Depression, anxiety and other psychiatric disorders can also influence physical health; they are linked with increased risk of heart disease, for example, and shorter life expectancy. Recent research suggests this may be related to accelerated aging—and new work finds that a form of purely psychological therapy can have a protective physiological effect.

A study led by clinical psychologist Kristoffer Månsson of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden showed that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), a common psychotherapy technique, not only reduced anxiety levels in people with social anxiety disorder but also improved cellular aging markers for some patients. This finding could ultimately help clinicians personalize treatments.

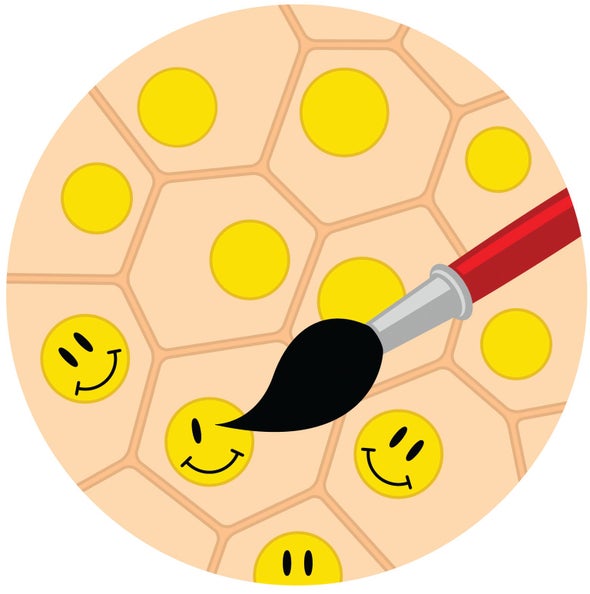

Telomeres, short DNA sequences that cap chromosomes' ends to protect them from damage, indicate cellular age. Each time a cell divides to drive growth and repair, its telomeres shorten. The enzyme telomerase maintains them to an extent, but eventually they shorten so much that cells can no longer divide, and signs of bodily aging appear. Telomeres also shorten through cellular damage caused by highly oxidizing molecules called free radicals.

Many studies link stress with shorter telomeres. And in 2015 researchers led by clinical psychologist Josine Verhoeven of Amsterdam University Medical Center found that patients with an active anxiety disorder had shorter telomeres than those in remission or healthy controls.

In the new study, published last December in Translational Psychiatry, the scientists first took two blood samples, nine weeks apart, from 46 people with social anxiety disorder. They measured the subjects' telomere length as well as levels of telomerase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), an antioxidant enzyme that counteracts free radical damage. The participants received nine weeks of online CBT and then gave another sample.

All measures remained largely unchanged over the two samples prior to therapy. But afterward, the subjects had increased GPx levels on average. Telomerase also rose among patients whose anxiety levels benefited most from treatment, although activity averaged over all participants did not change. There were even indications that telomerase activity could predict treatment response. “The people with the lowest telomerase had greater improvements,” says Verhoeven, who was not involved in the study. “This needs to be replicated, but it's an interesting lead for future research.”

A longer study might show changes to telomeres themselves; nine weeks was too short for that, according to Månsson. Nevertheless, the research suggests purely behavioral changes can affect health at a cellular level. “Our biology is remarkably dynamic,” Månsson says. “And it seems to respond quite quickly, over just weeks, with a behavioral intervention.”

“Psychiatry is very divided between the psychological and biological,” Verhoeven says. “This paper connects those fields.” These results could also help relieve the stigma of mental illness, she adds: “It's not something that's only in your head—it's also in your body.”