headed by men got the money, undermining the joint family system and the status of women, who had previously played an important role in making key economic decisions. Their heads turned by unfamiliar power, several of the captains favored their own families when it came to identifying aid recipients, which provoked disputes among them.

All the while the Nicobarese languished in the sweltering, rattling tin cubicles; Mohoh of Kondul Island said he felt like a “caged bird.” The cramped shelters offered no space to plant vegetables or raise pigs. The forests were full of fallen timber, but there were no axes to chop it with so they could construct houses. The creeks of the evacuated islands were replete with fish and crab, and the sowing season was around the corner, but most of the Nicobarese were stuck in the camps, dependent on relief rations. Some felt they were being turned into beggars. “We can manage on our own,” said Hillary, captain of Tapong, a village on Nancowry Island. “We don't need biscuits and chips. We need to make our homes and plant our gardens. Give us tools if you wish to help us.”

Mild protests erupted across the islands. The Nicobarese needed the space to grieve and to rebuild their lives in culturally prescribed ways. “Leave us alone or we are sure to die,” said John Paul, a leader from Katchal Island. These pleas fell on deaf ears. Many elders, such as Paul Joora, chief of Great and Little Nicobar, foresaw that “one day this aid will break the Nicobarese's heart.” But because of conflict with younger leaders and confusing signals from the administration, the elders could not prevail. Additionally, Nicobarese culture, being based on achieving consensus, makes it difficult for the people to express disagreement; they could not emphatically protest whatever was imposed on them.

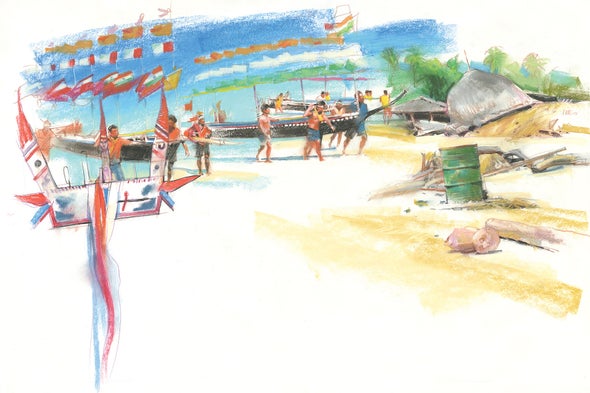

A few of the Nicobarese refused to give in. While in camps on neighboring Teressa, the people of Chowra, who had exceptionally strong traditions, built canoes with tools they had salvaged from the more intact villages. The canoes enabled them to repeatedly visit Chowra to clean debris, plant orchards and repair houses. Eighteen months after their evacuation, they returned home for good, with more than 100 small canoes and 10 festive canoes, used in celebrations, which they had spent their time in exile building.

By the time the government finished building permanent shelters for the Nicobarese refugees, in 2011, their society had been irrevocably changed. During their years in the relief camps the indigenes had come in close contact with Indian settlers, who looked down on them as “primitives” who were seminude and ate raw fish. Over time many of the young people internalized these views and came to be ashamed of their culture. The cash from the government enabled them to buy things that gave them the look and lifestyles of outsiders: televisions, motorbikes, mobile phones. The yardstick of wealth became the possession of modern commodities. Settlers and traders fleeced the gullible Nicobarese, rapidly emptying their bank accounts.

With money, free rations and enforced idleness for years on end, many of the Nicobarese gradually lost their motivation to work. Their diets shifted toward spicy Indian dishes and fast foods. Their prolonged inactivity and dependence led to depression, and many found solace in alcohol much stronger than fermented coconut sap. Though prohibited by the 1956 protection act, sales of Indian-made foreign liquor (IMFL) such as whiskey and rum, supplied by settlers and traders, shot up.

The government launched some livelihood-regeneration programs to engage the idle Nicobarese, but most were ill conceived. For instance, when officials introduced community plantations, they did not understand that land ownership in the Nicobars was vested with the lineages, which distributed usage rights among their constituent nuclear families. Whoever planted a tree owned it, but the land remained with the tuhet or kamuanse. Severe conflicts arose if anyone attempted to plant a tree on land that had not been granted by the lineage.

When the 7,001 permanent shelters were finally completed, they triggered yet another set of crises. Before the tsunami a typical Nicobarese village lay near the coast within a bay, often sheltered behind mangroves. Outrigger canoes provided easy access to other villages or to nearby islands. The huts were raised on stilts for protection from poisonous reptiles and from flooding during monsoon storms; pigs and chickens lived in the shade below. Designed for the tropics, the houses were extremely comfortable. The entrance usually faced the sea, the roof was thatched, and walls and floors were made from split bamboo that allowed breezes to move freely in and out.

But the administration constructed the permanent houses, called tsunami shelters, at higher altitudes that were far from the coast. Building contractors brought in shiploads of imported materials—prefabricated structures, steel columns, clapboards, concrete blocks, iron pillars and galvanized iron sheets—as well as hundreds of laborers from elsewhere. Many of them encroached on Nicobarese land and ended up staying permanently.

