It is one of those facts of life that we learn early and don’t forget: normal body temperature is 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. But a new study in eLife argues that that number is outdated.

The figure was probably accurate in 1851, when German doctor Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich found it to be the average armpit temperature of 25,000 patients. Times have changed, though, according to the recent paper: the average American now seems to run more than a degree F lower.

Stanford University researchers looked at data from Civil War soldiers and veterans and two more recent cohorts to confirm that body temperatures among American men averaged around 98.6 degrees F back then but have steadily fallen over time and that temperatures among women have fallen as well. Their data find an average for men and women of 97.5 degrees F.

The study suggests that in the process of altering our surroundings, we have also altered ourselves, says senior author Julie Parsonnet of Stanford. “We’ve changed in height, weight—and we’re colder,” she says. “I don’t really know what [the new measurements] mean in terms of health, but they’re telling us something. They’re telling us that we are changing and that what we’ve done in the last 150 years has made us change in ways we haven’t before.”

The researchers did not determine the cause of the apparent temperature drop, but Parsonnet thinks it could be a combination of factors, including warmer clothing, indoor temperature controls, a more sedentary way of life and—perhaps most significantly—a decline in infectious diseases. She notes that people today are much less likely to have infections such as tuberculosis, syphilis or gum disease.

In places like the U.S., people also spend more time in what scientists call the thermoneutral zone—an environment of climate-controlled temperatures that make it unnecessary to rev up the metabolic system to stay warm or to cool off, she says. That perpetually 72-degree-F office may feel cold to some, but it does not stress out the human body the way it would to spend the night in a 40-degree-F cave. It is unclear whether those who live closer to the way people did in the 1800s—with more infection or less climate control—have higher body temperatures.

Research on the Tsimané, indigenous people who live in lowland Bolivia, suggests that infections can boost average body temperature. A 2016 paper showed that infections accounted for about 10 percent of resting metabolism in that population and that lower metabolism was associated with slightly lower body temperature, says Michael Gurven, an anthropologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who conducted that study but was not involved in the new one. Yet even in healthy members of the Tsimané population, temperatures appear to have dropped between 2004 and 2018, he adds—a phenomenon he plans to investigate further.

Parsonnet says she suspects it might be healthier to have a lower metabolism and body temperature. And she hopes to explore that connection more in the future.

For the eLife study, she and her colleagues compared temperatures from three different data sets: a total of 83,900 measurements from the Union Army Veterans of the Civil War (UAVCW) cohort, collected between 1862 and 1930; 15,301 measurements from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I (NHANES I), collected between 1971 and 1975; and 578,222 measurements from the Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (STRIDE), collected between 2007 and 2017. Figures for women were not available from the earliest data set but were collected from the two later cohorts, and the research showed that body temperature for men and women decreased steadily across the time periods.

Philip Mackowiak, an emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who was not involved in the new study, says data from as far back as the Civil War is inherently suspect. “That’s not to say that what [the new study] found is not valid. It could be, but you just don’t know,” he says, because there are so many variables that could not be controlled for in the data set, such as whether soldiers and veterans were healthy when tested, where the thermometer was placed and what kind of instrument was used.

