From the tallest peak in Hawaii to a high plateau in the Andes, some of the biggest telescopes on Earth will point towards a faint smudge of light over the next few weeks. The same patch of sky will draw the attention of Gennady Borisov, an amateur astronomer in Crimea, and many other hobbyists who will sacrifice proper sleep and doze through their day jobs rather than miss this golden opportunity.

What they’re looking for is a rare visitor that is about to make its closest approach to the Sun. After that, they have just months to grab as much information as they can from the object before it disappears forever into the blackness of space.

This chunk of rock and ice started its journey many light years from Earth, millions of years ago. The object got kicked out of its own neighbourhood by a violent gravitational push—maybe from a nearby planet, maybe from a passing star. Since then, it has been adrift in the space between the stars, eventually heading in our direction.

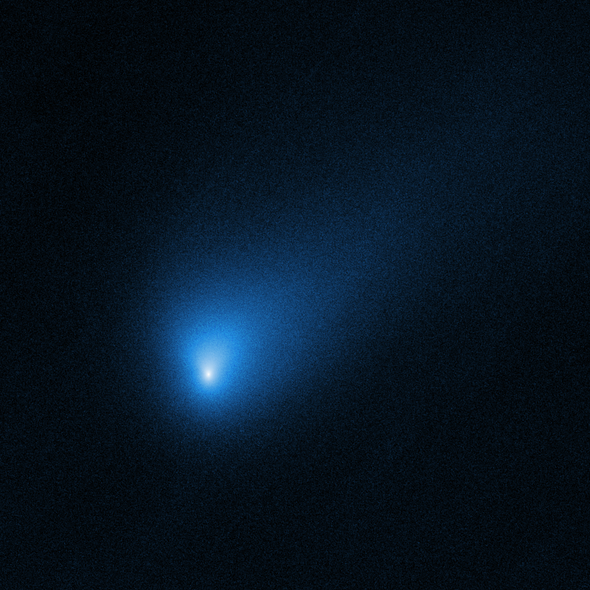

On 30 August, Borisov spotted the object in the predawn sky—it was glowing dimly, with a broad stubby tail. Later named Comet 2I/Borisov after its discoverer, it captured global attention because it’s only the second object—aside from exotic dust particles—ever known to have entered our Solar System from interstellar space. “This is my eighth comet, and so amazing,” says Borisov, who adds that it was “great luck that I got such a unique object”.

It is remarkably different from the first interstellar interloper, which was a small, dark, rocky-looking object named 1I/‘Oumuamua that whizzed past the Sun in 2017. Together, these two interstellar objects are rewriting what researchers know about the icy bodies—estimated to number as many as 1026—that float unmoored throughout the Milky Way.

Among other things, 1I/‘Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov have provided the first direct glimpse of the physics and chemistry of the squashed debris clouds that surround young stars and serve as the birthing grounds for planets. These samples from other planetary systems are allowing scientists to explore whether the Solar System is unique or whether it shares building blocks with other planetary systems in the Milky Way.

Because astronomers spotted 2I/Borisov on its way into the Solar System, they have many months to study it—unlike their fleeting glimpse of ‘Oumuamua, which was discovered on its way out. As a result, they expect to learn much more from 2I/Borisov, such as what chemical compounds make up its icy heart. It is their best look yet at an object known to have formed around another star.

And as telescopes continue to probe the sky for faint, fast-moving objects, researchers expect that they will spot many more interstellar interlopers in coming years. “It’s been so much fun to see this suddenly crack open and watch a new field develop,” says Michele Bannister, a planetary astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast, UK.

Dusty origins

Interstellar objects probably began their lives when icy grains clumped together in a disk of gas and dust around a young star. These are the same regions where planets grow from small nuclei and then ping-pong into different orbits around the star because of collisions and gravitational shoves.

The planets push through the icy rubble like a snowplough shouldering its way through a pile of hailstones. And modelling results suggest that the planets fling more than 90% of those ‘hailstones’ out of their star’s sphere of influence and into interstellar space. There they drift, as lonely scattered objects, until they happen to pass close enough to another star to be attracted by its gravity for a quick visit.

Astronomers had expected that the first interstellar object they saw would look like a typical comet. Most comets in the Solar System hail from the distant realm known as the Oort cloud, a sort of cosmic deep freeze that lies roughly 1,000 times farther away from the Sun than Pluto. Occasionally, something perturbs one of these comets and sends it careering towards the Sun; as it gets closer and warms up, its nucleus sprays out dust and gas that form a classic cometary tail.

