In December 2003, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the first flight of the Wright brothers, the New York Times ran a story entitled “Staying Aloft; What Does Keep Them Up There?” The point of the piece was a simple question: What keeps planes in the air? To answer it, the Times turned to John D. Anderson, Jr., curator of aerodynamics at the National Air and Space Museum and author of several textbooks in the field.

What Anderson said, however, is that there is actually no agreement on what generates the aerodynamic force known as lift. “There is no simple one-liner answer to this,” he told the Times. People give different answers to the question, some with “religious fervor.” More than 15 years after that pronouncement, there are still different accounts of what generates lift, each with its own substantial rank of zealous defenders. At this point in the history of flight, this situation is slightly puzzling. After all, the natural processes of evolution, working mindlessly, at random and without any understanding of physics, solved the mechanical problem of aerodynamic lift for soaring birds eons ago. Why should it be so hard for scientists to explain what keeps birds, and airliners, up in the air?

Adding to the confusion is the fact that accounts of lift exist on two separate levels of abstraction: the technical and the nontechnical. They are complementary rather than contradictory, but they differ in their aims. One exists as a strictly mathematical theory, a realm in which the analysis medium consists of equations, symbols, computer simulations and numbers. There is little, if any, serious disagreement as to what the appropriate equations or their solutions are. The objective of technical mathematical theory is to make accurate predictions and to project results that are useful to aeronautical engineers engaged in the complex business of designing aircraft.

But by themselves, equations are not explanations, and neither are their solutions. There is a second, nontechnical level of analysis that is intended to provide us with a physical, commonsense explanation of lift. The objective of the nontechnical approach is to give us an intuitive understanding of the actual forces and factors that are at work in holding an airplane aloft. This approach exists not on the level of numbers and equations but rather on the level of concepts and principles that are familiar and intelligible to nonspecialists.

It is on this second, nontechnical level where the controversies lie. Two different theories are commonly proposed to explain lift, and advocates on both sides argue their viewpoints in articles, in books and online. The problem is that each of these two nontechnical theories is correct in itself. But neither produces a complete explanation of lift, one that provides a full accounting of all the basic forces, factors and physical conditions governing aerodynamic lift, with no issues left dangling, unexplained or unknown. Does such a theory even exist?

Two Competing Theories

By far the most popular explanation of lift is Bernoulli’s theorem, a principle identified by Swiss mathematician Daniel Bernoulli in his 1738 treatise, Hydrodynamica. Bernoulli came from a family of mathematicians. His father, Johann, made contributions to the calculus, and his Uncle Jakob coined the term “integral.” Many of Daniel Bernoulli’s contributions had to do with fluid flow: Air is a fluid, and the theorem associated with his name is commonly expressed in terms of fluid dynamics. Stated simply, Bernoulli’s law says that the pressure of a fluid decreases as its velocity increases, and vice versa.

