Ralph DeGayner knew he was seeing the work of a serial killer.

All of the victims had been ambushed and mutilated; many had their throats ripped out. Every morning for several weeks DeGayner, a lanky octogenarian, found the bodies buried under leaf litter along Key Largo’s route 905, a county road that runs through the Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge. The more disemboweled woodrats DeGayner encountered, the more his disappointment turned to rage.

“It was the cats,” he says, his blue eyes flashing in the Florida sun. “That’s exactly how they kill. I didn’t need more proof than that.” Returning to the site of the massacre, even eight years later, filled DeGayner with ire. He turned north, glaring toward the abutting Ocean Reef Club, a gated community home not just to millionaires but also to hundreds of feral cats.

The plight of the endangered Key Largo woodrat became DeGayner’s personal crusade late in life. To occupy his time when the conditions were not right for fishing, the retired hot-tub salesman began volunteering at the wildlife refuge, which opened in the late 1990s. He was quickly taken by the cinnamon-colored rodents, which build large, meticulous nests with a precision he found endearing. Woodrats had long eked out an existence under a thin stretch of the lush canopies of Key Largo’s semitropical forests, where they shared their neighborhood with crocodiles, snakes and raptors. The population had managed to hang on even as much of its habitat was razed to make room for pineapple plantations, a missile silo, oil derricks and luxury condos. But the cats were a different kind of menace. For one thing, not everyone agreed that cats were a menace at all.

Fifteen years ago, in a last-ditch attempt to save the woodrat from extinction, conservationists at the refuge teamed up with Disney (with its Florida presence and rodent mascot) to begin a breeding program at the Animal Kingdom in Orlando. Over several years wildlife biologists successfully bolstered the woodrats’ numbers in captivity. The real test, though, would be surviving back in Key Largo.

DeGayner was sure the woodrats would make it if he could keep the feral cats out of the refuge. He was not alone. Local conservationists had repeatedly asked the Ocean Reef Club, which fed and cared for the cats through a program called ORCAT, to figure out how to keep them contained. But ORCAT demurred: the cats were being scapegoated for a long list of problems, and anyway it would be impossible to restrict them all to the 2,500-acre property.

Over several weeks in 2010 and 2011, biologists released 27 tagged woodrats into the refuge. Within weeks cats killed every one of them. “They spent millions of dollars to show that cats eat rats,” DeGayner says. The breeding program was scrapped. And the antagonism between the cat advocates and the conservationists intensified.

An Alternative Solution

Humans did not domesticate cats as actively as they did dogs. As a result, there are far fewer genetic differences between house cats and wildcats than between dogs and wolves. But cats have lived alongside humans for more than 10,000 years. Grain stored by early farmers attracted rodents, and the rodents lured cats, which then stayed for our food scraps (and maybe a scratch or two behind the ears). Wherever humans went, cats followed—and multiplied. A female cat can start reproducing at less than a year old and can have as many as three litters of five or more kittens each year for the rest of her life. It is not surprising, then, that people have been complaining about cat overpopulation for decades.

Over the past 10 years the science has made it clear that domestic cats are a conservation nightmare around the world. Because cats are found at population densities 10 to 100 times higher than those of similarly sized predators, their impact is far more profound than that of naturally occurring predators such as raptors, raccoons and snakes. They have been implicated as a major force in the extinction of 14 percent of bird, mammal and reptile species on islands. In 2013 Georgetown University conservation biologist Peter P. Marra and his colleagues at the Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that feral and outdoor cats kill about 2.4 billion birds every year—and that is on top of the estimated 12.3 billion rodents and other mammals also killed by cats. As free-ranging cats have been increasingly documented killing endangered wildlife, disputes such as the one in Key Largo have popped up around the world. Much less clear, however, is how to tackle the problem.