When their roofs leaked or their walls fell, the Nicobarese could no longer repair their own homes. They had to beg the authorities for help. Worse, while designing and allocating these homes, the government split the extended families into several nuclear households, undermining the very basis of Nicobarese society. In the past, the lineages had supported all within them and also helped related families in times of need or during the organization of large ceremonies. With their fragmentation, the strong social support system that the community had enjoyed collapsed, leaving its members vulnerable at a critical juncture.

For some the consequences were even more devastating. The authorities declared some islands uninhabitable and constructed houses for their former residents on other islands. The cleavage from their ancestral lands, with which they had deep spiritual and emotional bonds, caused these people tremendous suffering. “We miss our villages, but they will also be missing us,” Paul Joora grieved. The homeland, inhabited by ancestral spirits, was a living being, and the severing of ties with it was more painful than the loss of a family member.

In addition, over the years prolonged stress, sedentary lifestyles and a taste for processed foods had taken a toll. Previously unknown ailments such as hypertension appeared. The islands lack modern medical facilities, and most of the traditional healers—with their extensive knowledge of plant-based medicines—had perished during the tsunami. The Nicobarese began to die of heart attacks, diabetes, injuries, respiratory diseases, pneumonia, malaria and other diseases. Alcoholism became a scourge as well.

After allocating the last tsunami shelters in 2011, the administration abruptly stopped providing aid. As the cash ran out, addicts could no longer buy IMFL and began to consume junglee, an illicit and toxic mix of ethyl alcohol, urea, battery acid and other chemicals that mainland laborers had introduced to the Nicobarese during the reconstruction phase. “Junglee will kill more Nicobarese than the tsunami had,” predicted Ayesha Majid, who chairs the Nancowry tribal council.

Many of the indigenes believe that their perpetual sadness is the root cause of disease and death among them. “We may seem alive, but deep inside we all are dead people,” despaired Chupon, an elder of Nancowry. Tinfus, the spirit healer who had participated in Chacho's joyous funeral ceremony, echoed the sentiment. “The Nicobar is dying,” he said to Saini in 2014. In a soft, shaky voice, Tinfus explained how the kareau, or ancestral spirits, had always protected the Nicobarese from evil spirits. But of late, his people had lost faith in their traditional wisdom and trod a path of self-destruction. He prophesied that tsunami aid would end up ruining generations of Nicobarese. His speech was long and punctuated by thoughtful pauses; suddenly, in the middle of a sentence, he broke down in tears. In September 2018 Tinfus, one of the last minluanas, passed away at the age of 80. His death marked the end of an era in the Nicobar Islands.

Since the tsunami the Nicobarese community has lost its social cohesion, spiritual traditions, rules of sustainable resource use, and other immaterial attributes that once ensured its resilience. Their material consumption (as measured by weight) has increased sixfold, and their consumption of fossil fuels has increased 20-fold. In the absence of continued aid or well-paying jobs, they can only tread a path of hopelessness about meeting their expanded wants with their limited means. With the compensation money exhausted and few livelihood options in the Nicobars, many of the islanders are migrating to Port Blair, the capital, to seek work. There they live precariously, facing exploitation and racism from mainstream Indians. Christopher, secretary of Teressa's tribal council, told Saini in 2018 that the mainlanders abused them verbally and physically. “It hurts,” he said. “But what can we do?”

We believe that the fallout of misguided assistance in the Nicobars could have been averted. This close-knit community with a rich traditional knowledge base needed no outside experts to determine how to deal with its post-tsunami predicament. In the words of Rasheed Yusoof, spokesperson for Nancowry's tribal council, the Nicobarese needed only “listening ears” to get what little they needed from outsiders. With NGOs and government officials convinced that they knew best, however, the initial determination of the Nicobarese to rebuild their futures dissipated in a stream of inappropriate aid, ultimately leaving them a sedentary, depressed and disoriented people.

In 2015 a U.N. conference formalized guidelines for preventing, mitigating and preparing for disasters while also resolving to “Build Back Better” (BBB)—that is, to leave the victims better off than before the disaster. Yet case studies from places as diverse as Haiti, Nepal and the Philippines show that practitioners of the BBB approach have repeatedly failed to account for the specific needs and preferences of those they seek to help. “The promise to not re-create or exacerbate predisaster vulnerabilities has generally been unfulfilled,” concluded researchers Glenn Fernandez and Iftekhar Ahmed in a 2019 review of literature on BBB. Seen against this backdrop, the lessons from the fallout of aid in the Nicobars become even more relevant.

Rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all attitude to disaster relief and rehabilitation, recovery efforts should rely on context-sensitive measures that recognize cultural diversity, learn from traditional knowledge, ensure the active participation of affected peoples, build resilience and reduce vulnerabilities. Instead of trying to erase differences, those who administer aid need to protect and celebrate cultural diversity where it still survives and to foster the principles that guide human and planetary well-being.

Fifteen years after the tsunami, many of the Nicobarese regret having trusted the promises of their rescuers. Some are now going home. “We have no future here,” declared Portifer, who lived in Trinket but now resides on adjacent Kamorta Island, in December 2019. “Many of us are planning to go back.” Trinket was only 36 square kilometers to begin with and was reduced to 29 by the earthquake and tsunami. To an outsider, life on the fragmented island may seem precarious, with man-eating crocodiles roaming the coast, but seven Nicobarese families have already returned, choosing the perils of the ocean over those of modern civilization.