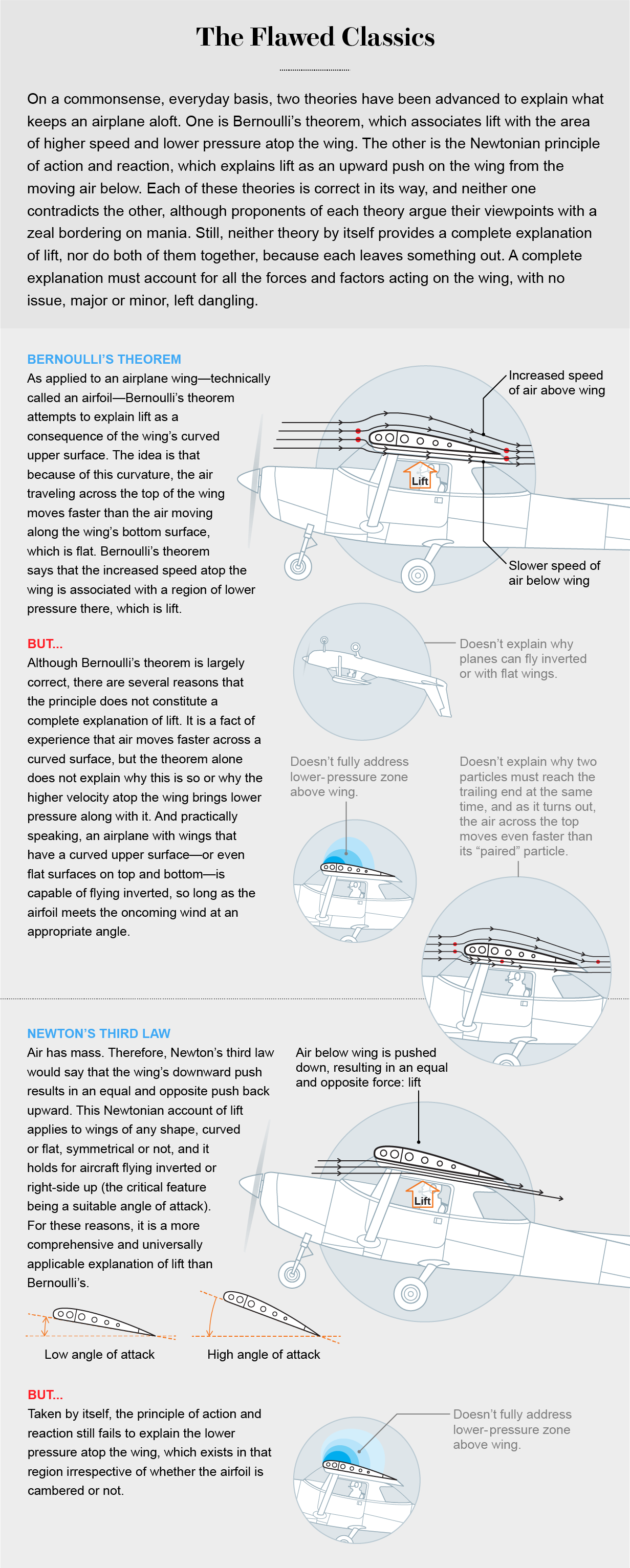

Bernoulli’s theorem attempts to explain lift as a consequence of the curved upper surface of an airfoil, the technical name for an airplane wing. Because of this curvature, the idea goes, air traveling across the top of the wing moves faster than the air moving along the wing’s bottom surface, which is flat. Bernoulli’s theorem says that the increased speed atop the wing is associated with a region of lower pressure there, which is lift.