Historically, “cat control” meant rounding up and killing strays every now and then, often as a reactionary measure when things got out of hand. But given a cat’s extraordinary fertility rate, it did not take long for the feline population to get right back to where it started. Over the past few decades governments have tried an arsenal of more deliberate strategies, including poison sausages, sharpshooters, deadly viruses and a toxic gel sprayed on cats’ fur. Few of these tactics were practiced consistently over a long-enough period. Nearly all of them have failed, emboldening people who work in animal welfare to insist that simply killing cats is not just cruel but ineffective: today there are anywhere from 70 million to 100 million feral or unowned cats in the U.S. alone.

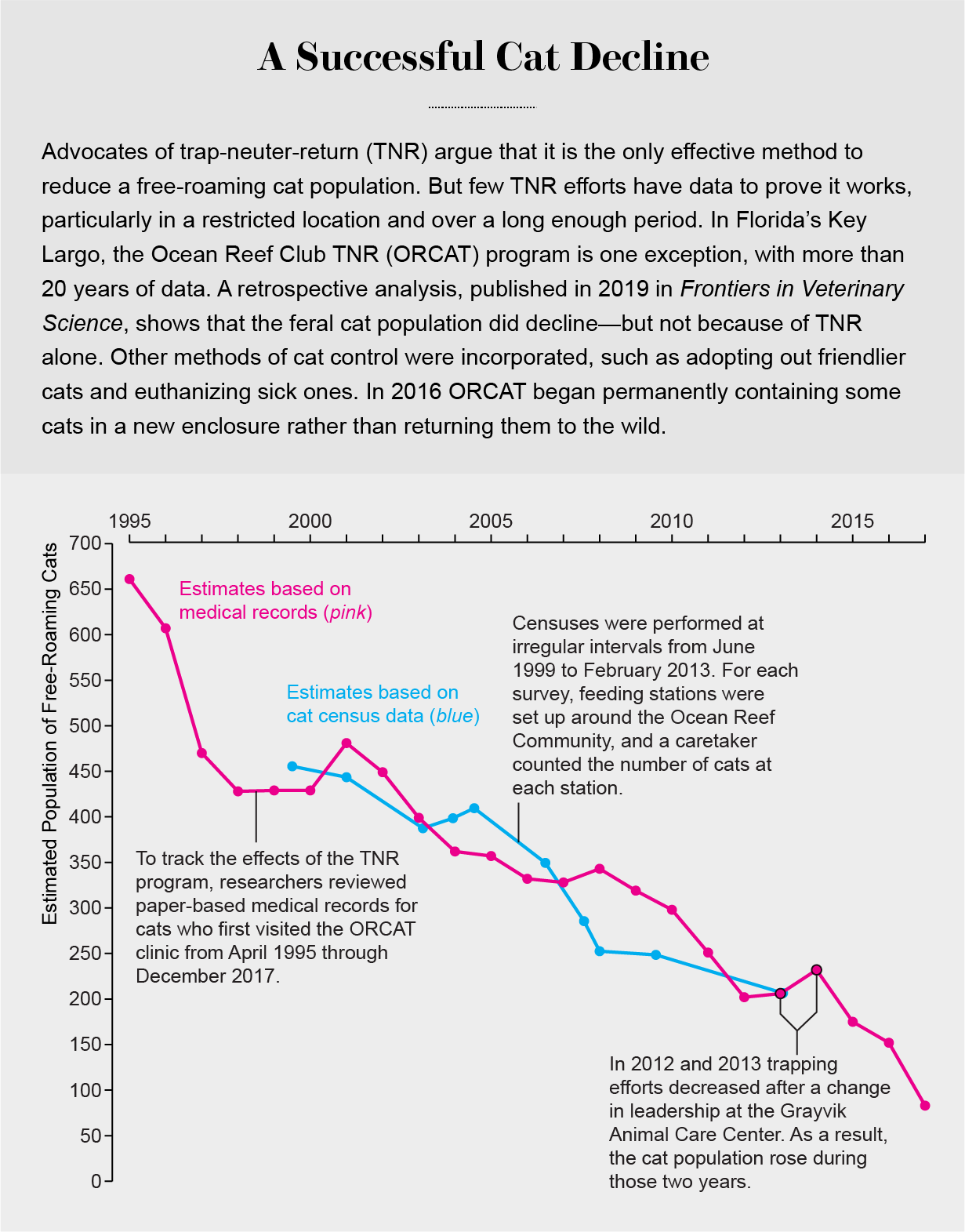

Instead cat supporters advocate for humanely trapping cats, sterilizing them and returning them to their colonies, or social groups, in the wild—a process known as trap-neuter-return, or TNR. If free-ranging cats are prevented from reproducing, feral cat colonies will naturally decrease in size over time as cats die. In the mid-1980s Julie Levy, who was then a veterinary student at the University of California, Davis, led one of the country’s first TNR efforts. Within a few years almost all the campus’s feral cats had been trapped and sterilized, and by the time Levy graduated the area around the veterinary school was nearly cat-free. “People were so excited to have an alternative solution,” she recalls.

In 1993 word of Levy’s California TNR project reached Alan Litman, a prolific inventor and a resident of the Ocean Reef Club. At the time thousands of feral cats roamed the property, which takes up one third of Key Largo. The occasional roundups for euthanasia, which did not sit well with many locals, were not working. Cat feces were everywhere, and owners filed a never-ending stream of complaints about the noise of cat fights and the smell of territory markings. Litman lobbied Ocean Reef to try TNR, and the club agreed, providing long-term funding to launch ORCAT with money from the homeowners’ association and private donations. Litman hired Susan Hershey, a technician at a local veterinary hospital, to head up the program. When she arrived in 1995, Hershey popped open a can of food on the street and encountered “70 or 80 cats, easily,” she recalls. “It was an extreme problem.”