But when the first interstellar visitor showed up, it didn’t look like a conventional comet. Unlike them, ‘Oumuamua was tiny—just 200 metres or so across—and rocky. Also, it was shaped like a cigar and tumbling end over end. That’s about all scientists could work out before ‘Oumuamua headed out of the Solar System.

By contrast, 2I/Borisov looks like an ordinary comet—and researchers are taking advantage of their time to study it. “We are keenly interested in seeing what the chemistry of this comet is, to see if it is different from those in the Solar System,” says Karen Meech, an astrobiologist at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu.

2I/Borisov is reddish in colour and is steadily spraying out dust particles. Its nucleus is relatively small, perhaps just one kilometre across, but that’s not unheard of for Solar System comets.

“After ‘Oumuamua, we had to completely revise what we thought interstellar objects might be like,” says Matthew Knight, a comet specialist at the University of Maryland in College Park. “But now the second one coming through looks more or less, so far, like what we thought we might see from a comet ejected from another star. Now I feel a lot better.” That suggests that the star systems where other worlds form might be much like our own.

The discoveries are coming fast. Just three weeks after 2I/Borisov was first seen, astronomers trained the 4.2-metre William Herschel Telescope in Spain’s Canary Islands on it and spotted molecules of cyanide gas streaming off the comet. It was the first-ever detection of gas from an alien visitor to the Solar System.

On 11 October, another research team used a 3.5-metre telescope in New Mexico to detect oxygen coming off the comet. The oxygen probably came from water breaking apart in the comet’s nucleus, making this the first time that researchers have spotted water from another star system entering our own. Together, the amounts of cyanide and water spraying from the comet aren’t surprising compared with what astronomers have seen from many other bodies.

Astronomers are watching keenly to see what other molecules, such as carbon monoxide, they can spot coming off 2I/Borisov as it gets closer to the Sun and warms up, which will further reveal how similar—or how different—it is to comets in the Solar System, says Maria Womack, an astronomer at the Florida Space Institute at the University of Central Florida in Orlando.

Early observations also suggest that 2I/Borisov might contain relatively low amounts of carbon-chain molecules such as C2 and C3. About 30% of the comets in the Solar System are similarly carbon-depleted. They typically come from relatively close to the Sun, rather than from the far reaches of the Oort cloud.

As months pass and astronomers gather more observations of 2I/Borisov, they hope to be able to understand much more about the planet-forming disk where it originated. “It’s going to be really exciting to figure out what the building blocks of other systems are going to look like relative to ours,” says Malena Rice, a graduate student in astronomy at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Researchers also hope to start unravelling how interstellar objects might have voyaged through deep space before showing up in the Solar System. Estimates suggest the objects experience many forces as they orbit the centre of the Galaxy, including occasional encounters with other stars or nudges from Galactic tides. Some scientists have tried to calculate which stars 1I/‘Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov could have formed around, but tracing their orbits back is difficult—like trying to reconstruct which bar a London pub-crawler started at from the final one they visited.

Other questions include when we can expect the next interstellar visitor, and how different it might be from 1I/‘Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov. Scientists didn’t expect two in such rapid succession after decades of fruitless searching. “I remain confused and astounded that the second object came along so fast,” says Robert Jedicke, an asteroid specialist at the University of Hawaii, who has worked to calculate the frequency of interstellar visitors. “They’re like buses,” says Alan Fitzsimmons, an astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast. “You wait decades for one to come along, and then two come along almost at once.”

Some astronomers are now poring through archival data to see whether objects spotted years ago were actually interstellar visitors that researchers did not recognize at the time. And the future rate of discovery is expected to rise—perhaps to one interstellar object a year—when the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope goes online in Chile in 2022, from where it will survey the entire visible sky every three nights. The European Space Agency has been working on a spacecraft concept, known as Comet Interceptor, that could visit future interstellar objects as they wing their way past the Sun.

Once astronomers have 10 or 20 interstellar objects under their belts, they should have a much better picture of what these deep-space wanderers are really like. “Eventually we’ll be talking about the Galaxy as something in which we are exchanging the products of planetary systems,” says Bannister. “It will be an entirely different way of doing astronomy.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on November 20, 2019.