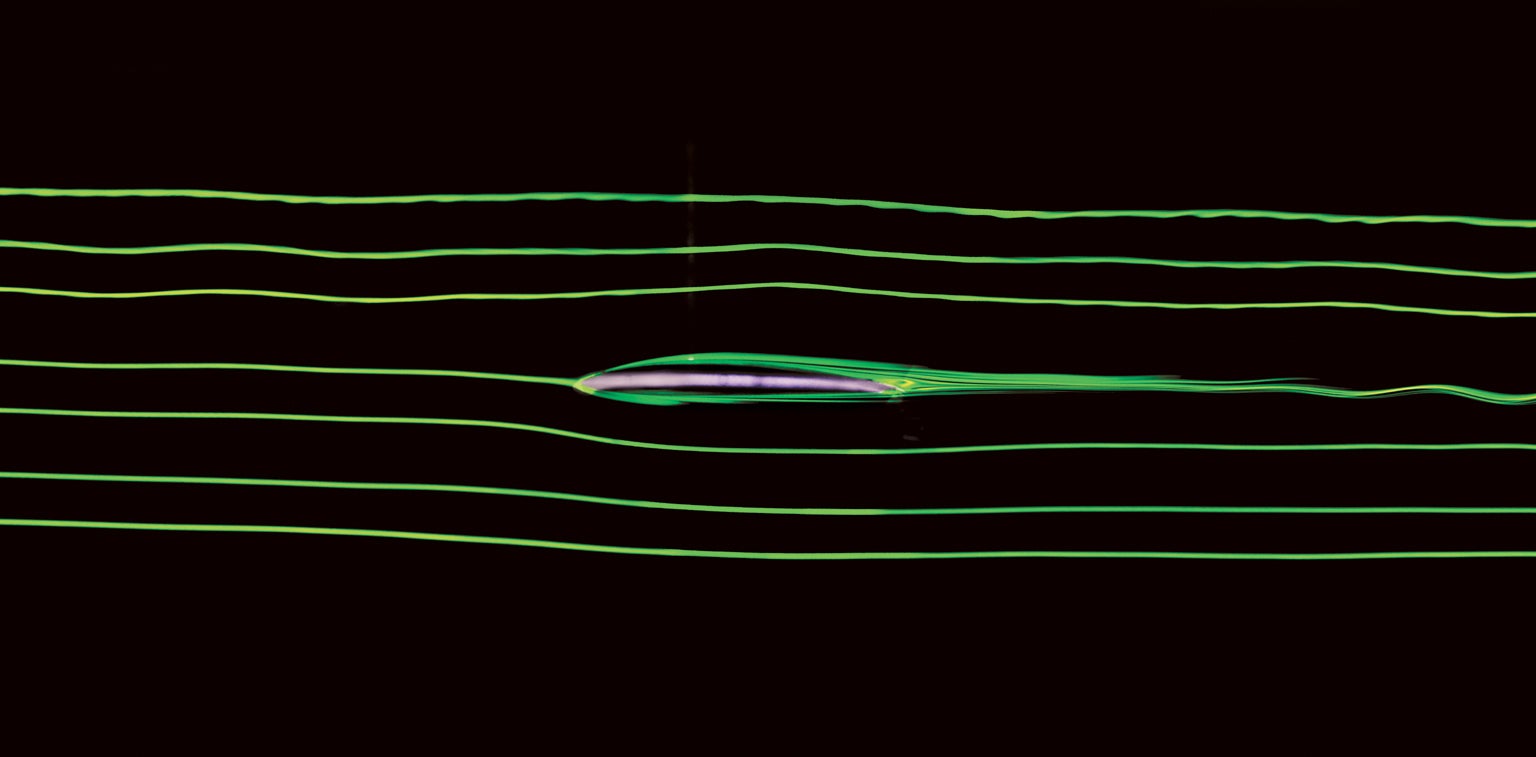

Mountains of empirical data from streamlines (lines of smoke particles) in wind-tunnel tests, laboratory experiments on nozzles and Venturi tubes, and so on provide overwhelming evidence that as stated, Bernoulli’s principle is correct and true. Nevertheless, there are several reasons that Bernoulli’s theorem does not by itself constitute a complete explanation of lift. Although it is a fact of experience that air moves faster across a curved surface, Bernoulli’s theorem alone does not explain why this is so. In other words, the theorem does not say how the higher velocity above the wing came about to begin with.

There are plenty of bad explanations for the higher velocity. According to the most common one—the “equal transit time” theory—parcels of air that separate at the wing’s leading edge must rejoin simultaneously at the trailing edge. Because the top parcel travels farther than the lower parcel in a given amount of time, it must go faster. The fallacy here is that there is no physical reason that the two parcels must reach the trailing edge simultaneously. And indeed, they do not: the empirical fact is that the air atop moves much faster than the equal transit time theory could account for.

There is also a notorious “demonstration” of Bernoulli’s principle, one that is repeated in many popular accounts, YouTube videos and even some textbooks. It involves holding a sheet of paper horizontally at your mouth and blowing across the curved top of it. The page rises, supposedly illustrating the Bernoulli effect. The opposite result ought to occur when you blow across the bottom of the sheet: the velocity of the moving air below it should pull the page downward. Instead, paradoxically, the page rises.

The lifting of the curved paper when flow is applied to one side “is not because air is moving at different speeds on the two sides,” says Holger Babinsky, a professor of aerodynamics at the University of Cambridge, in his article “How Do Wings Work?” To demonstrate this, blow across a straight piece of paper—for example, one held so that it hangs down vertically—and witness that the paper does not move one way or the other, because “the pressure on both sides of the paper is the same, despite the obvious difference in velocity.”