Hershey spent most of the daylight hours baiting traps with cans of Friskies and waiting for unsuspecting cats to step inside. As the cats learned her routine and began to avoid the traps, Hershey constantly evolved her methods. Many of the cats she trapped were sick and had to be humanely euthanized; others were friendly and could be adopted into homes. Hundreds of cats, however, were healthy enough to be spayed or neutered but too fearful of humans for a life indoors. These cats were returned to their colonies with the top of their left ear removed to indicate that they were fixed. For five years Hershey and a growing team trapped and neutered practically around the clock. Slowly but surely, the number of cats at Ocean Reef began to drop.

The Negotiator

News of ORCAT’s success began to spread throughout the animal welfare community. Hershey became something of a TNR celebrity, fielding visitors from around the world who wanted to learn how to replicate the Key Largo program. The area’s feral cats also attracted biologist Michael Cove, then a young doctoral student at North Carolina State University, who arrived at the Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge in 2012. Although the number of cats at Ocean Reef had indeed declined, the woodrats were still in serious trouble, and Cove wanted to figure out how to better protect them. Feral cats often wandered into the refuge, lured by the industrious activities of the woodrats. Cove wanted to document the effects of cats on the woodrat population and understand how the cats—among other factors—limited woodrat recovery. To conservationists, the presence of ORCAT was anything but a victory.

Although a handful of studies from Rome to Rio de Janeiro have indeed shown persistent population reductions from TNR, it is not easy to sterilize enough cats to create a steady downward population trend, explains conservation biologist Grant Sizemore of the American Bird Conservancy. Modeling studies have shown that upward of 90 percent of the cats need to be fixed to create a steady population decline, and trapping that many cats is nearly impossible. Domestic cats reproduce so efficiently that even small gaps in cat colony maintenance can lead to a resurgence in numbers—something ORCAT’s own data show. Additionally, the presence of cared-for feral cats has been found to encourage people to dump their unwanted cats in the same area—which is often a reason the strategy fails. (It also helps to explain the success of ORCAT, which is located in a gated community on a small island.) “TNR is a Band-Aid solution for a gaping wound,” Sizemore says.