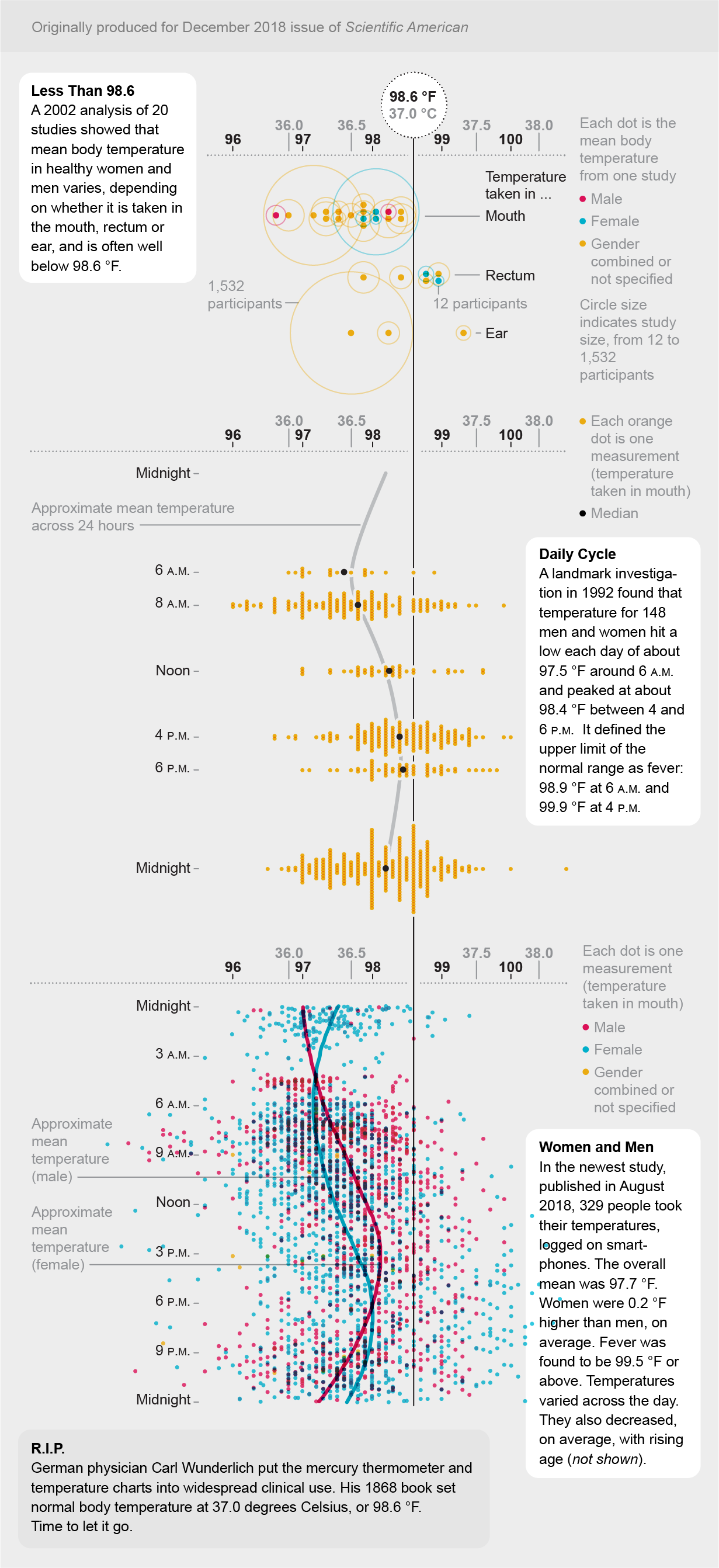

Even Wunderlich’s established 1851 result is questionable, Mackowiak says, because although he had a large database of patients, it is hard to know whether he measured temperature consistently or how he analyzed such a volume of information long before the invention of computers. And “the body is composed of a whole host of temperatures,” Mackowiak adds. The liver is the hottest part, and the surface of the skin is the coldest. Plus, he says, “there’s no ‘normal’ temperature; there’s a range of temperatures,” with people running hotter later in the day than they do in the morning. Women also have higher temperatures on average than men, in part because they rise with ovulation.

Parsonnet agrees that the Civil War data set has some limitations, such as where caregivers took the temperatures and whether they were careful or simply filled in 98.6 degrees F because that’s what they knew normal temperature was supposed to be. Those concerns were tempered, she says, by the fact that she and her team found a similar annual drop in temperature between the 1970s cohort and the current one. The effect was still present when examined by the soldiers’ and veterans’ year of birth rather than when the temperature was obtained, suggesting that the type of thermometer or the caregiver’s attitude could not explain the change. And within the data set, the researchers found the expected variation by age, weight and height, suggesting that the values were not random.

Even with the data’s limitations, the findings are compelling, according to Frank Rühli, founding chair and director of the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich, who says he reviewed the paper for eLife but was not involved in the research. “Human body temperature data going back that far—roughly 150 years—is very interesting,” he says. “It allows us to see short-term alterations of physiological traits in humans, which is quite rare.”

All the experts agree on one thing: a fever is still a fever. Lowering the average for normal body temperature does not mean that the standard for a fever—generally considered more than 100 degrees F for adults—should be changed, Mackowiak says. “Temperature can be helpful in determining whether or not you’re ill and, based on its level, how ill you might be,” he says. For patients, a bacterial infection plus a lower than normal temperature could be an even more ominous sign than a higher than normal one, he says. Following a rise or fall in temperature can also indicate whether you are getting better or how you are responding to medication, he adds, though “how you feel is the most important thing.”

The new study probably should not change the definition of fever, Rühli says. “But the variety of what is looked at as being normal should probably be adjusted.”