The second shortcoming of Bernoulli’s theorem is that it does not say how or why the higher velocity atop the wing brings lower pressure, rather than higher pressure, along with it. It might be natural to think that when a wing’s curvature displaces air upward, that air is compressed, resulting in increased pressure atop the wing. This kind of “bottleneck” typically slows things down in ordinary life rather than speeding them up. On a highway, when two or more lanes of traffic merge into one, the cars involved do not go faster; there is instead a mass slowdown and possibly even a traffic jam. Air molecules flowing atop a wing do not behave like that, but Bernoulli’s theorem does not say why not.

The third problem provides the most decisive argument against regarding Bernoulli’s theorem as a complete account of lift: An airplane with a curved upper surface is capable of flying inverted. In inverted flight, the curved wing surface becomes the bottom surface, and according to Bernoulli’s theorem, it then generates reduced pressure below the wing. That lower pressure, added to the force of gravity, should have the overall effect of pulling the plane downward rather than holding it up. Moreover, aircraft with symmetrical airfoils, with equal curvature on the top and bottom—or even with flat top and bottom surfaces—are also capable of flying inverted, so long as the airfoil meets the oncoming wind at an appropriate angle of attack. This means that Bernoulli’s theorem alone is insufficient to explain these facts.

The other theory of lift is based on Newton’s third law of motion, the principle of action and reaction. The theory states that a wing keeps an airplane up by pushing the air down. Air has mass, and from Newton’s third law it follows that the wing’s downward push results in an equal and opposite push back upward, which is lift. The Newtonian account applies to wings of any shape, curved or flat, symmetrical or not. It holds for aircraft flying inverted or right-side up. The forces at work are also familiar from ordinary experience—for example, when you stick your hand out of a moving car and tilt it upward, the air is deflected downward, and your hand rises. For these reasons, Newton’s third law is a more universal and comprehensive explanation of lift than Bernoulli’s theorem.

But taken by itself, the principle of action and reaction also fails to explain the lower pressure atop the wing, which exists in that region irrespective of whether the airfoil is cambered. It is only when an airplane lands and comes to a halt that the region of lower pressure atop the wing disappears, returns to ambient pressure, and becomes the same at both top and bottom. But as long as a plane is flying, that region of lower pressure is an inescapable element of aerodynamic lift, and it must be explained.

Historical Understanding

Neither Bernoulli nor Newton was consciously trying to explain what holds aircraft up, of course, because they lived long before the actual development of mechanical flight. Their respective laws and theories were merely repurposed once the Wright brothers flew, making it a serious and pressing business for scientists to understand aerodynamic lift.

Most of these theoretical accounts came from Europe. In the early years of the 20th century, several British scientists advanced technical, mathematical accounts of lift that treated air as a perfect fluid, meaning that it was incompressible and had zero viscosity. These were unrealistic assumptions but perhaps understandable ones for scientists faced with the new phenomenon of controlled, powered mechanical flight. These assumptions also made the underlying mathematics simpler and more straightforward than they otherwise would have been, but that simplicity came at a price: however successful the accounts of airfoils moving in ideal gases might be mathematically, they remained defective empirically.

In Germany, one of the scientists who applied themselves to the problem of lift was none other than Albert Einstein. In 1916 Einstein published a short piece in the journal Die Naturwissenschaften entitled “Elementary Theory of Water Waves and of Flight,” which sought to explain what accounted for the carrying capacity of the wings of flying machines and soaring birds. “There is a lot of obscurity surrounding these questions,” Einstein wrote. “Indeed, I must confess that I have never encountered a simple answer to them even in the specialist literature.”

Einstein then proceeded to give an explanation that assumed an incompressible, frictionless fluid—that is, an ideal fluid. Without mentioning Bernoulli by name, he gave an account that is consistent with Bernoulli’s principle by saying that fluid pressure is greater where its velocity is slower, and vice versa. To take advantage of these pressure differences, Einstein proposed an airfoil with a bulge on top such that the shape would increase airflow velocity above the bulge and thus decrease pressure there as well.