TNR supporters acknowledge that the method is imperfect. But Levy and Hershey argue that even with all its flaws, TNR is the only technique that has so far been shown to reduce cat populations over time. Humans have been killing cats for centuries, Levy says, yet millions of feral cats are currently living in the U.S. Marra disputes this logic, arguing that there is a difference between the occasional roundups of problem cats and newer efforts to strategically wipe cats out of an ecosystem. Modeling studies by Auburn University ecologist Christopher Lepczyk and others seem to support Marra’s point: under most circumstances, TNR is less effective at reducing cat populations than euthanizing the cats once they are trapped.

Both sides have accused the other of cherry-picking data to support its points. In 2018 Marra and other conservationists wrote an article calling TNR promoters “merchants of doubt,” the same term used for those who defend tobacco products and deny climate change for personal gain. But the underlying issue is that there are few data to start with, both on the scope of the problem (feral cats are difficult to count accurately, for instance) and on the best methods to reduce cat numbers in the context of bolstering wildlife. In that sense, the conservation cat fight has rested more on opinions than on evidence-based science. In a May 2019 article entitled “A Moral Panic over Cats” in Conservation Biology, ethicists, anthropologists and conservation biologists argued for seeing the gray areas.

Stepping into the morass, Cove knew that expelling cats from the refuge would require buy-in from ORCAT. He needed to show Hershey evidence that her cats were guilty as charged. No one had done fine-grained studies showing precisely how cats affected any species of endangered rodent, so that was where he started. Cove’s first results, later published as his Ph.D. dissertation, were damning: woodrat population density was inversely proportional to the number of feral cats on the landscape. If cats were around, woodrats generally were not, and any that were behaved differently than is typical.

On reviewing the results, Hershey bristled at the implication that she was part of the problem. After all, she had spent two decades working tirelessly to reduce cat numbers while no one at Crocodile Lake offered help. “I honestly didn’t know what more we could do,” she says. Cove switched tactics. He wanted to show that the population decline that comes with TNR is still too slow to save vulnerable species such as the woodrat. As Marra explains, “If you put a cat back in the environment, it’s going to keep killing.” When Cove analyzed cat fur found in the wildlife refuge, he learned that the cats almost exclusively ate food provided by humans, including commercial pet food and garbage scraps—only a small percentage consumed wildlife. But that did not stop them from hunting and killing woodrats.

Cove’s finding was supported by the work of University of Georgia ecologist Sonia Hernandez, who tracked the hunting habits of local cats on Georgia’s Jekyll Island in 2014 and 2015. Hernandez placed collar-mounted KittyCams on 31 feral cats that, like ORCAT’s, were fed daily. Evidence from the KittyCams showed that 18 of the cats were successful hunters, with an average of 6.15 kills a day. The cats, however, did not eat all of their prey. Cats hunt not because they are cruel or bloodthirsty, Marra explains, but simply because they are cats.

Ultimately Cove appealed to emotions. During his research, he had often set up motion-triggered cameras near woodrat nests to monitor cats in action. Cove captured several instances of cats climbing on the nests, proof that ORCAT’s animals were active in the refuge. In 2014 he got his money shot: a photograph of a cat with a limp woodrat in its mouth.

A cooperative effort

Cove’s footage helped to break through Hershey’s denial. Even if conservationists did not consider her work worthwhile, she had to admit the image was alarming. Many cat lovers have a similar response, explains Brooke Deak, a socioecology Ph.D. student at the University of Adelaide in Australia. She points to a 2013 study showing that Audubon Society members tend to view outdoor cats as invasive killers, whereas TNR practitioners see the same animals as the fluffy friends that share their homes.

Hershey had other incentives to rethink TNR as a panacea. Shortly after the failure of the woodrat-breeding program, officials at Crocodile Lake announced an invasive-species management plan that would, for the first time, empower them to trap and remove any cats found on the refuge. Some would be returned to Ocean Reef, and others would be delivered to animal control, where they could be reunited with owners, adopted, or humanely euthanized. The program was not just aimed at cats: it was also intended to manage invasive Burmese pythons, which had taken over the Everglades and prey on woodrats and cats alike. Reasonable as it might sound, cat lovers’ long-standing distrust of conservationists led them to worry that the plan amounted to a green light for indiscriminate killing of cats.