Einstein probably thought that his ideal-fluid analysis would apply equally well to real-world fluid flows. In 1917, on the basis of his theory, Einstein designed an airfoil that later came to be known as a cat’s-back wing because of its resemblance to the humped back of a stretching cat. He brought the design to aircraft manufacturer LVG (Luftverkehrsgesellschaft) in Berlin, which built a new flying machine around it. A test pilot reported that the craft waddled around in the air like “a pregnant duck.” Much later, in 1954, Einstein himself called his excursion into aeronautics a “youthful folly.” The individual who gave us radically new theories that penetrated both the smallest and the largest components of the universe nonetheless failed to make a positive contribution to the understanding of lift or to come up with a practical airfoil design.

Toward a Complete Theory of Lift

Contemporary scientific approaches to aircraft design are the province of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and the so-called Navier-Stokes equations, which take full account of the actual viscosity of real air. The solutions of those equations and the output of the CFD simulations yield pressure-distribution predictions, airflow patterns and quantitative results that are the basis for today’s highly advanced aircraft designs. Still, they do not by themselves give a physical, qualitative explanation of lift.

In recent years, however, leading aerodynamicist Doug McLean has attempted to go beyond sheer mathematical formalism and come to grips with the physical cause-and-effect relations that account for lift in all of its real-life manifestations. McLean, who spent most of his professional career as an engineer at Boeing Commercial Airplanes, where he specialized in CFD code development, published his new ideas in the 2012 text Understanding Aerodynamics: Arguing from the Real Physics.

Considering that the book runs to more than 500 pages of fairly dense technical analysis, it is surprising to see that it includes a section (7.3.3) entitled “A Basic Explanation of Lift on an Airfoil, Accessible to a Nontechnical Audience.” Producing these 16 pages was not easy for McLean, a master of the subject; indeed, it was “probably the hardest part of the book to write,” the author says. “It saw more revisions than I can count. I was never entirely happy with it.”

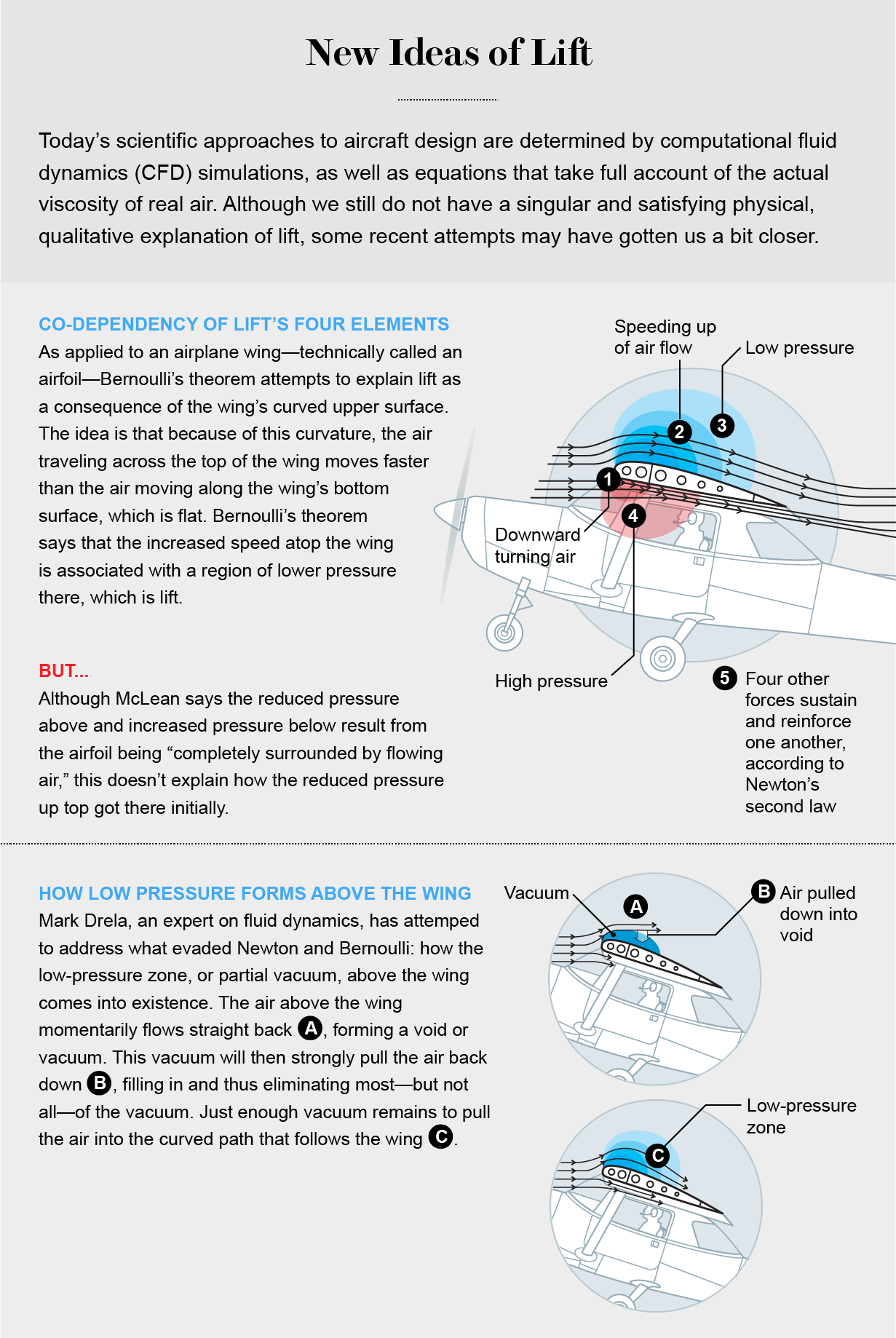

McLean’s complex explanation of lift starts with the basic assumption of all ordinary aerodynamics: the air around a wing acts as “a continuous material that deforms to follow the contours of the airfoil.” That deformation exists in the form of a deep swath of fluid flow both above and below the wing. “The airfoil affects the pressure over a wide area in what is called a pressure field,” McLean writes. “When lift is produced, a diffuse cloud of low pressure always forms above the airfoil, and a diffuse cloud of high pressure usually forms below. Where these clouds touch the airfoil they constitute the pressure difference that exerts lift on the airfoil.”

The wing pushes the air down, resulting in a downward turn of the airflow. The air above the wing is sped up in accordance with Bernoulli’s principle. In addition, there is an area of high pressure below the wing and a region of low pressure above. This means that there are four necessary components in McLean’s explanation of lift: a downward turning of the airflow, an increase in the airflow’s speed, an area of low pressure and an area of high pressure.

But it is the interrelation among these four elements that is the most novel and distinctive aspect of McLean’s account. “They support each other in a reciprocal cause-and-effect relationship, and none would exist without the others,” he writes. “The pressure differences exert the lift force on the airfoil, while the downward turning of the flow and the changes in flow speed sustain the pressure differences.” It is this interrelation that constitutes a fifth element of McLean’s explanation: the reciprocity among the other four. It is as if those four components collectively bring themselves into existence, and sustain themselves, by simultaneous acts of mutual creation and causation.

There seems to be a hint of magic in this synergy. The process that McLean describes seems akin to four active agents pulling up on one another’s bootstraps to keep themselves in the air collectively. Or, as he acknowledges, it is a case of “circular cause-and-effect.” How is it possible for each element of the interaction to sustain and reinforce all of the others? And what causes this mutual, reciprocal, dynamic interaction? McLean’s answer: Newton’s second law of motion.

Newton’s second law states that the acceleration of a body, or a parcel of fluid, is proportional to the force exerted on it. “Newton’s second law tells us that when a pressure difference imposes a net force on a fluid parcel, it must cause a change in the speed or direction (or both) of the parcel’s motion,” McLean explains. But reciprocally, the pressure difference depends on and exists because of the parcel’s acceleration.