Fearing for the cats’ safety, an Ocean Reef resident donated $15,000 so that ORCAT could build a 500-square-foot indoor-outdoor enclosure to protect elderly, sick and otherwise vulnerable ferals. In 2016 the ORCAT team began setting traps not just to sterilize cats at Ocean Reef but also to keep them contained. Critically, Hershey acquiesced to Cove’s pleas that any of their cats found in the wildlife refuge be kept permanently in the new enclosure on return rather than being released back onto the property.

Cove, who is now a curator at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science, dislikes that TNR is still used at Ocean Reef: about 220 cats there roam free. “Feral cats should not be allowed within three miles of any natural area,” he says. But Cove grudgingly admits that Hershey’s recent efforts did reduce the number of feral cats even if they did not eliminate them. In work published in 2019 in Biological Conservation, Cove reported that as cats were permanently removed from Crocodile Lake through a multipronged approach, the woodrats’ distribution increased. The percentage of woodrat nest sites with active occupants in the refuge increased from 37 to 54 percent in just two years.

Cove’s study was small, but it was the first documented, scientifically rigorous attempt to control a feral cat population in the service of an endangered species. It provides evidence that it is necessary to remove cats permanently but that with community collaboration, it can be accomplished without the wholesale slaughter of cats. Now other groups are taking a data-centric approach. Projects in Washington, D.C., and in Portland, Ore., are seeking to provide an accurate count of outdoor cats, and a collaboration between Portland Audubon and the Feral Cat Coalition of Oregon is tracking the efficacy of cat-control methods on Hayden Island. The exact method of cat control will always be customized to each area, Deak says, but Cove’s work in Key Largo provides a blueprint.

Home Improvement

Although reducing feral cats’ incursions at Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge was an important first step, the woodrat population is still far from secure. Last November, Cove flew down from North Carolina to start prepping for a new series of studies. With no way to remove all free-roaming cats, regardless of the approach taken, Cove is investigating whether additional methods of human intervention could help protect the beleaguered rodent from cats and other invasive species.

Woodrats build giant nests by dragging thousands of sticks across yards of dense undergrowth. These structures—which can stand up to four feet high and stretch to more than eight feet across—serve as nursery, toilet, pantry and sanctuary. But the racket the woodrats create during construction can act as a homing beacon for nearby cats. In the mid-2000s DeGayner and his brother tried to solve this problem by providing the woodrats with artificial nests. If the brothers could not eliminate the cat threat, they could at least help mitigate some of its impact. They removed the innards of a discarded Jet Ski, repurposing the hull as a ready-made habitat. Woodrats moved in almost immediately, augmenting the structure with sticks over time. The brothers eagerly collected more watercraft.

Human assistance to endangered species is common in conservation. Cove wants to see how these faux châteaus affect woodrats’ chances of becoming a cat’s dinner. The study could provide valuable information to other conservationists who aim to protect vulnerable animal populations from feral cats.

On a cold November morning Cove and DeGayner cruised the two-lane highway that bisects Crocodile Lake, armed with a list of nest sites to check. First up was nest 427. The multigeneration woodrat home is just a few hundred yards from a busy road, but the site is hidden in a nearly impenetrable wall of green that swallows any traffic sounds. This family of woodrats built its home around the hull of a derelict Sea-Doo that the DeGayner brothers had dragged in more than a decade earlier. The woodrats decorated it with snail shells, Sharpie caps and bungee cords.

When Cove saw that the entrance to nest 427 had been swept clear of leaves and cobwebs—a clear sign that there were woodrats inside—he gave DeGayner a thumbs-up. “This one’s good,” he said. Over the next several hours the duo repeated this process upward of 20 times, sometimes celebrating signs of life, sometimes lamenting empty hulls. Crouching down in the shade just a few feet from the traffic rushing past on the highway, Cove pointed to a jumbled heap of sticks—a new nest he had not seen before. “It’s not much,” he said, “but it’s there.