Aren’t we getting something for nothing here? McLean says no: If the wing were at rest, no part of this cluster of mutually reinforcing activity would exist. But the fact that the wing is moving through the air, with each parcel affecting all of the others, brings these co-dependent elements into existence and sustains them throughout the flight.

Turning on the Reciprocity of Lift

Soon after the publication of Understanding Aerodynamics, McLean realized that he had not fully accounted for all the elements of aerodynamic lift, because he did not explain convincingly what causes the pressures on the wing to change from ambient. So, in November 2018, McLean published a two-part article in The Physics Teacher in which he proposed “a comprehensive physical explanation” of aerodynamic lift.

Although the article largely restates McLean’s earlier line of argument, it also attempts to add a better explanation of what causes the pressure field to be nonuniform and to assume the physical shape that it does. In particular, his new argument introduces a mutual interaction at the flow field level so that the nonuniform pressure field is a result of an applied force, the downward force exerted on the air by the airfoil.

Whether McLean’s section 7.3.3 and his follow-up article are successful in providing a complete and correct account of lift is open to interpretation and debate. There are reasons that it is difficult to produce a clear, simple and satisfactory account of aerodynamic lift. For one thing, fluid flows are more complex and harder to understand than the motions of solid objects, especially fluid flows that separate at the wing’s leading edge and are subject to different physical forces along the top and bottom. Some of the disputes regarding lift involve not the facts themselves but rather how those facts are to be interpreted, which may involve issues that are impossible to decide by experiment.

Nevertheless, there are at this point only a few outstanding matters that require explanation. Lift, as you will recall, is the result of the pressure differences between the top and bottom parts of an airfoil. We already have an acceptable explanation for what happens at the bottom part of an airfoil: the oncoming air pushes on the wing both vertically (producing lift) and horizontally (producing drag). The upward push exists in the form of higher pressure below the wing, and this higher pressure is a result of simple Newtonian action and reaction.

Things are quite different at the top of the wing, however. A region of lower pressure exists there that is also part of the aerodynamic lifting force. But if neither Bernoulli’s principle nor Newton’s third law explains it, what does? We know from streamlines that the air above the wing adheres closely to the downward curvature of the airfoil. But why must the parcels of air moving across the wing’s top surface follow its downward curvature? Why can’t they separate from it and fly straight back?

Mark Drela, a professor of fluid dynamics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of Flight Vehicle Aerodynamics, offers an answer: “If the parcels momentarily flew off tangent to the airfoil top surface, there would literally be a vacuum created below them,” he explains. “This vacuum would then suck down the parcels until they mostly fill in the vacuum, i.e., until they move tangent to the airfoil again. This is the physical mechanism which forces the parcels to move along the airfoil shape. A slight partial vacuum remains to maintain the parcels in a curved path.”

This drawing away or pulling down of those air parcels from their neighboring parcels above is what creates the area of lower pressure atop the wing. But another effect also accompanies this action: the higher airflow speed atop the wing. “The reduced pressure over a lifting wing also ‘pulls horizontally’ on air parcels as they approach from upstream, so they have a higher speed by the time they arrive above the wing,” Drela says. “So the increased speed above the lifting wing can be viewed as a side effect of the reduced pressure there.”

But as always, when it comes to explaining lift on a nontechnical level, another expert will have another answer. Cambridge aerodynamicist Babinsky says, “I hate to disagree with my esteemed colleague Mark Drela, but if the creation of a vacuum were the explanation, then it is hard to explain why sometimes the flow does nonetheless separate from the surface. But he is correct in everything else. The problem is that there is no quick and easy explanation.”

Drela himself concedes that his explanation is unsatisfactory in some ways. “One apparent problem is that there is no explanation that will be universally accepted,” he says. So where does that leave us? In effect, right where we started: with John D. Anderson, who stated, “There is no simple one-liner answer to this.”